Just a few weeks ago the Swedish central bank, Riksbank, was being lauded for its courage and action in finally embracing QE as the ECB had done. The deflation problem in Sweden had been, so it is asserted, seemingly intractable and thus forcing the monetary hand once more. Riksbank has never been shy about fine-tuning here and there, so it was somewhat unusual the reticence to embrace full-blown action. While orthodox economic understanding dominates in Swedish policymaking, there was, at first, at least some acknowledgement about financial irregularity in that reserve – worries, specifically, about a housing imbalance.

“Inflation” will take precedence particularly without any countermanding factors to dispel what Paul Krugman has dubbed the “deflationary vortex.” Dr. Krugman had even made it a point to single out Sweden last year and it seems that his criticism stung – so much that Riksbank joined ZIRP last October.

That would place Sweden alongside Japan as a candidate to do the most harm to its own economic system. After all, the Japanese in embarking upon QQE were absolutely and unambiguously sure that “inflation” would cure all economic ills on the island. Instead, the lack of “global growth” has doomed exports at the same time inflationary cost pressures have destroyed consumer standing, all the while hollowing Japan Inc via productive capacity searching for stability elsewhere. Should Sweden follow Krugman’s advice for every developed economy (bigger, bigger and more bigger monetarism), and thus follow the path toward systemic poverty and further impoverishment? It makes little sense in common logic, let alone in everything cited above where Swedish monetary policy is less its own than Krugman et. al. can ever imagine (or model via DSGE).

To that end, Riksbank seemingly relented last night, dropping its benchmark repo rate all the way to zero – Sweden joins global ZIRP. How much longer before Riksbank is criticized into QE, as the ECB?

As it turns out, almost exactly in tandem with the ECB, Riksbank went full QE in February. That seemingly combined track between Sweden, a country that remains outside the Eurozone, maintaining its own currency, and the noosed nationalities of Europe is itself important. So, like Europe, when Sweden finally generated a small manner of inflation in May it was taken, as the ECB, for dispositive evidence that QE was both the right decision and was clearly working.

Swedish consumer prices unexpectedly rose in May, easing pressure on central bank policy makers to cut interest rates deeper below zero.

Consumer prices rose an annual 0.1 percent in May, the Stockholm-based statistics office said on Thursday. Economists estimated a 0.1 percent decline in a Bloomberg survey while the Riksbank foresaw unchanged prices. Underlying consumer prices, adjusted for mortgages, rose an annual 1 percent, beating the 0.8 percent increase estimated by economists and the 0.87 percent rise seen by the Riksbank.

My interest in Sweden is as much generic monetary systems and economic interaction as with Sweden itself. In that respect, watching the Swedes follow in the mainstream pattern is absolutely useful in demonstrating, as with everywhere else, the futility of these attempts. Again, the main theoretical progression is liquidity to lending to economy, with the last of those being “fortified” or demonstrated by inflation, defined only as some version of a CPI or deflator meeting some official target level. In Sweden, as in the US, that target is 2%; but the Swedish, as the American, central bank has failed to even get close to that for going on four years. The Swedish CPI, shown below, makes it difficult to understand any excitement about May’s “inflation”, which is revealing in how monetarism, particularly QE, is left to highlight and oversell the smallest of steps in the forecast direction.

