By Nicole Freidman at The Wall Street Journal

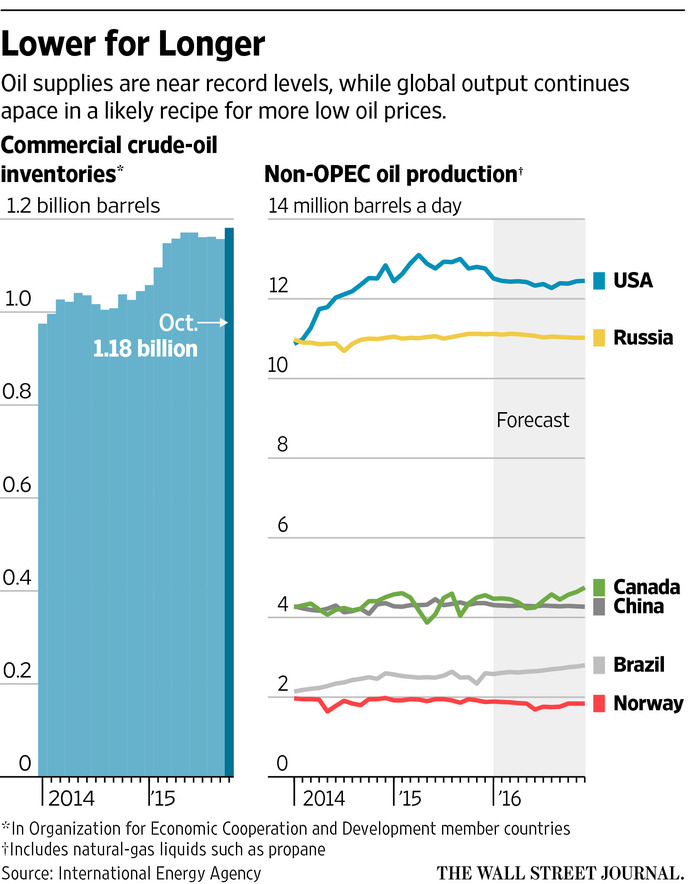

Surprisingly strong crude output in the U.S. and Mideast over the past year pushed oil prices to their lowest levels in more than a decade. But for investors trying to determine whether the oil market is close to a bottom, the pace of production elsewhere in the world is a key source of uncertainty.

Producers in Russia, Brazil and Norway pumped more oil in 2015 than the closely watched forecasters International Energy Agency and Energy Information Administration had projected. Meanwhile, oil-field investments made years ago when prices were higher are set to begin producing, even as exploration-and-drilling projects scheduled to bear fruit in the coming decades are being delayed or canceled outright.

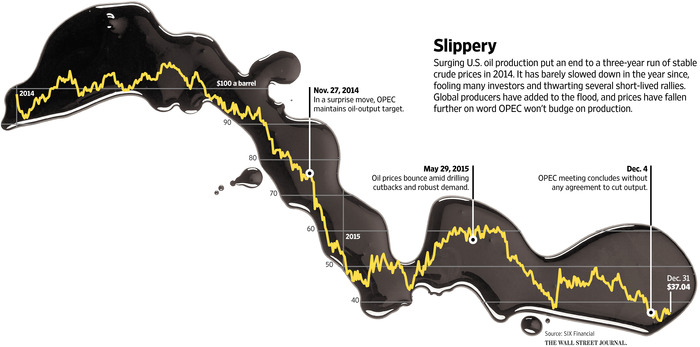

Investors’ increased focus on supplies from outside the U.S. and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries underlines uncertainty about the magnitude of a global oil glut that has erased more than 60% off the value of a barrel of oil in the past 18 months.

On the one hand, analysts say, low oil prices can cause oil wells to deplete more quickly, because companies spend less to maintain fields and enhance production from aging wells. On the other hand, producers have surprised investors in the past year with their ability to increase drilling efficiency and cut costs.

Given the strength of production around the world in 2015, many investors say it is far from clear when the glut will start to recede, given that OPEC hasn’t stepped in as it has in past downturns to stabilize the market by cutting output and U.S. production remains resilient.

