By James T. Areddy at the Wall Street Journal

[David Stockman’s Note: Next Wednesday, I’m streaming an urgent, live video broadcast from my living room in Aspen, CO. I believe the most popular investment of the 21st century is about to implode. The collapse of this $3 trillion bubble could be the “final nail: in your retirement if you’re unprepared. But, if you invest in a discreet alternative investment right now your savings could be spared… and you could actually make up to 300% by July. That’s why I’m hosting this live video training from my home. I’ll lay out all of these details and more for you. All you need to do is RSVP right here before your spot is taken. There’s nothing to buy in order to get access — it’s free.]

SUIZHOU, China—Even in China’s remotest places, relentless overproduction—here it is mushrooms and cement trucks—is clouding the country’s path to prosperity and jolting the global economy.

When 48-year-old farmer Yang Qun began trading at Suizhou’s bustling morning mushroom market a half decade ago, the fungus industry was expanding, even attracting a rural lending arm of British financial giant HSBC Holdings PLC. Ms. Yang saved enough to buy a minivan. When wet snow fell last month, she was settling for closeout prices to unload six bags of dried mushrooms that took a half year to cultivate.

For Xu Song, a clanging sound was once a welcome reminder that his 200 colleagues were busy pounding steel into the giant barrels used on cement trucks. On a recent day, he sat alone watching videos in an unheated office, the only worker left on an abandoned factory floor where dozens of rusting barrels were stacked like multi-ton footballs.

“The decline was steep,” says Mr. Xu, standing inside the all-but-defunct Hubei Aoma Special Automobile Co. factory, where he was hired to do quality control. “I don’t know what had really happened to us.”

Beyond the glut of steel and apartments that weighed down growth in recent years, China’s economy is also saturated with surplus goods from farms and factories. Numerous small and midsize cities such as Suizhou, which boomed on easy credit and government support for agribusiness and construction, were supposed to provide the second wave in China’s growth story. Instead they are now sputtering, wearing down prices, profits and job opportunities.

The struggles in Suizhou show how China’s slowdown is broad and deep and hard to fix. It has fueled volatile market trading around the world and has contributed to anxiety about potentially stalled U.S. growth. Domestic overproduction means China is now spending less overseas, while businesses that sell to China are bracing for possible protectionist moves aimed at propping up local companies. And with Chinese demand at risk, its industrial giants with idle capacity are looking to capture market share abroad, including construction and railway equipment makers.

The government has made a priority of eliminating “zombie companies,” kept alive with loans to produce unneeded goods, to clear the path for more vibrant parts of the economy. The squeeze won’t be easy because in small, remote places such as Suizhou, overbuilt industries are often the economic backbone.

Chinese manufacturing remained slack in January, including the weakest reading for the government’s official purchasing managers index since August 2012. Chinese steel production fell last year for the first time in over three decades. Bank and utility credit grades are getting cut, as rating firms do math that suggests looming debt problems.

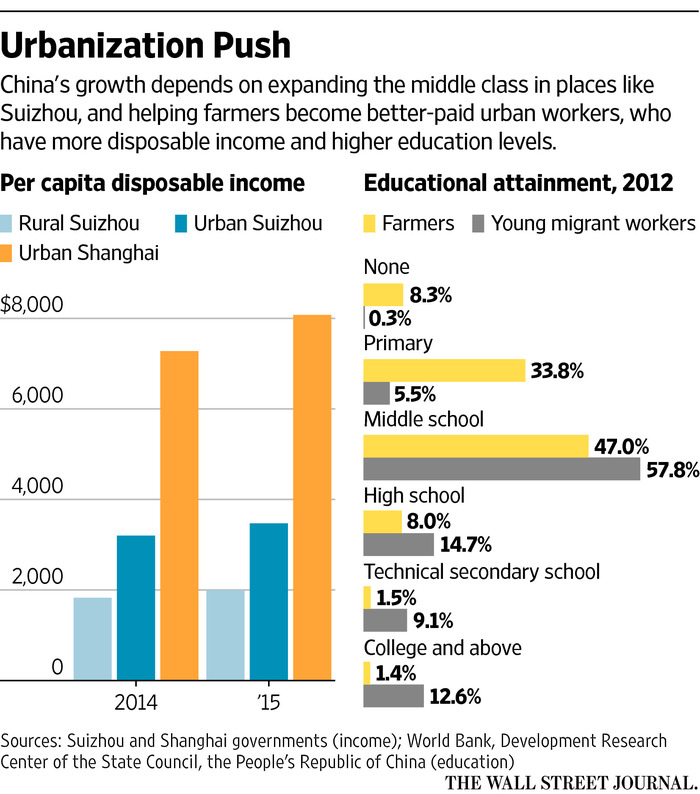

China’s future is dependent on spreading opportunity more widely. While Shanghai and other gleaming metropolises on the coast powered the first decades of market liberalization, Beijing is now counting on smaller cities for the next phase. The government aims to urbanize 100 million lower-income people within five years to expand a middle class that can afford movies and medicine, and sustain China’s upward trajectory.

