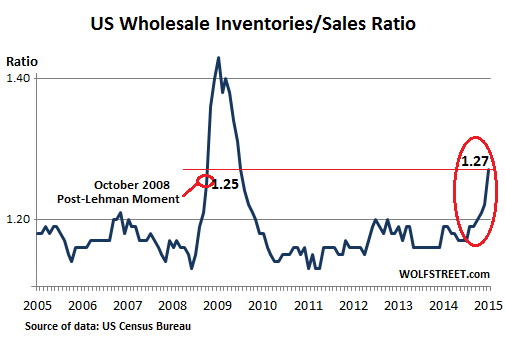

Wholesale inventories-sales ratio spikes worse than in Oct. 2008

A month ago, when I last wrote about it, I half-figured, half-hoped that the lousy wholesale inventories and sales for December had been a fluke, that some numbers had gotten lost in the shuffle, that the trend would reverse in January. Now the January data is out. And it’s terrible.

This time, there weren’t any redeeming qualities left.

Inventories tie up cash. So inventory management has become a sophisticated obsession, tightly connected to sales forecasting. Merchants who are optimistic about sales prospects stock up for it. When these hopes turn into crummy sales, inventories begin to balloon, and the crucial inventories-sales ratio rises to ugly levels.

And for January, that ratio has spiked to a level worse than October 2008, after Lehman had collapsed. That ratio is not some kind of semi-irrelevant financial indicator; it’s a red flag for the real, main-street economy.

The problem: hopes turned into terrible sales. January sales by merchant wholesalers (except manufacturers), adjusted seasonally but not for price changes, fell 3.1% from December to $433.7 billion, the Census Bureau reported today. Even year-over-year, wholesales fell 1.0%!

On a monthly basis, there were only four categories with sales gains: automotive +2.5%, professional equipment +0.6%, computer equipment +1.3%, and paper +1.2%. That was it. For the rest, sales were relentlessly negative. The biggest losers: petroleum products -13.5%, electrical -4.4%, metals -4.1% miscellaneous nondurables -4.2%. Even drug sales – the second largest non-durable category behind groceries but ahead of petroleum – dropped 3.6%!

But wholesale inventories rose to $548.7 billion at the end of January, up 0.3% from December, and up 6.2% from January a year ago. Year-over-year, durable goods inventories jumped 7.7%; nondurable goods inventories 3.7%.

Only three categories showed year-over-year declines in inventories: petroleum products, such as gasoline held by wholesalers, plunged 20.8%, and farm products fell 5.9%, after sharp declines in commodity prices; misc. durable goods inventories fell 3.0%.

All remaining inventory categories rose year-over-year. Among the standouts: automotive inventories jumped 8.7%, furniture 7.0%, lumber 4.1%, professional equipment 9.7%, computers 12.2%, metals 13.1%, electrical equipment 10.2%, hardware 13.5%, drugs 18.4%. You get the idea.

Given lousy sales and rising inventories, the inventories-sales ratio has been ticking up since July last year, when it was 1.17. It hit 1.22 in December, above the level of September 2008, the Lehman Moment. In January, it popped to 1.27. Now we’re looking at a spike:

Sure, the ratio had been higher back in the day. In the 1970s and 1980s, computerized inventory management and ordering systems were driving the trusty index-card systems into extinction. Each innovation along the way improved inventory management and allowed businesses to keep lower stocks while improving sales. Hence, over the decades, the wholesale inventories-sales ratio steadily declined to reach 1.14 in October 2005, which it revisited in 2010. In early 2011, it dropped to 1.13.

So what we should see is a continued slow and halting decline of the inventories-sales ratio. But since 2013, and particularly since July 2014, we’ve been seeing the opposite. And wholesale merchants aren’t seeing that rosy scenario of rising sales and declining inventories either.

Businesses across the US, each struggling to run a lean operation, will try to get their inventories in line. If a miracle happens and sales suddenly take off, halleluiah, problem fixed. If that strategy doesn’t work, they’ll trim their orders. And those orders are the sales of their suppliers.

When businesses across the country cut orders enough, they contribute to a chain of events that may trigger a business cycle recession. After Lehman collapsed, businesses cut orders so drastically that the supply chain seized. Sales throughout the economy were spiraling down. Inventories were soaring. The inventories-sales ratio went ballistic. And stocks crashed.

So the sudden Lehman-Moment-like spike in the ratio is disconcerting.

Businesses will eventually react. Maybe they’re still blaming the weather, and they’ve got big plans for promos, and optimism for the next few months is swapping over the brim. But if that miracle on the sales side doesn’t happen soon, the scenario might take on ugly hues. And it would happen just when stocks and bonds are at ludicrously inflated levels, precariously teetering, waiting for just such an event.

The financial scenario that corporations have been feverishly preparing for over the past few years took another step forward. Read… A “Crush” of Bond Sales Before the Market Goes to Heck