The capital and now loss projections for Deutsche Bank are, as much as they can be, more straight forward. In terms of Credit Suisse, the dubiousness of the implications is proportional to the “story.” Whereas Deutsche last week shocked Wall Street (and Europe) with a huge potential loss in FICC activities (their CB&S segment), any actual surprise was far overdone because of two confluent and related trends – the global economy’s “unexpected” reduction this year and where Deutsche placed its resources to try to take advantage of almost all its peers undergoing sustained eurodollar withdrawal.

As noted last week, Deutsche raised “capital” in May 2014 in order to advance its activities in fixed income and fixed income trading (money dealing) surrounding leveraged loans, junk bonds and emerging market debt. Therefore, a reduction in global “dollar” liquidity alongside a related swoon in such risky fixed income isn’t going to add up to very good numbers for Deutsche – especially after the fireworks in August and September.

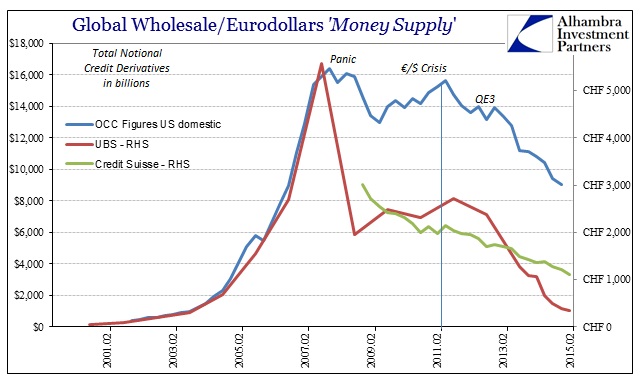

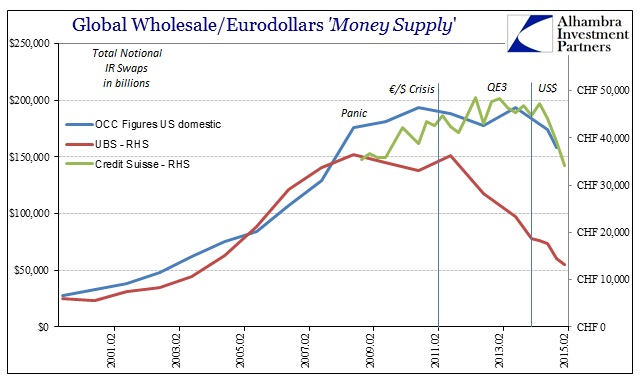

Deutsche, however, was not alone in its contra trend speculation. There were others looking to profit from the general disdain toward eurodollar activities post-2013 (and, of course, euroeuro activities; “euro” being simply the shorthand designation for offshore money dealing), most notably Credit Suisse. In sharp contrast to its bitter Swiss rival UBS (and that was the intent), Credit Suisse like Deutsche Bank promoted greater internal exposure to eurodollar activities in seeing that market different than the morass affected by all the rest. We don’t, however, know exactly if Credit Suisse embarked upon the same business lines and portfolio/resource allocations as Deutsche, but it wouldn’t be unreasonable to think that they did in at least broad outline and purpose if not fully equivalent.

That suspicion grew mightily when last week Credit Suisse suddenly, and for no truly given reason, announced a huge increase in “capital” restructuring. Given the trends in regulatory firming, the “market” was expecting some share issuance to shore up leverage ratios but CHF5 billion was far, far more than anyone imagined. Such a number must come with, as the Wall Street Journal notes, a damned good “story.”

When a company wants money, it needs to tell a good story about what it will do with it. In Credit Suisse Group’s case, the bank will need a better reason than just covering losses from restructuring if it is to raise upward of five billion Swiss francs ($5.18 billion).

Tidjane Thiam, the Swiss bank’s chief, will almost certainly have a tale to tell about investment opportunities, too. Otherwise, it is hard to see investors ponying up the cash.

As usual, however, the Journal author leaves this on an almost-inspiring note. Leverage is only a focus on the downside whereas bulking up under the right conditions leaves great room for opportunity:

But leverage is only half the story. Credit Suisse may have to make provisions for further fines and its restructuring. For investors to fund those, they will have to feel certain these are the final costs before returns improve significantly. That would be a good story.

From this view, you infer that Credit Suisse is projecting that “good story” by simple fact of it appealing to the market right now even where its stock is conspicuously trading at a significant discount to its implied one-year forward book value. Maybe that really is the case, and the bank is, like 2013, forecasting nothing but green from here on. But what if Credit Suisse’s “story” is instead Raghuram Rajan’s?

The world economy, he said, was “looking grim”, with weakness in industrialised countries putting paid to the export-led growth models of emerging markets. “Growth is clearly weaker than we would like in India, partly because global growth is weaker . . . We’re pretty much an open economy.”

Mr. Rajan is Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and former chief economist at the IMF. While the mainstream media particularly here in the US still focuses on Janet Yellen’s “transitory” excuse, the realistic nature of foreign markets and especially money markets is looking at the world far, far differently. Given what we can infer further about Credit Suisse and what it had done during the initial stage of that global turn (mid-2013 taper problems and then full “dollar” after June 2014) it is difficult to see how the bank, already admitting it made a mistake during that period by axing the CEO who moved them to so participate in it, is projecting sustained money dealing bliss with its capital affirmation. Since we are dealing with balance sheet math, the sunshine just doesn’t add up.

It is, in my view, far more likely that Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank are proving that renewed bank resources supporting what was left of the eurodollar system were badly misused. If that is the actual “story” and that the global economy’s increasing downside potential reinforces that nature, then the problem for global “dollar” liquidity and money dealing going forward is more than the belated catching up from Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse. In other words, in yanking further support from the “dollar” (dark leverage and all) by growing necessity already this year, these banks set up a further downward spiral across the whole global “dollar” participation for the balance of this calendar and at least the next turn of it.

The Journal’s “story” for Credit Suisse is much, much more inviting and warm, like any good fairy tale, but it doesn’t hold to much correlation or corroboration aside from economists who fail to prove their words time and again. Declaring “sudden” losses and upsizing “capital” by an order of magnitude is far less soul affirming, but much more aligned with the grand order of economic and financial reality especially in the second half of 2015 (though right at home in the first half, too). To that end, we have to again view the whole within the main idea of “transitory.” Economists want desperately to see that as the baseline, but it is increasingly hard to ignore how these moves especially in banking and eurodollar function are evidence of growing rejection of it.

That possible view is further measured by the context in which Mr. Rajan’s comments were made. Speaking at the IMF-World Bank gathering, he was pressing for greater “liquidity” commitments on the part of developed nations even though there might not be as much appetite for it now (because, contra the Journal, even developed nations are currently pre-occupied by the potential for animating and immediate downside):

Mr Rajan also called for a “global safety net” backed by the IMF to provide support to economies that might experience liquidity crises in the future, especially given that such problems might be triggered by the reversal of years of highly accommodative, post-crisis monetary policy in advanced economies such as the US.

Without such a safety net, governments were reluctant to approach the IMF because of the stigma attached to such a plea and the implication that they were undergoing a full-blown solvency crisis rather than a temporary shortage of liquidity as billions of dollars of capital rushed for the exit.

In short, the world wouldn’t really need a “global safety net” if banks were flush (and getting more so) with “capital” and truly confident in seeking out the opportunity that “must” come with it. If the “dollar” is truly transitory in its turn of the past eighteen months, then there is little to actually fear in that regard. Banks would see far past any regulatory leverage demands, no matter how stark, and would be lining up to expand all over it – that is what wholesale banks live for, as seen in all prior bubble incarnations on the way up. That they so clearly are not (in fact, doing the opposite), leaving instead EM central bankers to contemplate and argue for permanent and expanded central bank dollar swaps, more than suggests how to continue interpreting all this.