With a population of 2.5 million, Suizhou is one of about 130 smaller cities in China at the threshold of this effort, acting as magnets for turning farmers into better-paid urban workers and building new markets for local businesses. Disposable incomes of city dwellers in Suizhou ran about $3,470 per person in 2015, according to the government. That is more than 40% above what its rural residents earned but less than half the nearly $8,100 enjoyed in Shanghai.

“Cities stuck in the middle, they just don’t know what to do,” says Michele Geraci, head of an economic policy program at Nottingham University’s campus in the eastern Chinese city Ningbo. After speaking with officials in various governments around the country, he says, many are in “industrialization limbo” between rural and urban.

Today’s slowdown is partly indigestion from an earlier stimulus. New tech companies and a wave of industrial upgrading are concentrated on the coast, while a recentbreakdown in China’s financial markets is only narrowing the options for companies wanting to expand.

To clear the way for new growth, Chinese leaders have identified the supply side of the economy as the focus for policy this year. They want to weed out the overhang of excess capacity blighting many corners of the economy.

The funk is apparent in seaboard eastern cities such as Rugao and Nantong, which are suffering from excess shipbuilding capacity and swelling ranks of jobless. Too many producers of plate glass in the northern city of Shahe have led to factory closings in what locals like to call China’s Toledo. On the island province of Hainan, where small time fisheries have helped make China the world’s biggest producer of tilapia, many are now struggling to survive.

The metals, coal, cement, aluminum and glass industries alone could lay off three million workers by shuttering a third of the capacity, estimates China International Capital Corp., though the Beijing-based investment bank says government programs would cushion the blow for many and it sees signs authorities would pare industry slowly to protect growth rates.

North of the Yangtze River in Hubei province, Suizhou is the county seat for the surrounding hill country of fertile terraced fields. Pronounced “sway-joe,” it is the purported home to the mythological father of Chinese agriculture from 4,500 years ago known as the Yan Emperor Shennong.

To industrialize, it took advantage of proximity to the provincial capital, Wuhan. Low-skill workshops modified truck chassis from regional giant Dongfeng Motor Corp. to make cement mixers, garbage haulers, school buses and the like.

When the world economy cratered in 2008, localities such as Suizhou got added attention as Beijing greenlighted stimulus.

Suizhou financed a new urban district, anchoring it with office buildings and widened a village road into a boulevard it named “Welcome Guests.” The city issued $150 million in bonds and fancied up its riverfront by adding an arena with twinkling white lights. It built apartment towers near a station on the national high-speed rail network.

