By Wolf Richter a Wolf Street

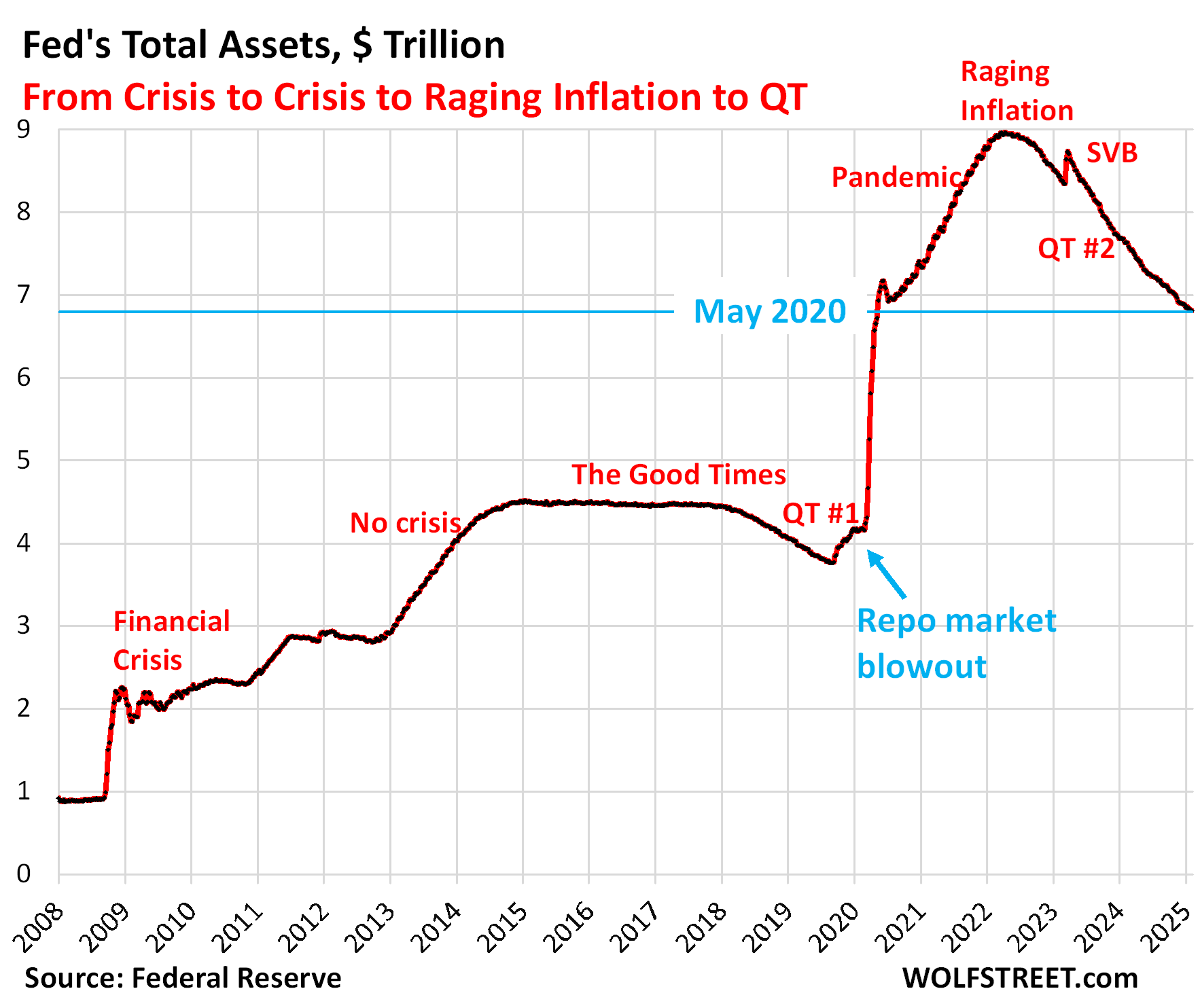

Total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet declined by $42 billion in January, to $6.81 trillion, the lowest since May 2020, according to the Fed’s weekly balance sheet today.

