Last week, the St. Louis Fed published an article based on a speech that Dr. Larry Summers gave to the Homer Jones Memorial Lecture series back in April. The article included the full text of Summers’ speech and importantly the supporting material and evidence he used in his argument for “secular stagnation.” Included is one chart that is among the most extraordinary and significant that I have seen in some time.

First, it is important to note that I agree with Dr. Summers about the idea of secular stagnation but for vastly different reasons. Thus, the term applies to the effect, not the cause. In his lecture, he points out that the first usage of the phrase was in the late 1930’s by economic Alvin Hansen. It was Hansen more than perhaps any other who was responsible for delivering Keynes to America during the Great Depression, working very closely with him throughout the ordeal. This is why, of course, Hansen has been lionized by the orthodox establishment.

By the latter 1930’s, however, Hansen became more cynical about all of it especially after the setbacks in 1937 and 1938. To his view, America had found itself with a structural problem far more intractable than might be cured by even pure Keynesianism. Prosperity and growth had come to the United States based on three factors in varying combinations throughout the 19th century: 1. territorial expansion; 2. population expansion; and, 3. technological innovation. The Great Depression, then, was the opening act of what would happen should all three run dry.

Obviously Hansen was wrong about the last two. Not only was there yet another revolution looming, the Baby Boomer generation lay just outside his self-limited gaze. The problem with all economists, especially Keynesians of the mathematical persuasion, it seems, is that they always seem to extrapolate in straight lines. History, however, is lumpy, messy, and most of all cyclical.

Summers’ view, then, is that Hansen was wrong only in timing. He said in April, “My thesis is that Hansen was a couple of generations too early but that the issues he identified can be a chronic problem for capitalist economies.” I could take a cheap shot here and point out how orthodox Keynesians, statists first and foremost, often sound like good Marxists with their guard down, but any free market adherent will immediately make the connection. The 21st century of secular stagnation is primarily demographics and innovation, or the lack of it, since territorial expansion is more than a century into nothing more than misapprehended academics.

To preview my argument: If one thought ex ante that there would a big increase in saving and a big reduction in investment propensity, then one would expect that interest rates would fall very dramatically. And so this fall in rates is consistent with a market judgment that the secular stagnation hypothesis is true…

In sum, the evidence of unusually stagnant growth is overwhelming, as is the evidence that there is a market expectation of extraordinarily low inflation and extraordinarily low real interest rates going forward.

Again, I agree that the evidence for it is overwhelming, but his argument for the cause proceeds from intentional blindness. While we can’t know if there is another baby boom perhaps just around the corner, we can at least analyze the state of technological innovation without all the trappings and bias. It is falsely asserted that innovation ceased and that great progress ended with the basis of the internet. In only the strictest sense does that observation apply, meaning in the real economy. The technological progress that brought us the modern “information age” was all developed primarily in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

In the meantime, while those advances were being harnessed into mature economic processes, overall innovation did not just end, it merely migrated. The most breathtaking and elegant leaps forward since then shifted from the real economy to the financial economy. This occurred in great part due to the internet and computer revolution; what has become of the eurodollar system would never have been possible without it. In some ways, with central bankers lulled into self-confident sleep, this was the next logical leap.

That was the history of the late 1990’s and especially the decade of the 2000’s. While the industrial economy in the developed world fell off, due to the eurodollar’s ascent in financing the industrial rise of emerging market production, it was replaced (badly; inefficiently) with financial innovation that leaked out in the form of debt, debt, and more debt. The end result of all that technological “progress” really was, in very simple terms, to find ways to increase the amount and level of credit far beyond any reasonable, traditional restrictive objections. It was the spirit and essence of securitization, for example, which intended to turn risky assets by piece into largely safe ones (from the mezzanines on down to the senior and really the majority super senior pieces) all so that the financial world would buy and absorb more of it. The eurodollar system’s role was to create the liabilities, in all their splendor and varied forms, to finance it all on both sides – consumption and production.

The BLS tells us unequivocally that the labor market fell off around the dot-com bust and never returned. For a brief period in the middle 2000’s, that seemed not to have mattered because the debt flow was so immense in this direction that the developed world could temporarily finance its own impoverishment. The eurodollar system was feeding the capex “revolution” in emerging markets while simultaneously financing the very customers (at the margins, which were by then unusually thick) that were supposed to support it forever more (it isn’t just orthodox economists who extrapolate in straight lines; sit through a financial presentation and see them everywhere). It was, as so many in the mainstream declared, global prosperity.