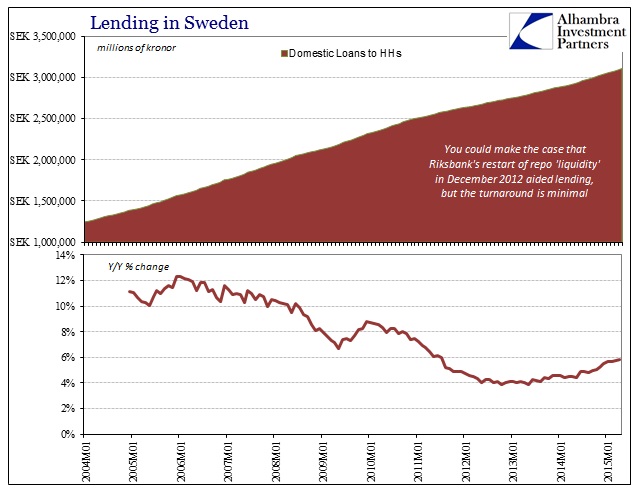

In that larger context, there is no variability which can easily be traced to whatever Riskbank was doing or was not doing. The CPI had been positive intermittently here and there going back to the start of all this “deflation” fear. The bank started repo “liquidity” again in December 2012, just as the Fed engaged QE4, to what avail? The longer the Swedish calculations for inflation linger below the target, the more desperation is unleashed which suffers the economy in the form of susceptibility to Krugman-ism. Since monetarism, as Keynesianism, holds itself as not falsifiable, there is only one direction that these actions can take (more/worse) regardless of what has not been achieved through the whole of it so far.

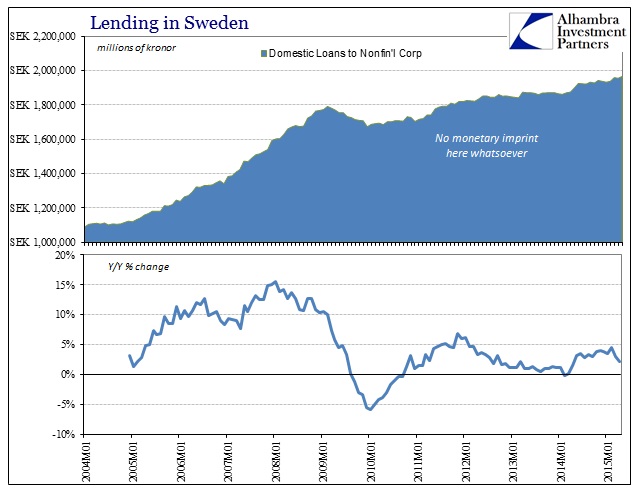

That often leads to contradictory appearances and ultimately confusion on the part of those assuredly proclaiming their undoubtable abilities. In this case, the monetary activity into “liquidity” and then lending takes the form of lower interest rates. Some of that gets more ephemeral than theory would like, as any QE is usually left to “portfolio effects” alone with the central bank acting purely upon government bonds. In other words, the theory is if the central bank can bring down the benchmark “risk-free” by taking in a good proportion of overall supply, the “market” will be left searching elsewhere for actual investment (hopefully in the form of actual lending) with a much lower benchmark by which to start.

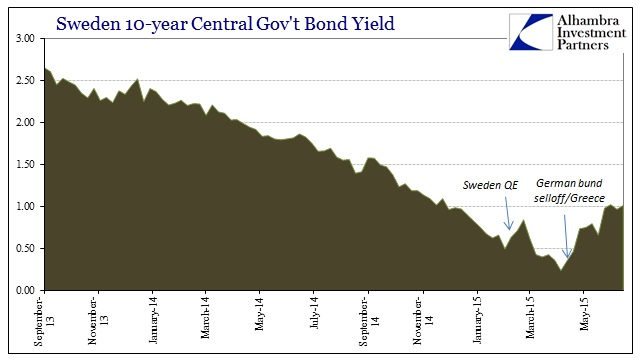

The problem with Swedish QE, as Europe, as the US, is that benchmark yields have been falling steadily since September 2013 without much “aid” via artificiality on the part of monetarism. That was, of course, almost exactly identical to the track of the German bund 10-year which unifies the interest rate course in Sweden with that of broader Europe (at least the “core”).

What good, then, was Sweden’s QE to do where nervousness, uncertainty, and even outright fear over the euro hadn’t already? In fact, again unsurprisingly, Sweden QE has failed to do much of anything as the benchmark bond continues almost hand-in-hand with bunds. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t actual impressions from QE, as those mostly reside on the “wrong” side of the ledger.

Quantitative easing is supposed to drive down longer-dated yields. But as investorsobsess over market depth, the Riksbank’s bond purchases are undermining liquidity and driving Swedish yields higher.

“The financial conditions — the currency and the bond yields — are moving in the wrong direction,” Roger Josefsson, chief economist at Danske Bank A/S in Stockholm, said by phone. The assumption is that “the Riksbank wants yields to go down and the krona to weaken, but it’s been the opposite direction recently. That should pose a problem.”