During May 2020, the third month of its mega-QE, the Fed had added $510 billion in that month alone to its balance sheet. So at the current pace of QT, we’re going to be saying “the lowest since May 2020” for about another 4-5 months. By the time we can say, “the lowest since April 2020,” the balance sheet will have dropped below $6.66 trillion.

Since the end of QE in April 2022, the Fed has shed $2.15 trillion, or 24% of its assets. Of the $4.81 trillion heaped on the balance sheet during pandemic QE from March 2020 through April 2022, the Fed has now shed 45%.

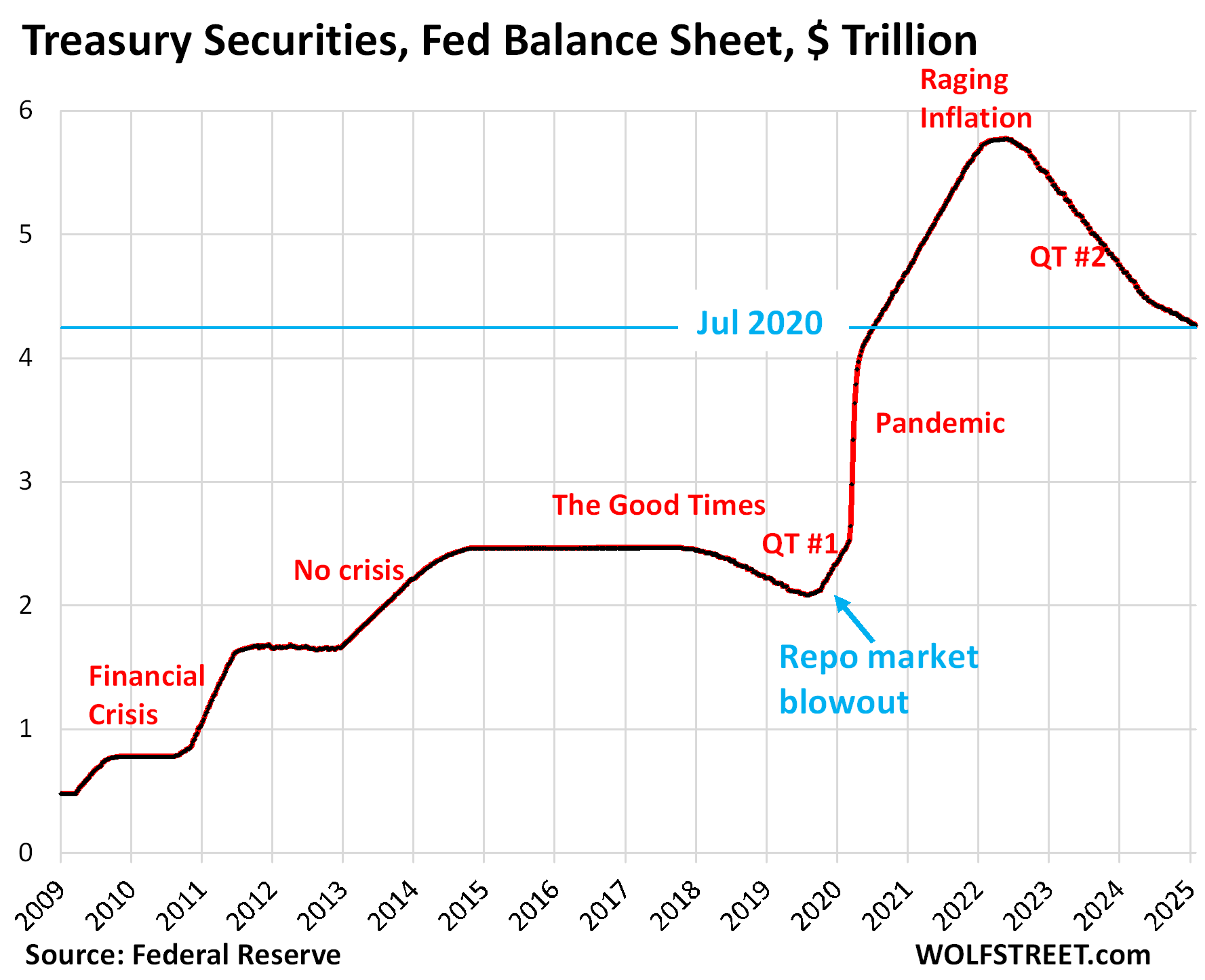

Treasury securities: -$25.2 billion in January, -$1.51 trillion from peak in June 2022, or -26% since the peak, to $4.27 trillion, the lowest since July 2020.

The Fed has now shed 46% of the $3.27 trillion in Treasuries heaped on the balance sheet during pandemic QE.

Treasury notes (2- to 10-year) and Treasury bonds (20- & 30-year) “roll off” the balance sheet mid-month and at the end of the month when they mature and the Fed gets paid face value. Since June, the roll-off has been capped at $25 billion per month. About that much has been rolling off, minus the amount of inflation protection the Fed earns on its Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) that is added to the principal of the TIPS.