It was all an illusion, one that economists such as Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke felt but dismissed (“global savings glut”). Thus, the dearth of technological advance after the Great Recession, really starting August 9, 2007, was the unwinding of the monetary, eurodollar fantasy. It is so blindingly simple that even economists who have trained their whole lives for this, steeped over and over in the legend of monetary failure of the Great Depression, dead set against any and all “deflation” for those very reasons, should be able to see it and have been ready for it. Instead, they spend enormous time and effort to figure out why what should be readily apparent just can’t be.

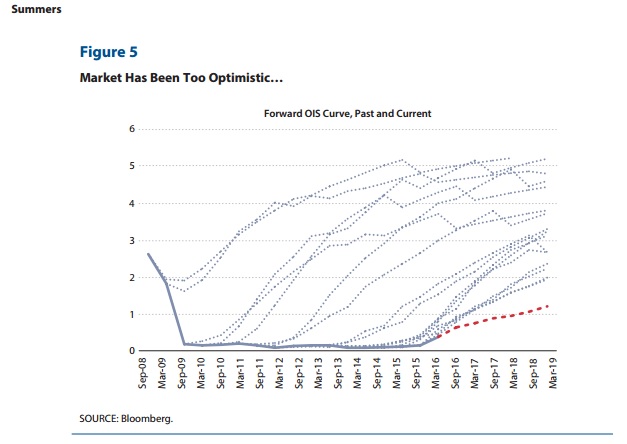

Which brings us to Dr. Summers’ chart:

OIS is the overnight index swap, and it is a money rate that policymakers hold very dear (though they shouldn’t, but that is another story). It is a fixed-for-floating swap anchored (typically in US$’s) fixed to the federal funds rate and floating usually to something like LIBOR. In general terms, it can measure both interbank credit risk and liquidity. During the worst of the panic, which was entirely an interbank affair, having never entered the payment system and actually threatening a Great Depression deflation scenario, the LIBOR-OIS spread jumped to nearly 400 bps. That fits the convention, where a high spread indicates illiquidity and risk/fear.

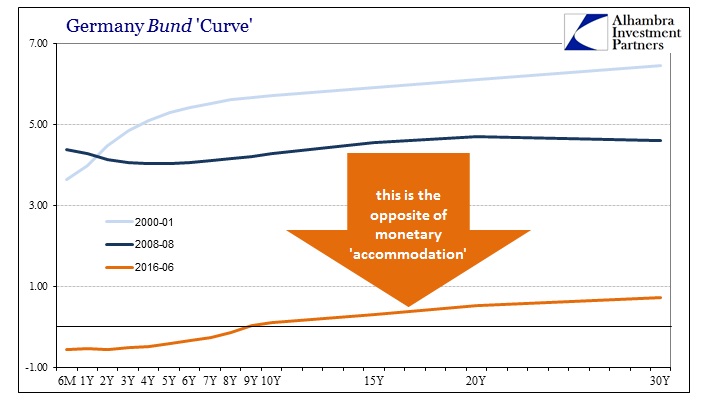

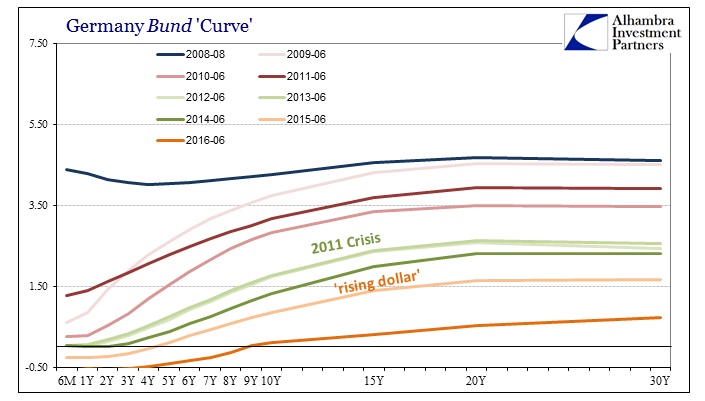

But the world on this side of the panic is in many ways upside down, falling as we have into what I noted yesterday of Milton Friedman’s interest rate fallacy. In a normal regime, a high spread indicates problems, but in an “ultra-low” regime the persistence of no spread shows us a lack of money growth and really the expectation for that to continue as each and every optimistic curve fails to be realized in the actual money market.