In short, QE doesn’t really work the way everyone seems to think it does – a universal factor that is present in every jurisdiction where it is tried. Quantitative Easing, for all the complexity the semantics of it conjures, is actually just that sort of misdirection. It is left as an experiment for rational expectations alone, as wholesale finance does not so easily move in the manner in which central banks seem to, somehow, still believe occurs. This is no longer surprising, as in the case of QE in the American version ran into negative liquidity trouble as far back as April 2011 in exactly the same manner – subtracting enormous amounts of collateral from repos.

The Federal Reserve refused to admit it; at first. Now it is universally acknowledged as such, as the FOMC itself demonstrated, if quietly, all the way back in 2013. In terms of broader interpretation, QE is left to work only as those financial agents actually believe in it; it is the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus. Actual liquidity in wholesale systems is offended by what QE does in terms of operational transactions, meaning that there is a whole host of evidence throughout the world (with which I am trying to add Sweden) that shows QE performs the opposite as intended on liquidity in the first place.

As to the leftover “portfolio effects”, those, too, unify Europe and Sweden as there are almost none in the manner in which there are supposed to be at least some. If QE is even effective in terms of just psychology, then lending is the end result which then builds into the real economy and shows up, according to theory, in the CPI and elsewhere. As shown above, the CPI has no notice of anything Riksbank has done so far, and you can add lending to questionable efficacy.

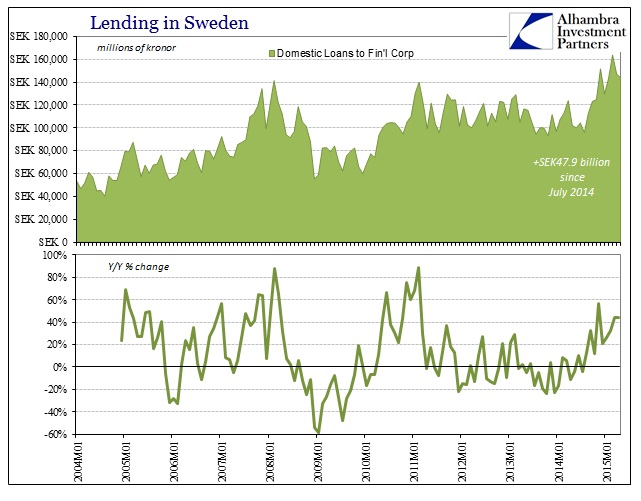

There is, however, one fashion in which QE does seem to have grand effects, though in the context of just Sweden and concerns over any building bubble these may not be so desirable. As in Europe, the lending increase is exclusive to financial firms since last July, meaning that, here too, Sweden is tied to Europe and the financial irregularities that survive any and all attempts to manipulate them into coherent results as demanded by monetary theory.

None of this should be surprising, as the FOMC in the US was ridiculing the Bank of Japan over its QE failures as far back as 2003. Yet, despite all consistent observations everywhere around the globe, they still do it without any significant alterations, only re-factor size and quantity. In that respect, QE has always been disingenuous as its terminology implies, strongly, that there is brandishing precision with which it is wielded by monetary “scientists.” That simply isn’t the case, as it never works as intended and continues more than a few quite harmful counter effects that lead, on net, in the wrong direction.

While Swedish experience here is very important in establishing that point yet again, it must not be left to that alone. As monetarism’s charm fades with these kinds of scattered outcomes, never reaching even close to initial promises and expectations, that will, I fear, inevitably lead back to the raw Keynesian distinctions of what I called the second age of socialist economic experimentation – from the end of WWII until the rise of the eurodollar standard in the 1970’s, monetary command of the economy was left far behind “fiscal” means to do the same. As QE fails universally, that direction appears far more attractive, especially politically, in the context of malaise and even renewed global recession.

But just as fiscal socialism failed by that time, leading to a radical alteration in the global paradigm, this monetary-driven third age is promising the same kind of prospects. It would be entirely a shame if that were to include, yet again, solely as a pendulum shifting back and forth between only monetarist socialism and fiscal socialism (as Krugman’s influence is certainly leading in that direction, starting with the persistent criticism of “austerity”). The global economy is proving quite impervious to commandments, a factor owing in large part to the massive inefficiency with which central planning exists and operates. In short, the answer to the global economic problem is clearly not greater inefficiency, yet that is all that is supplied and on offer.