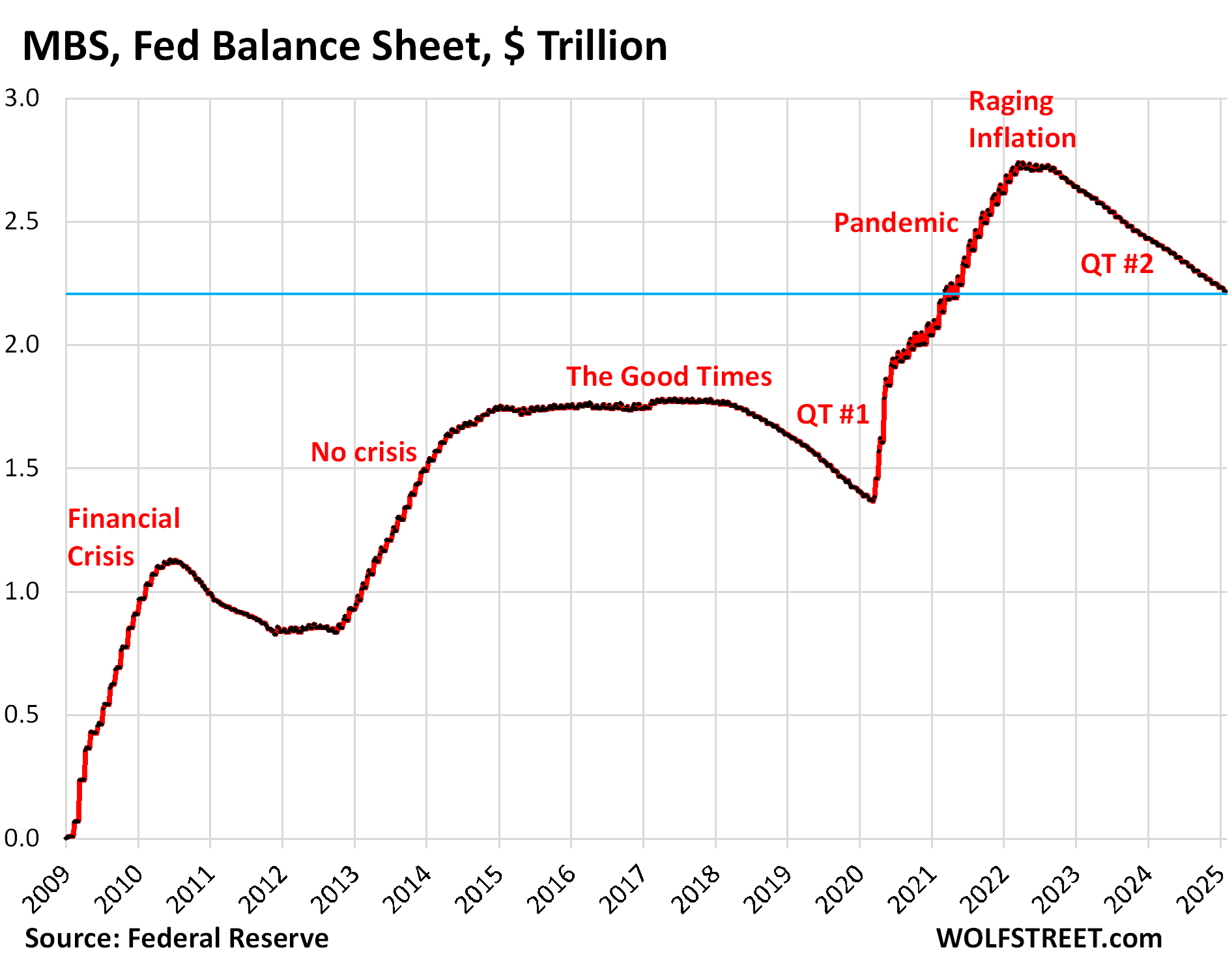

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): -$15.7 billion in January, -$522 billion from the peak, to $2.23 trillion, the lowest since May 2021.

The Fed has shed 19.1% of its MBS since the peak in April 2022. In terms of the MBS that the Fed had added during Pandemic-QE, it has shed 38%.

MBS come off the balance sheet primarily via pass-through principal payments that holders receive when mortgages are paid off (mortgaged homes are sold, mortgages are refinanced) and when mortgage payments are made. But sales of existing homes in 2024 have plunged to the lowest since 1995 and mortgage refinancing has collapsed, and therefore far fewer mortgages got paid off, and passthrough principal payments to MBS holders, such as the Fed, have become a trickle. As a result, MBS have come off the Fed’s balance sheet at a pace that has been mostly in the range of $15-17 billion a month.

The Fed only holds “agency” MBS that are guaranteed by the government and is therefore not exposed to losses if borrowers default on mortgages; the taxpayer would pick up those losses, not the Fed.

Bank liquidity facilities.

