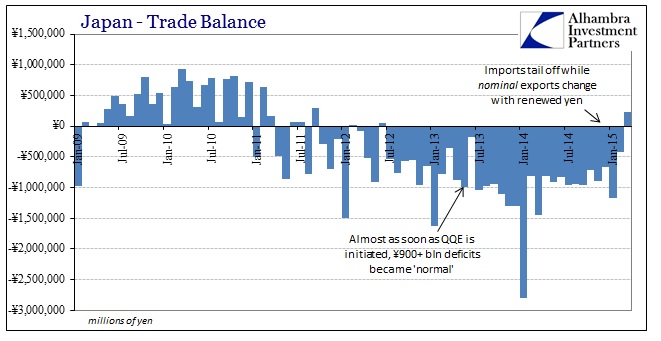

For the first time since June 2012 Japan has attained a trade surplus. It is, however, premature to interpret that as an end to the impoverishment the island has undertaken these past three years, the last two under QQE. There are various reasons for the end of the negative trade imbalance, but the most significant surround the Chinese New Year.

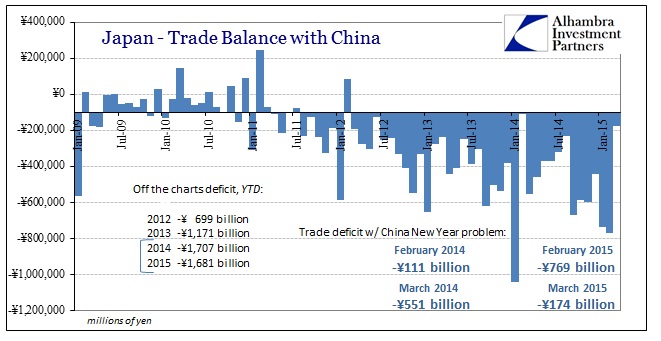

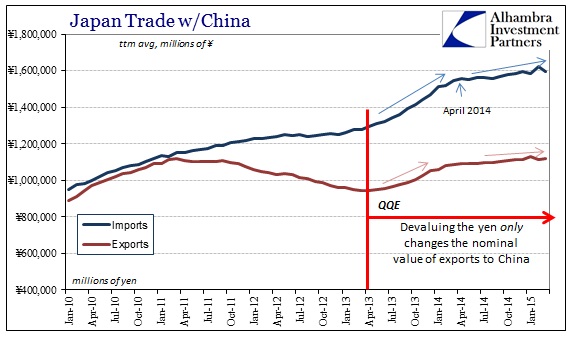

China’s annual holiday plays havoc with any number of economic accounts of its own, but it should not be surprising to see its closest trade partners under the same difficulties in measurement. Unfortunately for Japan, as QQE was intended to foster trade in the other direction, China remains the most visible and deepest supplier for Japanese industry. As such, the level of activity from China is the largest single source in variability – with crude oil imports now a distant second, contrary to expectations.

The overall March surplus for Japan was just under ¥230 billion, but imports from China fell 19.4% in March. That was undoubtedly an adjustment for activity in February, as imports from China surged almost 40% that month. This exchange in monthly trade balance with China more than accounts for the Japanese surplus: February’s deficit with China was ¥769 billion on that surge in imports, while March’s deficit came in at only ¥174 billion. Thus without the China’s variability there would still be a serious trade deficit in March for Japan overall.

Taking the quarter as a whole, 2015 trade with China is almost as negatively imbalanced (from Japan’s perspective) as 2014. Recall that January 2014 was the worst single, monthly trade balance in Japanese history, and more than a third of that was due to China importation alone. Despite that huge discrepancy last year, Japan’s trade balance with China this year so far is almost exactly as bad. In other words, the problems that the yen debasement initiated are still plaguing the Japanese.

