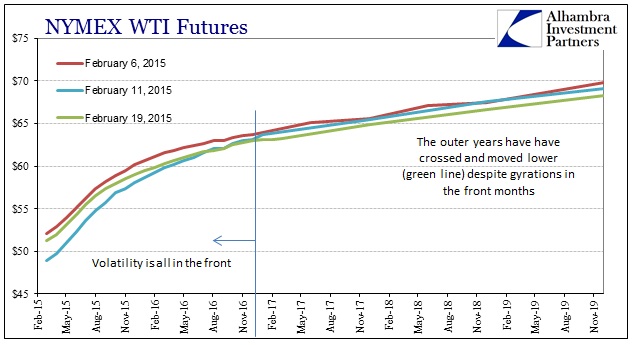

Crude oil futures have been quite volatile of late, particularly in the front months where even the slightest changes in expectations of whatever factor (rig counts, CEO comments, etc.) send WTI surging or tumbling by turn. Despite that, however, the outer years on the curve have seen not just more stability but a steady downward pressure of late. I think a lot of that has to do with futures investors reconciling actual contango options with the idea that demand is far more of not just a problem, but a longer-term problem.

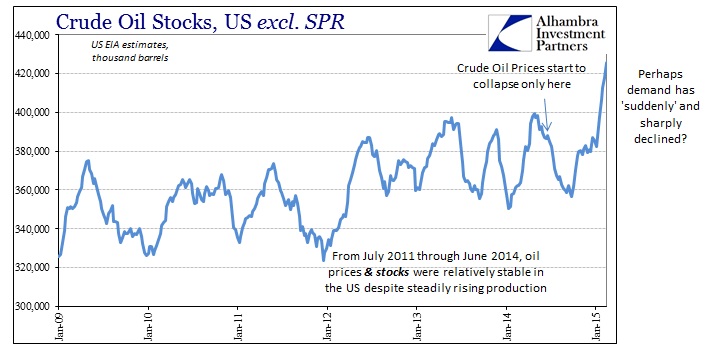

At the front end, rig counts have gained most attention but only as they relate to the surge in inventory. The US is overflowing with oil and production remains at a record high, but the two of those factors together don’t actually count as much in terms of price as is made out by most commentary. It is far too difficult for many to discount the entire economics professions’ complete dedication to the US “booming” economy in order to see a huge demand problem in oil prices; far easier to simply repeat the words “record supply” and leave it at that.

If you actually view the futures curve of late, the curves of recent days has crossed in the outer years. In other words, where prices have moved around at the shorter end, out at the long end the curve has shifted significantly downward regardless of short term pricing. That relates to both contango, as noted above, but also I believe growing recognition that supply is overwrought and demand is what may be impaired – perhaps more permanently than anyone thought possible only a few months ago.

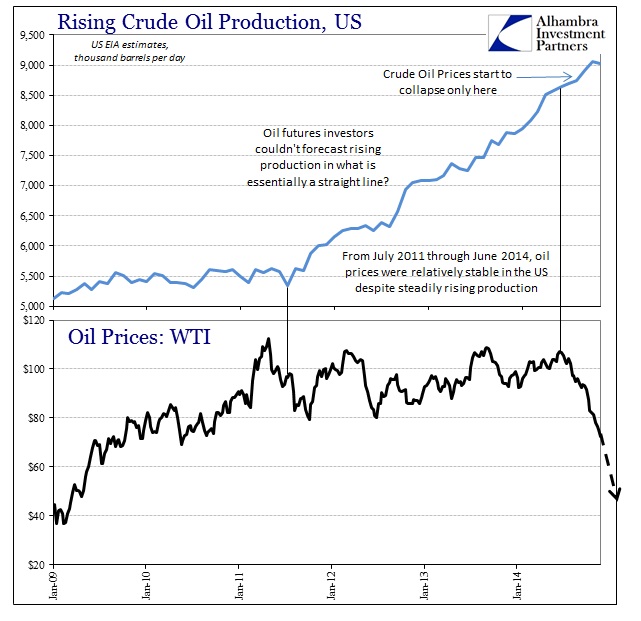

In order to believe that crude prices are solely a supply problem you simultaneously have to believe that futures investors are all stupid. This is not to say that they are never wrong, but in this case it would mean that they cannot even perform basic tasks of financial discounting in order to set an orderly and clearing market price. That is the only way you can look at “record supply”, which is clearly the case, and think it has anything much to do with the collapse in oil prices (latest monthly figures through November 2014).

US domestic supply has been rising precipitously since July 2011! And it has done so in a remarkably stable fashion, nearly a straight line to match even the S&P 500 in slope. In other words, “record supply” has been a continuous facet of oil markets for almost four years now and the trend in the level of production should not surprise anyone let alone futures investors. If anyone was surprised by the level of crude oil production heading into 2015, enough to sell, sell and sell to the tune of almost a 60% price drop, they had to be utterly incompetent especially as futures prices are supposed to be the purest form of discounting future considerations. The supply part of the equation is decidedly easy and clear.

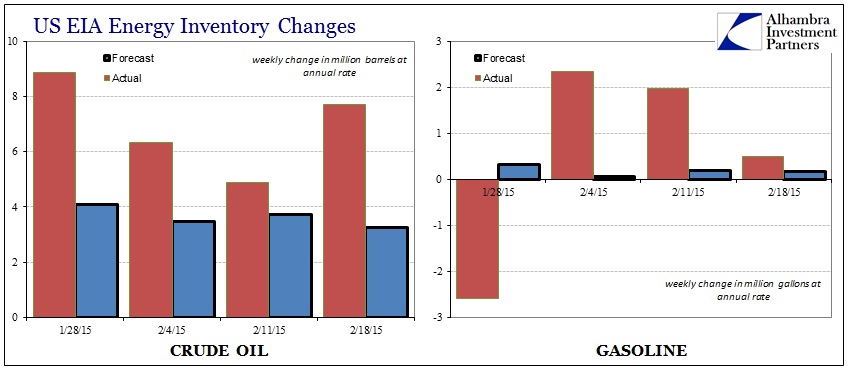

What is driving prices now is the record buildup in crude stocks, which has only recently become problematic.

Each weekly release of the US EIA estimates of crude inventory has been market-moving in January and February, to both fuel rebounds and kick off erosion in prices, because the amount of building inventory is immense.

Given the cumulative assessments here, it seems far more likely that if some variable has changed, and done so dramatically, it is not a “surprise” surge in crude supply but rather a sudden and sharp drop in demand that had reasonably matched growing supply until only more recently. The nature of futures markets being what they are, imperfect as they may be, it is even likely that investors there took financial cues in the “rising dollar” to mean that the probability of demand matching supply was falling. The heightened illiquidity into October and then December simply confirmed growing financial problems which would reflect in far lower probabilities of economic stability.

In other words, futures markets assume that supply may be a problem but only because now, all of sudden, demand, including US demand, will no longer keep up. The fact that such an imbalance created a nearly 60% collapse in price speaks to the growing probability of any economic shortfall occurring as well as the far more important and greater discounting of its severity and/or duration. It bears overstating that these kinds of price movements only occur during severe economic dislocations of a global scale.

Either all futures market participants are utterly incompetent or demand is the variable that shifted hard. Those are the only two possibilities.