They’re supposed to save the Eurozone, but the sanctions spiral against Russia and a whiff of reality take their toll.

They’re supposed to save the Eurozone, but the sanctions spiral against Russia and a whiff of reality take their toll.

Germany is expected to pull the Eurozone out of its funk by stimulating internal consumption. It is expected to allow the ECB to print money and stir up inflation so that other Eurozone countries like Spain or France can leverage that inflation to cut real wages, impoverish their people, devalue mountains of debt, make exports cheaper, and push imports beyond the reach of the poor.

The Eurozone is mired down, and it’s holding back the global economy. Germany would have to do its job. Not German exporters, for crying out loud – they’re causing all the problems, the official thinking goes. But German consumers, the same ones whose dour mood can last for years. They’d have to pull the Eurozone, and by extension the global economy, out of their funk.

But those consumers are getting cold feet, after businesses and investors have gotten cold feet months ago.

The Ifo Business Climate Index fell to its lowest level since April 2013. Business Expectations fell to their lowest level since December 2012. In manufacturing, expectations dropped into the negative for the first time since January 2013, dragged down by flagging exports. Construction hit the lowest level since December 2012, and wholesaling hit the lowest level since March 2010. The Ifo Employment Barometer backed off as well. The German economy is sputtering.

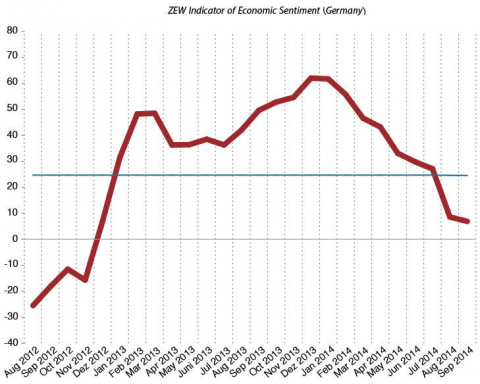

The sentiment of “financial experts” has been diving for nine months in a row. The ZEW Indicator, whose the long-run average is 24.6, now sits at 6.9, the worst level since December 2012, when markets were climbing out of the debt crisis debacle (ugly chart). The report blamed the “sanction spiral with Russia” and “disappointing” economic activity in the Eurozone.

For months, German consumers had been blissfully oblivious to the fretting by businesses and financial experts. “Extremely optimistic economic outlook,” is how GfK, which conducts the monthly consumer survey, described it at the time. But now, for the second month in a row, their mood soured. In the forward-looking GfK survey, the overall index fell to 8.3 for October, from 8.6 in September and from 8.9 in August – after a spectacular uninterrupted rise going back to January 2013. So on the surface, they’re still feeling pretty good.

But beneath the surface, oh my!

In late 2007, another one of those rare periods when Germans were feeling high, the index had hovered above 9. A year later, during the financial crisis, the index plunged below 2. And it took until early 2014, to get it back above 8.

Then last month, GfK reported that the sub-index for economic expectations, “in light of the intensified state of international affairs, completely collapses.” It had plunged over 35 points to 10.4, the worst plunge since the beginning of the survey in 1980. GfK cited the escalation of unrest around the world, particularly in Ukraine, and “the faster rotating sanctions spiral with Russia,” which have hit exports and could become “a real danger for the German economy.”

After that historic plunge last month, you’d expect some sort of bounce. Things don’t deteriorate that fast. It must have been an overreaction. Not even the financial crisis had come close. Or maybe it was a statistical fluke. At least, you’d expect a dead-cat bounce.

But heck no. Consumers’ economic outlook dropped again, this time by six points to 4.4, the lowest level since July 2013. GfK explained the phenomenon this way:

Consumers feel that the ongoing tense geopolitical situation and the economic weakness in a number of Eurozone countries will have a greater impact on the German economy. The economic development is showing the first signs of skid marks.

In Q2, GDP fell 0.2%. In Q3, the economy is expected to stagnate or, according to wishful thinkers, improve slightly. Consumers rode through the Q2 debacle without pause, but now they’re worried.

In the wake of swooning economic expectations, income expectations, after hitting an all-time record high in August, fell 4.6 points for September and 6.7 points for October to 43.3. The “continued high level,” as GfK called it, was a reflection of the “stable” labor market and the fact that “real income is rising as a result of very low inflation. These are decisive pillars for income expectations.”

The all-important phrase in Germany: “real income is rising as a result of very low inflation.” Very low inflation is keeping income expectations from heading south even faster! More on that in a moment.

The willingness-to-buy indicator dropped 6.8 points to 42.4, now below the level of a year ago, beaten down by plunging economic expectations and deteriorating income expectations. Last month, GfK called the level “relatively robust.” Now it’s less so, but it is still propped up by rising real wages, low inflation, and low interest rates. For the moment, consumers are still “more inclined to consumer rather than save their money.”

Someone should tell ECB President Mario Draghi and inflation mongers in the French government and elsewhere what German consumers, on whom the salvation of the Eurozone apparently depends, will do with their wallets when they see inflation eating into their wages and scarce savings. They’ll close that wallet! And they’ll go on one of their infamous buyer strikes that can last for years.

GfK blames the international crises that are “slowing down the consumer climate.” Consumers are already showing “the signs of uncertainty.” And there is “a danger that private consumption could no longer play its role as an important pillar of the economy.”

And that would be the final nail. Investor sentiment has been tanking for nine months. The business climate has been deteriorating for six months. GDP in Q2 fell. Q3 doesn’t look promising. And this is the vaunted economy whose consumers are supposed to pull the Eurozone, and by extension the global economy, out of its funk. Prost!

And now a true debacle is unfolding, just when we thought the euro was finally safe. Read…. Standard & Poor’s Warns on Germany Triggering the Next Debt Crisis, Investors Would Lose their Shirts