The University of Michigan released its September update for their surveys of consumers. The overall index of consumer “sentiment” was unchanged from August at 89.8, and up just 3% from last September. This “confidence” index peaked in January 2015 at 98.1 and has been sideways to lower ever since. Most of the internals were practically unchanged throughout, leading Chief Economist Richard Curtin to note:

…modest gains in the outlook for the national economy have been offset by small declines in income prospects as well as buying plans

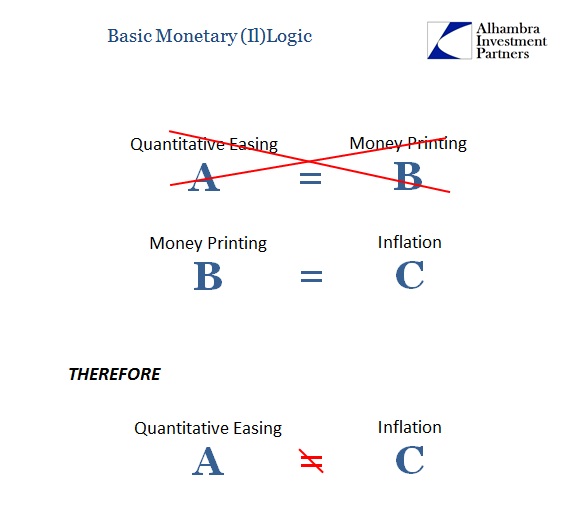

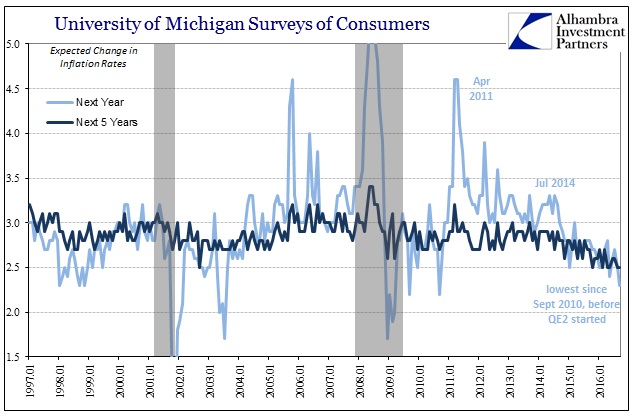

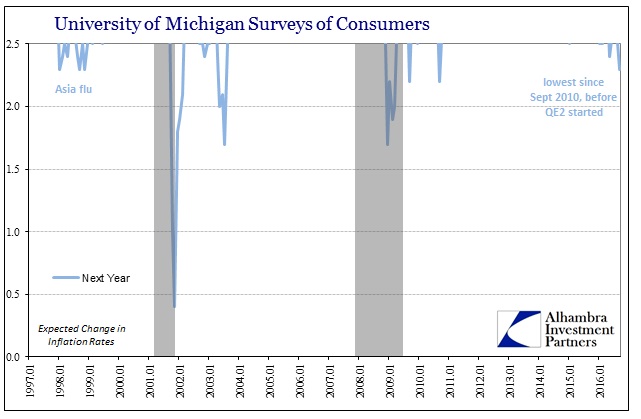

Not everything in the surveys was so uninteresting. Inflation expectations dropped yet again, as both short-term and intermediate consumer projections for the rate of prices changes continue to sink. The surveyed result for the inflation rate next year fell to 2.3%, the lowest since September 2010 just prior to the start of QE2. Straight away, it would appear that consumers are no longer so convinced that “money printing” actually accomplishes what money printing is supposed to.