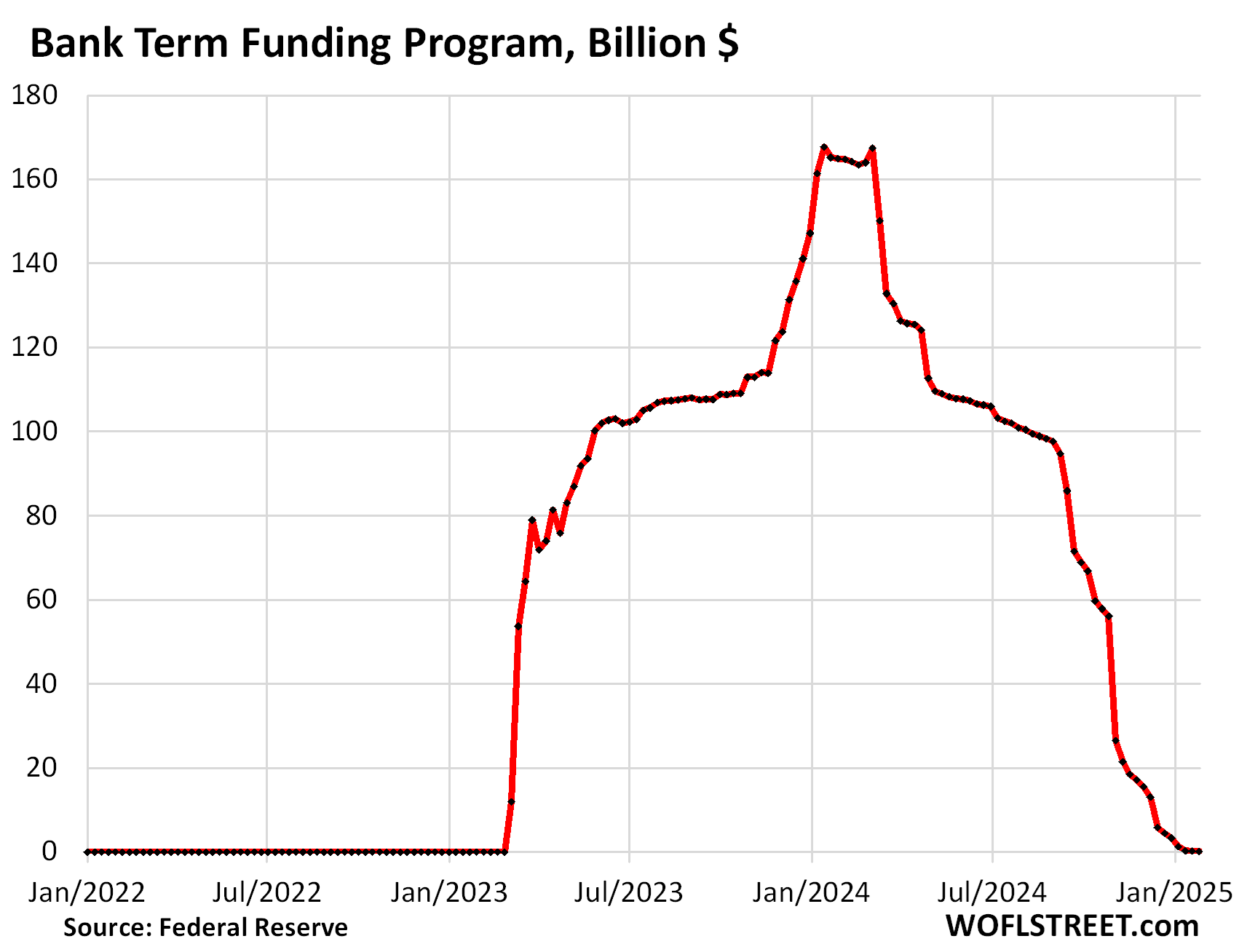

The Fed has five bank liquidity facilities. Four have either no balance at all or a balance that is essentially zero on the Fed scale, though they were heavily used after the SVB collapse. The latest addition to that essentially-zero list is the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP):

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps ($76 million)

- Repos ($0)

- Loans to the FDIC ($0).

- BTFP ($197 million).

Bye-Bye BTFP: -$4.2 billion in January, to $197 million, down from $168 billion.

The BTFP was conceived in March 2023 after SVB had failed. But it had a fatal flaw: Its rate was based on a market rate. When Rate-Cut Mania kicked off in November 2023, market rates plunged even as the Fed’s policy rates were unchanged, including the 5.4% the Fed paid banks on reserves. Some banks then used the BTFP for arbitrage profits, borrowing at the BTFP at a lower market rate and leaving the cash in their reserve account at the Fed to earn 5.4%. This arbitrage caused the BTFP balances to spike to $168 billion.

The Fed, infuriated, shut down the arbitrage in January 2024 by changing the rate and decided to let the BTFP expire on March 11, 2024, and no new loans could be taken out since then. Nearly all remaining loans, which had a maximum term of one year, have now been paid off.