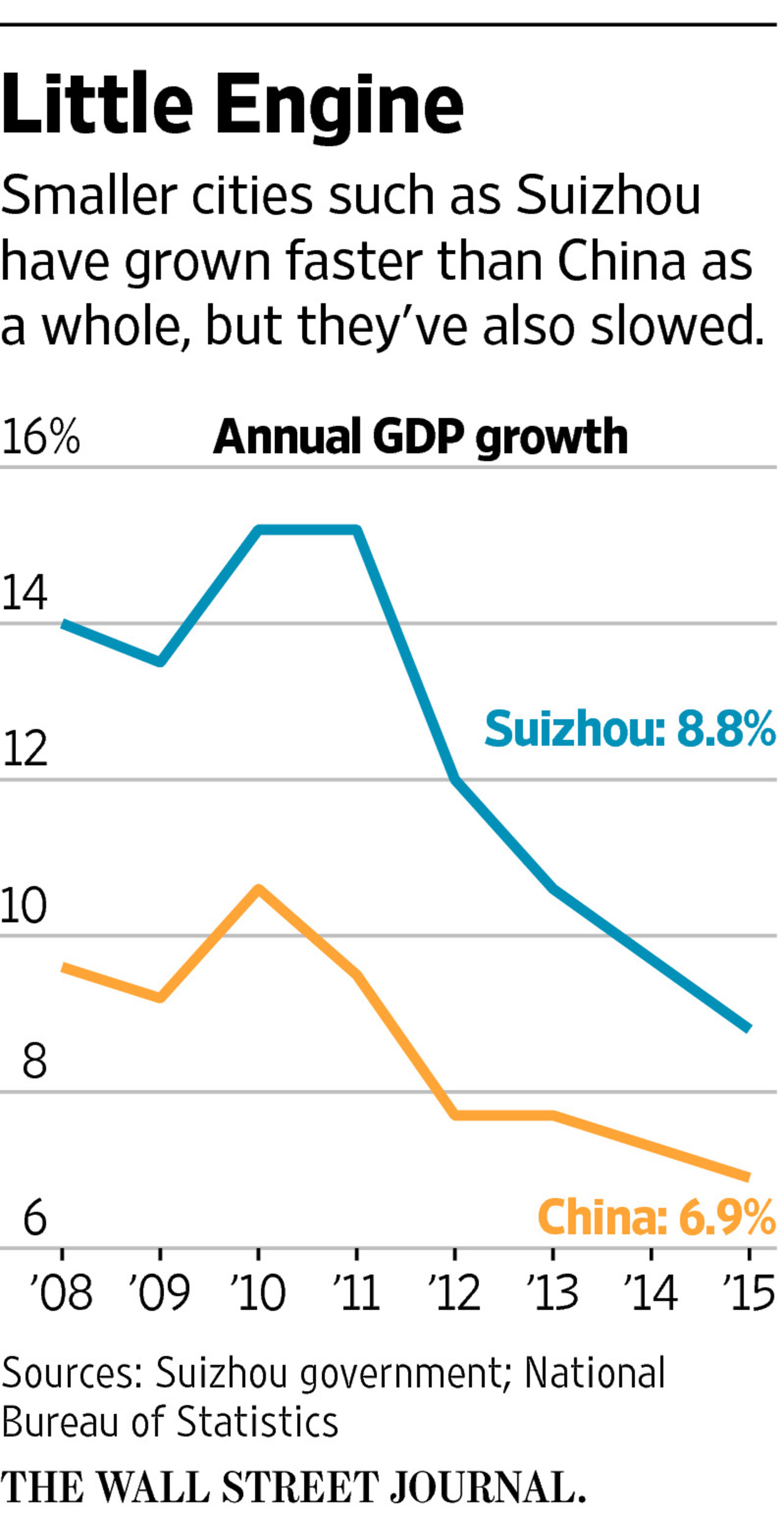

Suizhou’s gross domestic product during the past eight years expanded an average four percentage points faster than the nation as a whole, including back-to-back years topping 15% in 2010 and 2011. That pace eased to 8.8% in 2015, when all of China expanded 6.9%.

As the tide ebbs, excesses are being exposed. The city now has 110 large-scale specialized vehicle makers.

Zhou Fang entered the business after college five years ago to sell $60,000 water-tanker trucks for local producer Hubei Dali Special Automobile Manufacturing Co. While demand remains stable from government customers around the country, Ms. Zhou says she has 200 local competitors and too little repeat business. “It’s not like fashion,” says the 27-year-old, where customers come back every year to buy new clothes.

At the cement truck maker Aoma, Mr. Xu said it used to be so busy that “from outside the factory, you could hear the roar.”

The problems became apparent suddenly in mid-2015 when orders for the $60,000 mixers stopped arriving from its biggest customer, Xuzhou Construction Machinery Group Co. Among the handful of vehicles on Aoma’s vast lot outside was a mixer decorated with the yellow logo of Xuzhou. The company didn’t respond to questions.

Questions about the local economy put to the Suizhou government by The Wall Street Journal are being considered, a spokesman said.

Sitting on a red chair wearing pink slippers and an antidust outfit, 28-year-old Xia Yue is perched on the cutting edge of Suizhou’s hope to generate new opportunities. A quality control inspector at Hubei TKD Crystal Electronic Science and Technology Co., Ms. Xia operates a machine that tests crystal oscillators smaller than rice grains that act as tiny timepieces in mobile phones, Wi-Fi devices and cars.

TKD was founded in Shenzhen near Hong Kong, but its owner moved the company to his hometown a decade ago to take advantage of incentives offered by the government, which hopes advanced manufacturing will contribute longer-term growth in the economy and better jobs.

But TKD’s expansion hinges on a planned $36 million initial public offering in Shanghai, which has been awaiting approval since mid-2014 from securities regulators. Following recent stock market turmoil, the China Securities Regulatory Commission said it would approve offerings at a “rational” pace so as to not further damage the market.

And the business itself is cutthroat, depending on high production with tiny margins. TKD charges electronics companies just pennies apiece for the oscillators, and its customers are paying more slowly, according to public filings.

At the mushroom market outside town, Ms. Yang says she doesn’t know much about economic issues but senses activity is slowing.

She and her husband started growing shiitake about five years ago. Countless neighbors did the same. Hothouses growing mushrooms on shelves of cut logs cover the hills around Suizhou.

Shiitake is the Japanese name for the edible fungus that is called xiang-gu in Mandarin, and China now provides 80% of the global supply. Suizhou’s commercial bureau says the city is the country’s biggest exporter of shiitake, accounting for $610 million in business activity. HSBC located its first Chinese bank outlet outside a major city in Suizhou, in part to support local mushroom farmers.

Among the shiitake buyers circling the daily market at daybreak was Sanyou (Suizhou) Food Co.’s Qian Kejun. He said he can always find customers for good mushrooms in China, Malaysia or the U.S. But “excess supply” has pushed prices lower, said Mr. Qian, sniffing at Ms. Yang’s offerings as not worth her asking price.

After watching farmers with superior mushrooms get over $10 per kilogram, Ms. Yang was asking $6.40. Fretting that humidity would cause damage if she didn’t sell before this month’s Lunar New Year holiday, she settled for around $5.65 per kilogram, nearly $2,000, to unload her giant bags in separate deals with a woman in polka dots and a man in fatigues.

“I lost money today,” said Ms. Yang.

Source: Overproduction Swamps Smaller Chinese Cities, Revealing Depth of Crisis – The Wall Street Journal