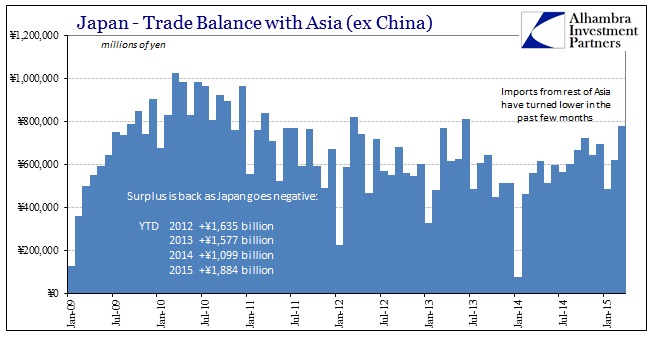

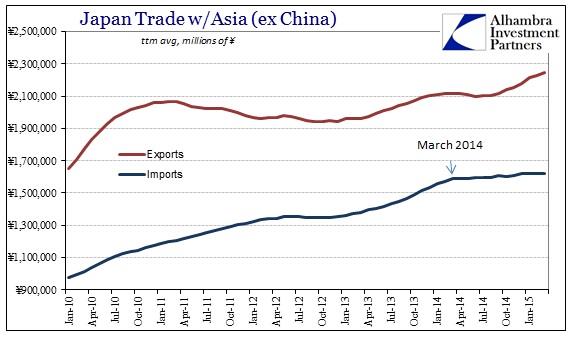

The only real benefit, that isn’t calendar variability, is that the Japanese economy has clearly slowed down if not re-contracted. Oil prices are once more being used as an excuse, but you can clearly see a change in import behavior starting in either March or April (the big fall) of last year. That is particularly true of imports from the rest of Asia apart from China.

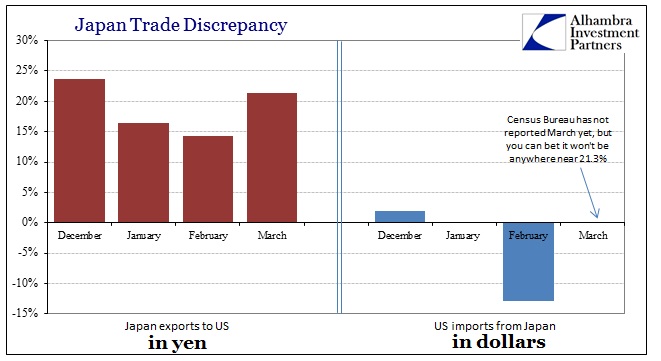

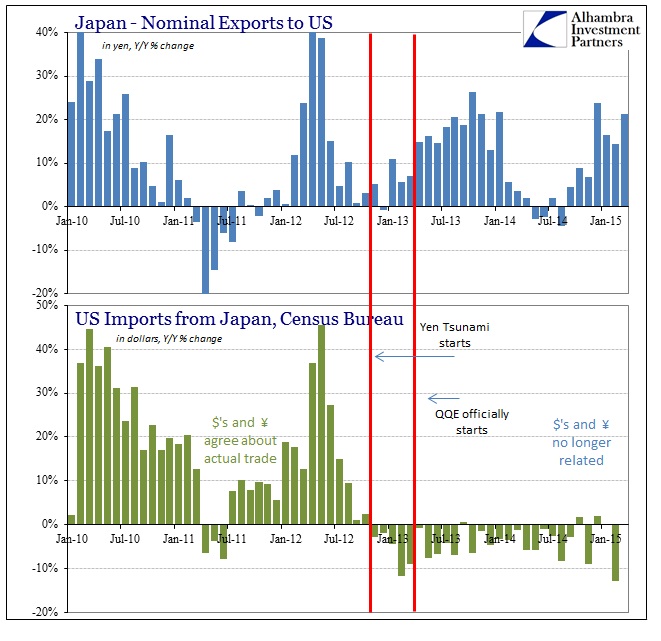

On the export side, we can be reasonably assured that growth in that sector is the same monetary illusion that has been enacted since late 2012 when Abenomics first evolved beyond mere whispers. The Japanese show overall exports gaining 8.5% in March but that is a nominal figure that doesn’t count the impact of the yen’s recent slide (which is visible above). So, for example, when the Japanese Ministry of Finance shows a 21.3% gain in exports to the US, the Census Bureau on the other side will estimate something far, far different.

We don’t have a March figure yet from Census, but the discrepancy in February was enormous; Japan reported a 14.3% gain in yen terms while the Census Bureau showed a nasty 12.9% decline. Those two numbers should largely match but they have not since the monetary illusion was unleashed.

That leaves Japan “achieving” finally a trade surplus due to Chinese variability surrounding its arrogation of Japanese productive capacity, the monetary illusion that makes the yen value of exports rise even where it is more than likely that actual trade volume decreased, and the fact that the internal Japanese economy is again falling apart and now needs both less energy and less material. I think that is a perfect metaphor for monetary policy and how it intends to achieve much of anything.

This is all very much like the ECB’s naked attempt at manipulating money rates toward Eonia and Euribor – it looks closer to what it “should” but only because of all this monetary fakery. In monetary theory, that counts for all the heavy lifting which is why lack of actual progress should not be so astounding to anyone with common sense. So where the ECB has constructed a Potemkin money market, the Bank of Japan can now point to its own Potemkin trade balance to obscure as Japan circles the drain.