“We’re in untested waters,” said Judith Dwarkin, chief economist at RS Energy Group. “This is an oil market that…since commercial trading began, has either been under the sway of monopolies, oligopolies or a cartel.”

Without coordinated supply cuts, economists say, it is in each producer’s best interest to pump as much as possible during a price downturn to maximize revenues.

“It is not the role of Saudi Arabia, or certain other OPEC nations, to subsidize higher cost producers by ceding market share,” said Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, in a speech in March.

U.S. oil prices have averaged $48.86 a barrel this year through Tuesday, compared with an average price of $95.05 a barrel between 2011 and 2014. Brent, the global benchmark, cost $53.79 a barrel on average this year, compared with $107.69 a barrel in the four prior years.

The U.S. oil benchmark gained $1.06 a barrel, or 2.9%, to $37.87 a barrel Monday on the New York Mercantile Exchange, down 29% on the year.

Global oil production increased by 2.28 million barrels a day, or 2.4%, in 2015, according to the EIA. OPEC and the U.S. account for most of the growth, but the rest has come from Brazil, China, Canada, Russia and elsewhere. The EIA expects global output to grow by 250,000 barrels a day, or 0.3%, in 2016.

Robust non-OPEC production outside the U.S. has confounded analysts and investors who thought those nations’ output would quickly decline as prices fell.

“The idea that OPEC and the other large oil producers like Russia would reduce output at these lower prices is misguided,” said John Brynjolfsson, chief investment officer of Armored Wolf, which manages money as part of a family office. “For a couple of years to come, output will exceed demand.”

Some money managers disagree. Bullish investors believe that non-OPEC supply could fall sharply in 2016, spurring a rebound in prices by year-end. Large producers faced pressure to cut spending even before oil prices plunged, and the pace of spending cuts accelerated in 2015. Producers delayed or canceled about 13 million barrels a day worth of oil output in the past five years, equal to about 14% of current global production, including 5 million barrels a day that would have been produced by 2020 deferred due to low prices, according to energy-focused investment bank Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co.

“Demand is growing and supply is reducing,” said Tim Guinness, chief investment officer of Guinness Atkinson Asset Management Inc., which manages $300 million in energy-equity investments. Mr. Guinness said he expects to see Brent oil prices at $75 a barrel by the end of 2016. “The world was out of balance. It’s now coming back into balance.”

Oil projects can take years to develop, so the market won’t feel the effect of spending cuts until 2017 at the earliest, other analysts say.

For 2016 production, “the investments have been made, the wells have been drilled,” saidJulius Walker, senior consultant at JBC Energy in Vienna. JBC doesn’t expect spending cuts made in 2015 to have much effect on output in 2016 in non-OPEC countries besides the U.S. In the U.S., where shale-oil drilling can be started and stopped relatively quickly, JBC expects 2015’s spending cuts to lead to a decline in production in 2016.

U.S. production fell from 9.6 million barrels a day in April 2015, a 43-year peak, to 9.2 million barrels a day in November, according to EIA estimates. The decline has been slower than many expected at the beginning of the year. The EIA predicts U.S. output will fall to 8.5 million barrels a day in September 2016 before increasing again.

In addition, ample global inventories of crude oil and refined products are expected to keep prices subdued next year. Stockpiles have climbed to record levels in recent months, sparking concerns that storage capacity could run out in some regions.

Oil investors have been humbled in the past year as their initial expectation that U.S. shale-oil production would quickly decline was proved wrong. Analysts said in 2014 that shale-oil output would drop sharply if prices fell below $80 a barrel, but producers got more efficient and cut costs. Some companies now say they can increase production if prices rise above $60 a barrel.

Those same efficiency gains have helped producers around the world. Goldman Sachs analysts expect production growth in 2016 in the Gulf of Mexico, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Russia and the North Sea.

“The experience in the shale sector is a little bit of a cautionary tale,” said Bo Christensen,head of macro and tactical asset allocation at Danske Invest in Copenhagen, which manages about $100 billion. “Anybody who wants to call themselves an expert and say, ‘Non-OPEC conventional [producers], they can’t possibly increase production further,’ [should] go back two years and think about what so-called experts told us about shale oil.”

Source: Not Even OPEC Can Fix Oil Glut – The Wall Street Journal