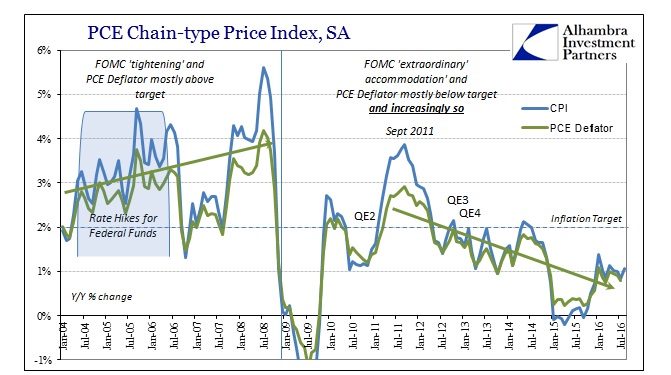

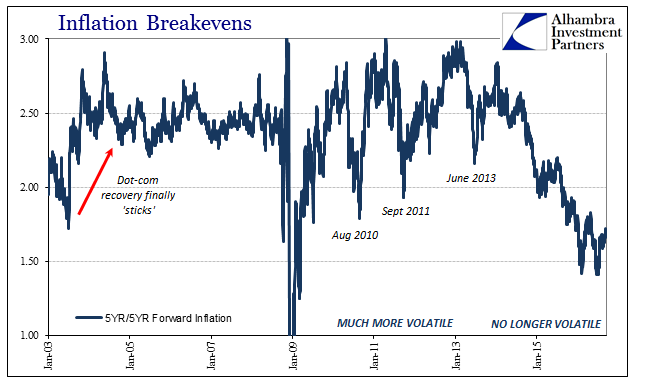

Since the data is made up of surveys of American consumers we are really talking about perceptions, and thus this reduction in expected inflation has been shaped by recent (money, not monetary policy) events. The peak outlook, the one most faithful to the myth of “money printing”, was reached not surprisingly in early 2011. Since then, shorter-term expectations were as inflation breakevens in the TIPS part of UST trading; seemingly stable but only as a matter of being unconvinced about policy efficacy, primarily QE.

The downward turn in expectations occurs first in the summer of 2014 with the appearance of the “rising dollar”, fully corroborating inflation breakevens concurrently moving against the recovery narrative. The next break lower happened last summer with the appearance of “global turmoil.” More importantly, however, despite the constant mainstream emphasis of temporary and “transitory” as well as the imposition of “full employment” at every possible juncture, expectations have only continued to get worse even this year in a clear sign of shaken faith in central bank power and efficacy.

In the past two decades, short-term expectations in the UofM surveys have rarely been as low as they are now and have been almost all year this year. While that means expectations for the short run are equivalent to 1998 and the Asian flu, there is tremendous difference given that there were not four QE’s “printing” trillions in bank reserves at that time intended to remove any doubt about Federal Reserve ability. To have expectations as low now as the Asian flu even after the Fed acted (supposedly) hugely and continuously is immensely significant.

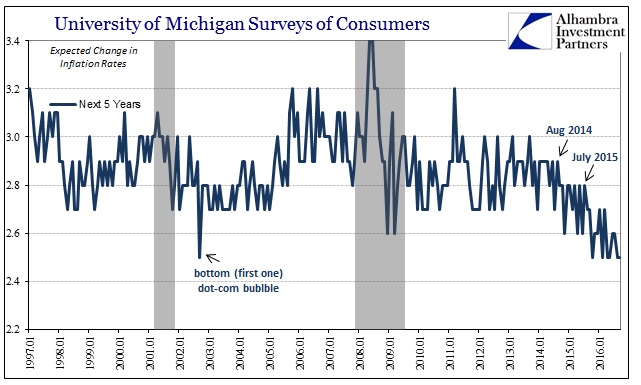

Longer-term inflation expectations reflect perceptions about what all this means. If faith in “money printing” is exceptionally low in the short run, that can only at best create greater uncertainty about what will occur beyond the short term in economic potential. It is thus reasonable to suggest that consumers are recognizing the full “cycle” in views about monetary policy; from first buying into it, then questioning it, and now disregarding it.

Again we find the same “dollar”-led inflections where regular Americans perceive these “dollar” events not as “transitory” random acts but as a pattern of further and further disproving everything that central bankers have been declaring all along. It is highly compelling that in the face of the appearance of “full employment” in late 2014, consumer expectations regarding inflation have followed the warnings in markets rather than the emphatic, heated rhetoric of economists; they declared success and nobody buys it.

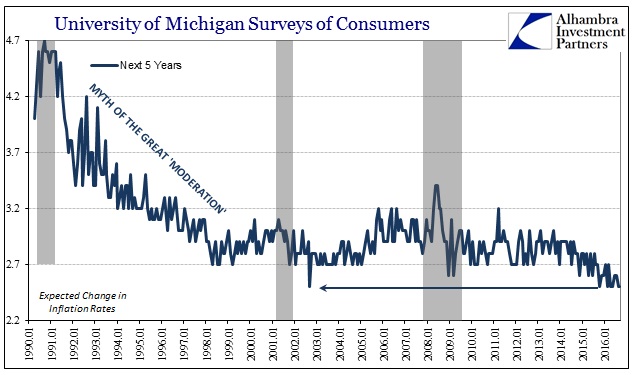

To emphasize that point, the only other time in the entire series (dating back to March 1990) where 5-year inflation expectations have been this low was September 2002 at the bottom of the dot-com bust. That was just one month at 2.5%, however, where in 2016 that low has been repeated five times since January, including the latest in September (and two other months were just 2.6%).

