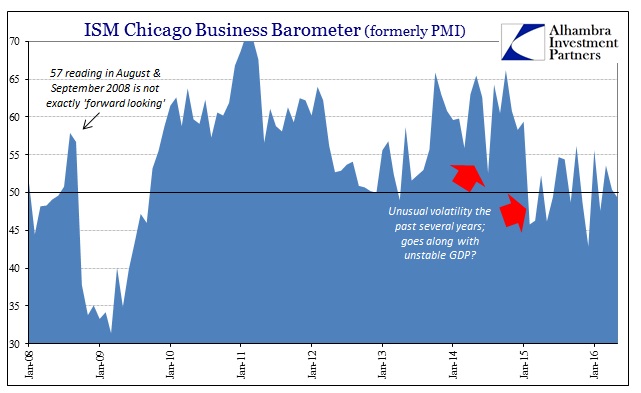

The ISM Chicago Business Barometer PMI fell back below 50 again in May, the ninth time in the past sixteen months that the index came out under the supposed dividing line. It is more likely, however, that US businesses especially in manufacturing just don’t know what to make of the past year and a half or so, and have switched more so to being cautious (even more than they already had been throughout this “recovery”). With the index average hovering right around 50, that might be the only way to interpret the violent mood swings in manufacturing sentiment in the Midwest.

According to MNI Chief Economist Philip Uglow:

Firms ran down stocks at the fastest pace for more than 6 years in May, and while a rebuilding over the coming months could support output, the underlying message appears to be that businesses are not confident about the outlook for growth.

It is rather amazing that the PMI could suffer such a huge setback and then remain under conditions of such stasis for so long. The Chicago BB started 2015 at 59.4, which the mainstream took as a forward indication that Yellen was right about “transitory” weakness. Unfortunately, the very next month, February 2015, the index dropped precipitously to 45.8. Since then, monthly volatility has been the operative condition in what can only be a war between believing Yellen and the business reality of this economy.

Each time it looks like weakness might only be short-lived, sentiment shoots higher only to be foiled in short order by continued “dollar” and economic pressures. The index jumped from 46.2 last May to 54.7 in July and 54.4 in August just as it appeared the initial slump at the start of last year might actually be as temporary as advertised – only to suffer through the events of August, with the index responding in September by falling back under 50. In October, it rose again as the FOMC declared “global turmoil” singular, only to drop to a new low of 42.9 by December.

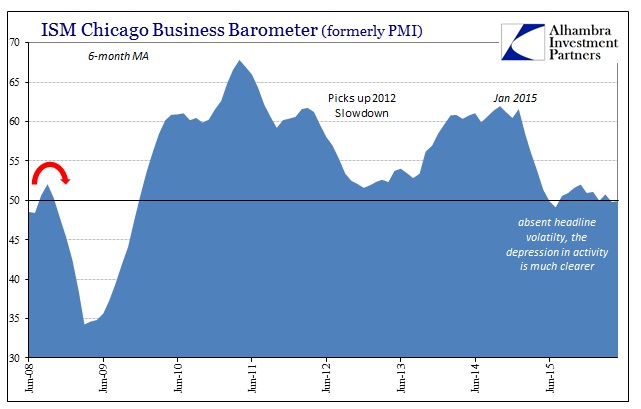

Since then, the index has been up and down with May being the first month this year to not change direction. In other words, as the index surged from 47.6 in February to 53.6 in March, that was not the expected rebound but rather more of this same unevenness marking these unusually sharp shifts in temperament. This volatility obscures what is absolutely clear in the 6-month average; the level of current production and indications of future production have been subdued for almost a year and a half.

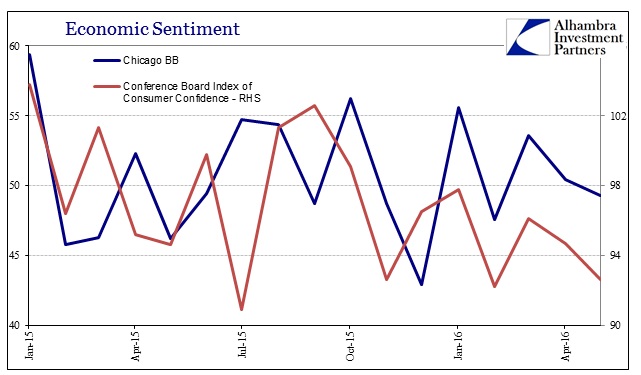

The general trend in manufacturing sentiment is an almost perfect mirror to consumers, as consumer “confidence” measures appear just as volatile but also stuck. The Conference Board’s measure of consumer confidence fell to 92.6 in May from 94.7 in April. All the movement was in those responding with negative sentiments about both current and future conditions. The proportion of consumers indicating that current business conditions were “bad” rose from 18.2% to 21.6% in May. At the same time, the share of respondents claiming jobs as “hard to get” rose from 22.8% to 24.4%. Those expecting fewer jobs in the near future also increased to 18.1% from 16.7%.

None of these measures are recessionary indications, however, instead pointing to an economy in a rut or curious limbo somewhere between recession and recovery (more so the former). It wouldn’t be much of a concern except that this condition has lingered for so long already without any resolution. If this were just some general weakness (something like the Asian flu slump in the late 1990’s), it should have dissipated. Instead, there is still just as much risk of recession now as when oil prices first crashed and economists were trying to suggest “strong dollar” as a positive international comparison.

Rather than further appeal to pseudo-precision, I believe these calculated measures of sentiment and confidence both point in the same general direction – to an economy that has been surprisingly weak for surprisingly far longer than it “should” have, and neither businesses nor consumers quite know what to make of it. If that is the correct interpretation, it wouldn’t be all that surprising since this current economic condition is unlike anything seen before, and thus new circumstances without precedent would be expected to generate lingering confusion and even these kinds of synchronized mood swings.