By Ken Brown at Wall Street Journal

For lovers of dramatic numbers, China has long been a gift. The flood of cash leaving the country has produced another impressive statistic: We are witnessing the greatest episode of capital flight in history.

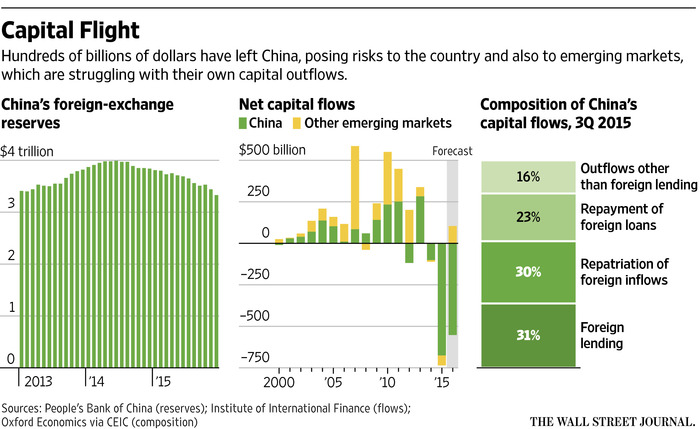

China’s foreign-exchange reserves fell by $700 billion last year. The flood of cash across its borders is complicating the country’s economic transformation and is raising the risks of problems in other emerging markets, where cash already is flowing outward.

“What happened in 2015 coming out of China was unprecedented in magnitude,” saidCharles Collyns, chief economist for the Institute of International Finance, a global trade group for the financial industry.

The size of China’s $10 trillion economy and its still-huge foreign reserves means the outflow won’t cause an immediate crisis in the country, though there are risks. According to World Bank data, the $700 billion decline in China’s foreign-currency reserves is bigger than the total foreign-currency reserves of all but three other central banks in the world—Japan, Switzerland and Saudi Arabia. China’s outflows are the biggest in absolute terms, although other countries have had larger outflows relative to the size of their economies.

The big worry is that China devalues its currency, which would come at a time that money already is flowing out of emerging markets as investors grow more risk averse and the U.S. Federal Reserve slowly begins to raise interest rates. If the yuan does fall further, it makes the economies of its Asian neighbors less competitive. That could lead to more capital flight from emerging markets, which could drain foreign-currency reserves in countries trying to keep their currencies from falling. Places that do see their currencies tumble also could face inflation, slowing investment and tapering growth.

Most historical cases of capital flight have one main cause—economic turmoil, political instability or an outside crisis that leads investors to pull their cash home. In China, however, there are several interconnected reasons that both locals and foreigners are pulling out their money, and the combination appears to be making the situation worse.

First, billions of dollars were invested in China on the assumption that strong economic growth would continue and the yuan would keep appreciating. Both assumptions have been proved wrong.

Second, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s corruption crackdown and the effort to blame finance-industry executives for last summer’s stock-market collapse have led many people to try to get their cash out of China, whether or not it was earned illicitly.

The dream of many Chinese to have their children educated overseas is another cause of long-term capital outflows.

One big source of the outflows will likely ease this year. Many Chinese companies borrowed in dollars in recent years to take advantage of lower interest rates outside China. A weaker yuan has made that borrowing more expensive, so companies have been rapidly paying off their dollar debt, often by borrowing at home.

Finally, the flows are driven by a belief that it will only get harder to move money offshore. Individuals are limited to $50,000 a year, though there are multiple ways to get around the restrictions. The Chinese government isramping up efforts to stem the flood of money with new rules making it harder for foreign companies in China to repatriate earnings and for investors to move yuan overseas.

The biggest problem for China so far is perception. Capital flight signals a loss of confidence in the government’s ability to run the economy. The perception is made worse in China by the government’s opacity and by the economy’s difficult transition from reliance on big infrastructure and exports to consumer spending.

“Capital fight is driven by nervousness and lack of confidence,” said Dev Kar, chief economist at Global Financial Integrity and a former International Monetary Fund official who tracks money flows. “If I am confident of the country’s future, I don’t need to send money out.”

The other risk to China is a cash crunch. While this appears unlikely, tight money could make it harder for heavily indebted companies and local governments to roll over their loans. “If you’re going to tell the story of a serious downturn, that’s one of the biggest sources of risk,” said Andrew Tilton, the chief Asia Pacific economist at Goldman Sachs.

Compared with China, the impact of capital flight has been much worse in Russia, the other major recent example of large outflows. The $330 billion that flowed out of Russia in 2014 and 2015 was far bigger relative to the size of the economy and had a far greater impact, contributing to a collapse in the ruble, a sharp contraction in the economy and a tightening of liquidity.

That China has been able to avoid all that shows the country’s economic strength—including a solid capital-account surplus—and the tools available to Beijing.

“China doesn’t need to shut the outflow, just contain it,” Mr. Tilton said.

Source: Hundreds of Billions of Dollars Have Fled China. Now What?