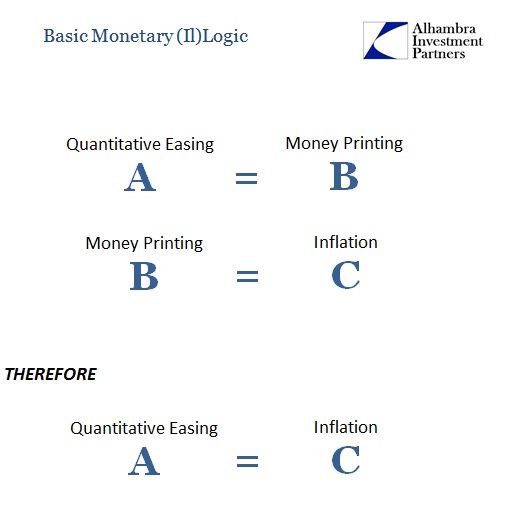

What we are witnessing here and in market trading of inflation expectations is the unwinding of the myth of the Great Moderation. This is not to say that calculated inflation rates didn’t moderate during the 1990’s; far from it. Rather, what is happening is the market and regular Americans are coming to realize (even if they don’t yet fully realize why) that the “low inflation” environment of that time was never due to monetary policy of the “maestro.” The economic stability of the 1990’s and 2000’s wasn’t so stable after all; it was largely a mirage where the cost of “purchasing” such artificial strength (by allowing through determined ignorance the eurodollar system to run wild all over the world) would have to be paid where John Maynard Keynes said it didn’t matter – the dangerously unsatisfactory long run that we now have to live in.

You would think this would be a big problem for economists and policymakers (redundant), but in their rush to hold fast to their ideology these kinds of contrary results are just set aside. In the case of inflation expectations that is the literal truth. Even published FOMC policy statements acknowledge that market-based inflation expectations have been ruling against them for some time, but the inclusion of consumer survey-based expectations in the contra column hasn’t elicited the required awakening. Instead, as usual, economists have rushed to dismiss now this data, too.

Writing for the St. Louis Fed at the end of last month, VP and Economist William Dupor declares consumers too stupid (my word) to be reliable:

The above evidence suggests that monetary policymakers may want to think hard about how they use individual inflation expectations surveys to inform monetary policy—at least until the nation’s economic education program raises the public’s understanding of inflation.

The public understands economy, money, and inflation just fine; after all, unlike Dupor they have to live in the wreckage that economists like him call recovery and success. I wrote at the beginning of this month in response that it isn’t just inflation expectations that are in the process of “de-anchoring”, a potentially fatal blow to orthodox monetary policy and its understanding (if it might be called that) of how this is all supposed to work, it is economists completely breaking from reality.

And thus we have found a new form of de-anchoring. Long run inflation expectations may be doing that all their own, but the more concerning and troubling de-anchoring relates to what we see here (again) of economists. Markets, as I said, long ago turned against them and now consumers are in the process of confirming markets – but to economists that just can’t be so both are judged to be wrong for whatever their alleged faults and set aside as meaningful data. The FOMC is only to be left with “professional forecasters” for determining whether or not inflation expectations are anchored properly, an incredibly crucial property of orthodox monetary policy. Since most if not all “professional forecasters” are themselves economists, really statisticians, once again we find economist policymakers relying upon economists forecasters to tell them what they want to hear no matter how much the rest of actual evidence ends up otherwise.

To an economist, the only thing that is “real” is what other economists and their models tell them is real. The economy that “should” be is all that matters because that is the one derived from mathematics. Nothing could possibly get in the way of what “should” happen, so anything that suggests as much must be the product of “irrationality”, “disequilibrium” (as in the case, twice, both 2007 and again in 2015-16, of eurodollar futures), or just plain uneducated stupidity. This is not science at all, it is Aristotelian farce; but dangerous farce because the whole world economy is stuck upon this one point. Monetary policy contains no money, and the rest of the world is finally realizing it even if economists refuse all the different and irrefutable ways of being shown.