These crazy days of ours, if you want to have confirmation the economy is sliding into trouble, look at stocks: for stock-market jockeys, crummy economic data indicates that the Fed won’t raise interest rates. And stocks jump.

Maybe not jump, exactly. But the S&P 500 rose 0.9% for the week, its third weekly gain in a row, following another decline in industrial production, weak retail sales propped up by autos and restaurants, falling wholesales and business sales, rising inventories, a lackluster employment report…. The word “recession” is floating around, and when it hits, stocks might make a big new high. That’s the twisted hope.

And now Moody’s has jumped on the recession-warning bandwagon too, with a logic of its own.

First, there’s credit: the spigot is getting turned off.

For the last three weeks, only one junk-rated company was able to issue bonds in the US. And just in the US: “This is shaping up to be the worst October for the worldwide issuance of high-yield bonds” since October 2011, wrote John Lonski, Chief Economist at Moody’s Capital Markets Research. He warns of “reduced access to financial capital.”

But unlike October 2011, when the euro debt crisis caused wild gyrations in the bond markets, which then recovered quickly, this time around, there might not be an easy recovery: average yields and spreads are still low in comparison to 2011, but the average expected default frequency (EDF) for US/Canadian junk-bond issuers, which was 3.85% in October 2011, is now a “much riskier” 5.20%.

Then there are deteriorating corporate revenues and profits.

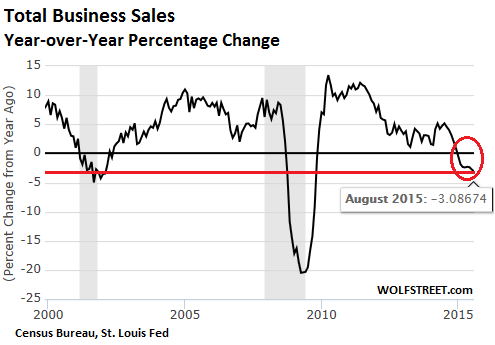

And Moody’s ties them to jobs. Hence the risk of a recession. Total business sales have been shrinking year-over-year, something they have done in recent years only during the prior two recessions:

But OK, this time it’s different. Revenues in the energy sector collapsed by 32% in Q2 from a year earlier. So the rest of the revenues should look sound, no? No. Moody’s removes energy from the equation:

The year-over-year increase of core business sales, or an estimate of business sales excluding sales of identifiable energy products, is likely to slow from Q2-2015’s already well-below-trend 2.1% to 1.7% for Q3-2015. The latter would be the worst showing by core business sales’ yearly percent change since the category shrank by -4.2% in Q4-2009.

They “Now compare unfavorably with pre-recession showings”

Moody’s continues:

Given the maturity of the current business cycle upturn, the latest deceleration by core business sales hints of rising recession risk. For the year-ended September 2015, core business sales probably rose by 3.2% annually. For all of 2015, that growth rate is expected to be slower than 2.5%.

By contrast, during the 12 month spans prior to the start of the previous two recessions, core business sales increased by 4.7% for the year-ended November 2007 and grew by 3.8% for the year-ended February 2001. Thus core business sales already, and are likely to continue to, underperform what held prior to the last two recessions.

Slowing business sales by themselves aren’t enough for an official recession. The NBER, which decides when a downturn becomes an official recession, uses all kinds of factors beyond just two quarters of negative GDP. Prominently among them: jobs.

And there’s a link between core business sales and jobs.

When sales are hot and rising, employers hire new people, and people work more hours and make more money and spend more money, which causes sales to tick up even more, which causes employers to hire even more…. The fundamental virtuous circle of economic growth, in theory. So Moody’s says that core business sales have “considerable influence over private-sector employment”:

For the current cycle, the moving yearlong average monthly increase of private sector payrolls peaked at the 262,000 jobs of the span-ended February 2015, which coincided with the most recent 5.0% peak for the yearlong annual percent growth of core business sales.

A subsequent deceleration by the annual increase of core business sales to the prospective 3.2% for the year-ended September 2015 helps to explain the deceleration by the average monthly increase of private-sector payrolls to the 217,000 jobs of the year-ended September 2015.

But 217,000 jobs per month – hose were the good old days. For September, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a gain of only 142,000 jobs and for August a revised 136,000 jobs.

If core business sales “do not accelerate materially,” Moody’s said, growth could drop below 100,000 new jobs per month. In this manner, core business sales “warn of jarring slowdown by private-sector payrolls.”

Which boils down to that “rising recession risk.”

As credit ratings agency, Moody’s is all about debt. What matters isn’t whether or not there is a recession, but what the Fed is going to do. And this is what Moody’s envisions: not only ZIRP as far as the eye can see, but if fewer than 100,000 new jobs are created three months in a row, “the expected direction of US monetary policy would probably shift from a rate hike to additional stimulus.”

And thus Moody’s confirms that the emergency monetary policies, designed to keep the decrepit, top-heavy, malodorous financial system from collapsing on top of its chieftains, have become a permanent fixture. Without these “emergency” policies, the economy is now deemed to be a permanent basket case, while the financial markets would simply give up their ghost.

But the monetary policies have allowed companies to load up their balance sheets with debt to the point that even Goldman Sachs finds it “increasingly alarming.” Read…. The Wrath of Financial Engineering: It’s Now Eating into Earnings