And in the same way, the view of the market has been that normalization is 6 to 9 months away and will take place at a reasonably rapid rate. And that has been the consistent view of the market since 2009. That view has turned out to be very overly optimistic when compared with what happened. And as overly optimistic as the market has been, the Federal Reserve has been even more so.

It speaks directly to the idea of “efficient markets”; how can money markets, the very basis of the wholesale financial system, continue to be so wrong? The answer is that QE and the view of bank reserves as money for use in the real economy is and has always been mistaken. Therefore, the upward sloping OIS curve (the one that finds normalization “always” 6 to 9 months into the future) is a bet on bank reserves as money; the eventual shriveling of it is the same as we find everywhere else, from German bunds to US treasuries to eurodollar futures – monetary contraction.

That does not, however, lead in the monetarist direction upon identification and realization; while I think the monetary causation largely unassailable I disagree about what that means. In other words, a monetarist would assume that the answer to monetary contraction is centralized monetary expansion, in this case properly done in the right place of eurodollars rather than idle, inert bank reserves, but that wouldn’t work, either. In short, it seems most likely that the solution is scrapping the eurodollar altogether and starting over with an actually stable platform; monetary contraction in this context seems permanent and that is why, so long as it is allowed to fester and continue by policymakers who deny it, I agree with the idea of secular stagnation as an end result. The global economy will not escape until monetary imbalance is rectified (which would likely also mean a related debt jubilee).

Why do economists keep denying the very conditions that they were intellectually raised for?

The contrast between what happened after the fall of 2008 and what happened after the fall of 1929 was a notable macro-economic achievement. Collapse and catastrophe happened after the fall of 1929 with the Great Depression. There was nothing like the Great Depression after 2008, in part because of aggressive actions of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury.

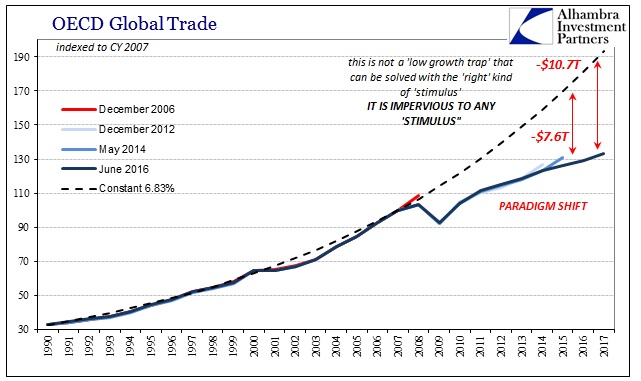

Because they are never wrong. They did everything that Keynes and Friedman said that was to be done, and it didn’t work (setting aside the highly debatable claim that “aggressive action” actually did any good at all); there is no recovery. In fact, another of Dr. Summer’s charts shows the absolutely drastic cost of this failure. If secular stagnation continues, we are on track to perform worse than the Great Depression:

Since these economists believe down to their very core that they did everything they were supposed to, and it was all expertly designed and carried out, the fault must then lay with the economy itself. It cannot be the slow strangulation of monetary contraction because Friedman, Bernanke, Summers, etc., have all studied the Great Depression ad nauseam and would never make, as they see it, the same mistake. Again, they have been this whole time extrapolating in straight lines, as if money in the 1930’s would be the same as money in the 1990’s, 2000’s, or now the 2010’s (when in fact the eurodollar system itself is already vastly different in 2016 than 2006 or especially 1996).

Contrary to the core assertion of this view of secular stagnation, there was indeed another innovative revolution that altered the entire world trajectory; only it was far more nefarious and misunderstood by economists, in particular, who had decided, while this revolution was occurring, they had learned everything worth knowing. One of the few great ironies of secular stagnation that is somehow comforting if still also infuriating is that the eurodollar standard, the world’s true reserve currency this last half century or so, will likely end before anyone even knows it was there. That includes all the world’s monetary experts.