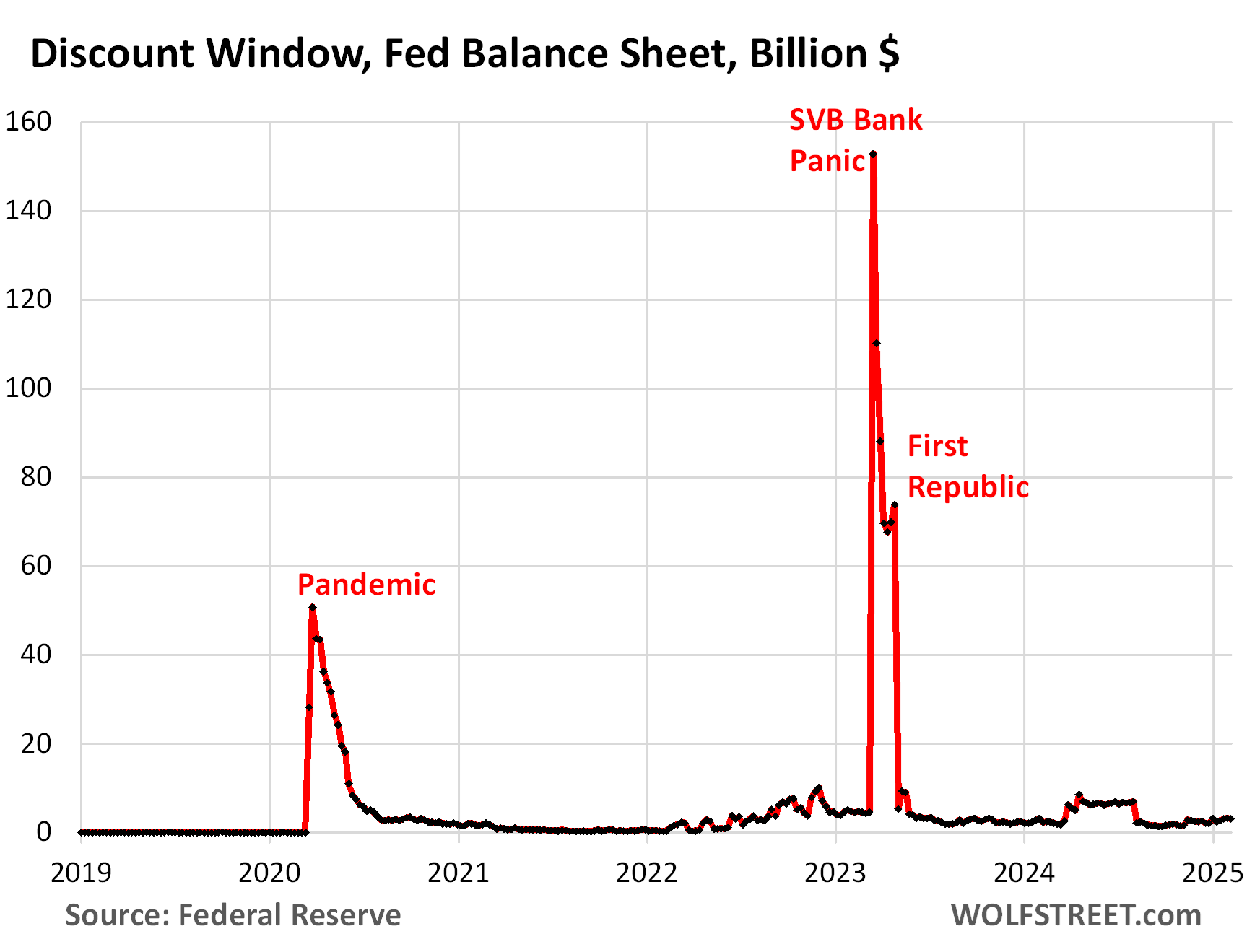

Discount Window: -$132 million in January, to $3.1 billion. During the bank panic in March 2023, loans had spiked to $153 billion. Even this balance qualifies as “near zero” as the chart below shows.

The Discount Window is the Fed’s classic liquidity supply to banks. As of the rate cut in December, the Fed charges banks 4.5% in interest on these loans and demands collateral at market value, which is expensive money for banks.

Powell has been publicly exhorting banks to use this facility more often, and practice using it with small-value exercise transactions, and to even get set up to use it, which many banks apparently are not, and to pre-position collateral so that they can use it when they need to. But there is stigma attached to borrowing from the Discount Window, and banks are reluctant to do it.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how: