We know that credit and funding markets took a nasty turn in December, but it wasn’t until economic data released just recently that we gained a better appreciation about why that might have been. In the relative blindness of “realtime” such market-driven bearishness could be self-contained within purely financial factors alone, and thus opens the possibility of ambiguity about why the banking system turned atrocious. Undoubtedly, that was the immediate concern of these markets anyhow, but nothing happens in a vacuum and if financial factors were a serious problem you would expect at least some passing relation to a more fundamental outlook.

That is what this “rising dollar” problem is at its most basic level, as the pullback in bank balance sheet extension, and thus liquidity in “dollars”, is a mathematical calculation of rising volatility; more specifically, expected volatility. Again, that “tightening” constraint could be purely financial as there are any number of massive imbalances that by themselves would demand this kind of reckoning, but in terms of timing the data is more and more suggesting the real economy as the primary and motivational catalyst.

What we have seen so far of January has been an absolute mess, among the worst results of this “cycle”, bringing some very important economic indications back in line with only the Great Recession itself (and worse than that in other geographical areas of the global economy). From factory orders and capital goods to exports and imports, the CPI and even Personal Consumption Expenditures, there is a growing sense that this winter has gotten far more “wintry” than even the past two.

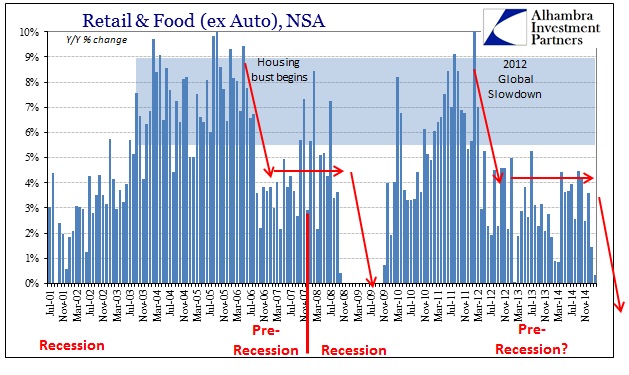

Retail sales were just as bad in January, but the latest release for February gives us the first glimpse as to whether this was an “aberration” yet again (oxymorons are a part of economic commentary under these conditions) or whether there really is a heightened risk of recession. To that view, February was even worse than January.

Even the seasonally-adjusted figures declined for the third consecutive month, including both autos and food sales which are about the only segments keeping retail sales from showing not just recession but bad recession. In other words, the monetary idea of “aggregate demand” or spending for the sake of spending is occurring but it only has left the overall economy in a state of duality where the worst part (the vast majority) has now slowed down everything else instead of the intended inverse. Such a precarious state raises recession probabilities by more than a little, which is what credit and funding have been really anticipating ever since June and July.

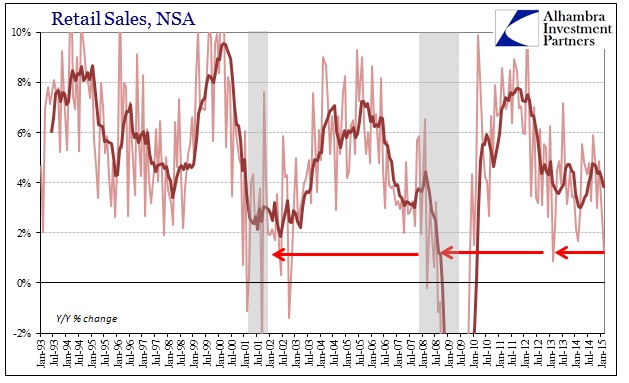

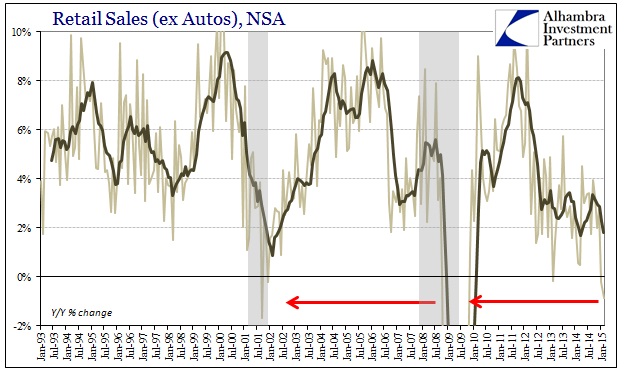

Even with food and auto sales included, February was the worst month since “winter” 2013 and on par with the recessionary conditions in the middle of 2008. If we extract food and autos, leaving about 70% of the total, the latest estimate was by far the worst since the Great Recession.

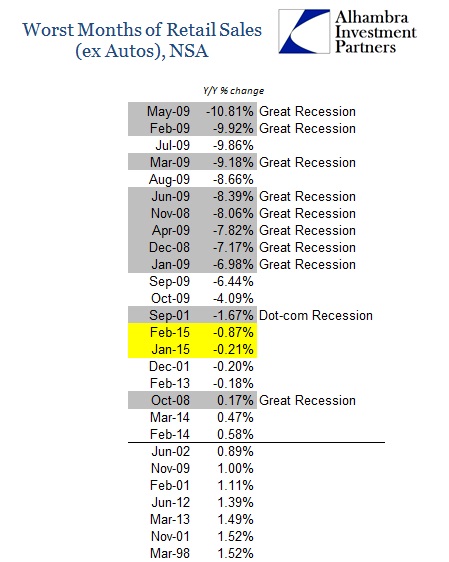

In fact, out of the 266 months of year-over-year growth in the data series dating back to 1992, February 2015 ranks as the 14th worst. The only months “ahead” are those at the absolute trough of the Great Recession, its immediate aftermath and September 2001 (which includes not just the dot-com recession but also September 11). Interestingly enough, and relevant to this point, Retail Sales including food may be better in absolute terms (+0.34% vs. -0.87%) but is still the 15th worst month in that data series.

The fact that January 2015 enters the same list only one step behind February 2015 is what is really important here. Actual consumer spending is developing a pattern that is consistent with only the worst parts of the series, as recessions are not just negative numbers but the accumulation of them (and, actually, in retail sales negative numbers are rare even for recessions which means that the accumulation of just low but positive growth is enough to be counted as full dislocation). And unlike either 2013 or even 2014, there isn’t a psychological “boost” of QE or anything that might “come to the rescue.” Instead, the FOMC is describing an economy that clearly doesn’t actually exist in order to do the opposite, monetarily speaking.

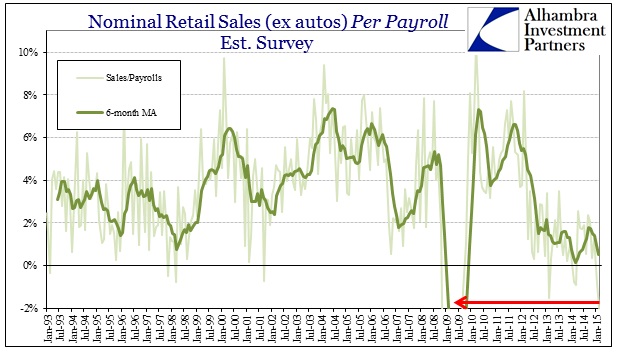

Perhaps that is the really important part of the outlook presented here, as the divergence between purported job growth and actual spending levels has rarely been as steep. That would either suggest that, again, these new jobs pay next to nothing and are thus economically useless or that they don’t exist in the first place. In either case, “demand” in the US economy is highly weak already and seemingly gaining deceleration.

This is all a pattern we have seen before, as the elongated business cycle is a prominent feature in the history of the Great Recession itself. From the slowdown after the housing bust until the collapse phase starting toward the end of 2008, there is a clear repetition of that in the years after the 2012 slowdown. If there is a difference it is only that the cycle has become even more elongated, which by itself may not be unexpected given all the monetary intrusiveness this time around – a damning indictment of it if it all ends up in the same place anyway.

Counting food sales, growth in retail sales in February 2015 (+0.34%) is actually slightly lower than October 2008 (+0.42%) when the entire financial complex was captured by full and sustained panic. With that perspective in mind, it is again the accumulation of these horrible comparisons that offer the worst case outlook. February has started off in that direction, so we will see if that is confirmed by other accounts of February and then, most importantly, if it all continues further into March. Should that occur, I would be fairly confident that recession had already begun – which means we might not know until April or May.

If, however, data for March or even April find a minor “bounce” that still may not change the overall situation enough, which is why the data so far, in my analysis, indicates only a higher probability of recession by rough comparison; even contraction rarely takes place in a straight line. The accumulation of bad data, the broad scope of those accumulations across data series, and then market confirmation of a broadly and sustained pessimistic outlook certainly argue convincingly for at least that.