It is easy to make jokes about the BEA’s newfound respect for “residual seasonality” that in the words of CNBC’s chief economist makes each Q1 appear to be a “different economy altogether”, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something to it if in a far different manner than the mainstream would ever contemplate. There clearly is and has been for at least the past two or even three years a confusing set of circumstances that have repeated. Each year starts out very slowly only to seemingly rebound, but with each rebound being far more “transitory” than the actual weakness that preceded it. The result is almost a ratchet effect, where the media and economists over-emphasize each bounce that “somehow” leads only to the next bout of weakness at an even lower condition.

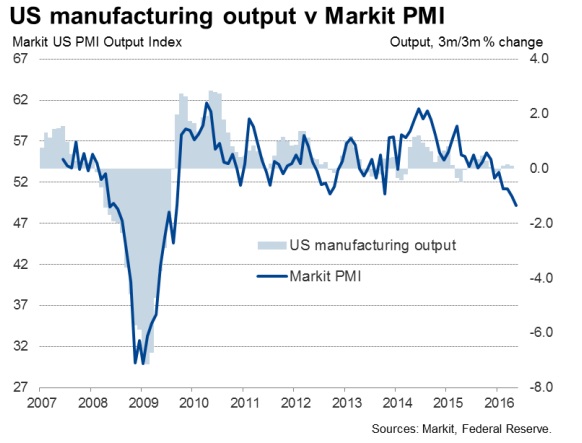

It started in 2014 during the Polar Vortex but really took shape last year after the sudden and dizzying drop in so many economic accounts; especially those related to manufacturing and the distribution of global goods. The Markit Manufacturing PMI ended 2014 on a major downswing, with the index having rebounded from the “cold” winter to start that year before jumping to nearly 58 by mid-year. It started 2015 at about 54 before again rebounding to almost 56 in February and March. Given that Fed Chair Janet Yellen declared all weakness, as oil prices and “inflation”, transitory, it was enough for everyone to suddenly see it that way, too; including Markit (from March 24, 2015):

Manufacturing new order levels increased at a robust and accelerated pace in March, driven by improving economic conditions and positive overall spending patterns among clients. The latest rise in incoming new work was the fastest for five months, but still less marked than the average for 2014 as a whole.

That one statement provided all that was necessary to figure the US economy, but the mainstream focused on the five-month high in orders while totally excluding how that high was suddenly lower than the prior year average. Chief Economist Chris Williamson remarked:

Manufacturing regained further momentum from the slowdown seen at the turn of the year, with output, new orders and employment growth all accelerating in March.

While economic growth looks set to disappoint again in the first quarter, with GDP set to rise by a rate perhaps slightly below the 2.2% expansion seen in the fourth quarter of last year, the upturn in order books in particular gives some reassurance that the pace of economic growth is likely to pick up as we move towards the summer.

Of course, the pace of economic growth did not pick up. Instead, the economy in the US and everywhere else followed the “global turmoil” in financial markets that amount to the immediate and relative fussiness of eurodollar and global liquidity conditions. Thus, the rebound past January 2015 was only the relenting of further direct funding pressure flowing into economic sentiment (PMI’s are surveys of business sentiment). What the PMI’s were suggesting of that rebound was therefore quite minimal in only that February and March 2015 were relatively better than January 2015, but not altogether different.

The pattern repeated again to start 2016 in many accounts. From the ISM PMI to certain data measures, we found a relative improvement that has since been unraveling as nothing more than the same replayed hopes of last year. Once again it suggests February and March 2016 were only better than this January, which doesn’t actually amount to a meaningful difference. The Markit PMI, perhaps significantly, didn’t even register that “improvement.” Instead, this view of the manufacturing economy has been consistently slowing really since last March. It had been consistently more optimistic about the state of manufacturing than other indications, maybe signifying a higher degree of seriousness about it this year compared to last.

The flash reading for May was just 50.5, with the production subindex below 50 for the first time since 2009.

Disappointing flash manufacturing PMI data cast doubt on the ability of the US economy to rebound from its weak start to the year. The seasonally adjusted Markit Flash US Manufacturing PMI™ sank to 50.5 in May, down from 50.8 in April, its lowest since September 2009.

Producers reported the first, albeit only marginal, reduction in output since September 2009 in May. Uncertainty around the general economic outlook had reportedly caused clients to delay spending decisions, leading to the weakest rise in new orders seen in 2016 so far. New export sales fell for the second month in a row.

Backlogs of work were meanwhile found to have dropped at the joint-fastest rate since the recession, meaning firms will be poised to cut capacity unless inflows of new work start to pick up again.

These updated survey results are not likely to indicate a services-led rebound, either. As Markit’s US Services PMI reported earlier in the month (for April 2016), manufacturing weakness does indeed appear to be hitting the service sector particularly in the broad-based exposure of services to the so-called goods economy:

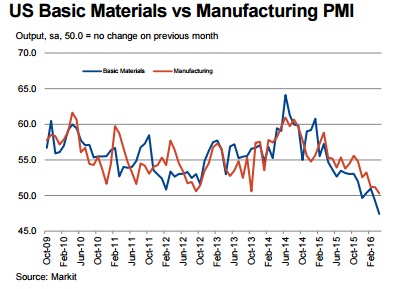

The latest release of US Sector PMI® data from Markit indicated that manufacturers had underperformed in April. In line with a near stagnation in overall manufacturing production, basic materials and consumer goods were two of the three worst-performing sectors in April.

Basic materials output fell at the sharpest rate in the survey’s history, while consumer goods production rose at the slowest pace in two-and-a-half years. Basic materials was bottom-ranked out of the seven monitored sectors, as was the case on average in 2015. The fall in production was driven by a solid decline in new work. Job losses were also reported, thereby ending a 77-month period of workforce growth.

Because we are presented in the mainstream essentially a binary choice between recession and not recession, anything that isn’t directly and immediately recognizable as recession is claimed as the opposite choice by default. What is, or really should be, clear by now is that there aren’t only two economic states. This one is worse than recession, as the economy takes months and now years under slow decay where, if going solely by mainstream accounts, you don’t even realize what has happened. Rebounds are extrapolated extravagantly consistent with downplaying anything that suggests a sustained if uneven downward direction even though, at the end of it all at whatever current month, that is all the economy seems to be able produce. The media only writes or talks of an economy that appears to be getting better from a worse start every time.

Markit’s PMI, like all of the rest of them, is only useful in relative fashion. This time, it didn’t even get better after what was truly a rough beginning no matter what absolute number is printed on each release. In August 2014 just as the “rising dollar” really got started, it was 57.9. Thus, the most important implication of May 2016’s 50.5 is not that it is barely “growing” or that it hasn’t employed a direct line to that reading, but rather that it is now a great deal less than 58 taking nearly two years to become so. That’s multiple years of weakness and doubt, with only growing suspicion as to actual recession.