The IMF released the first 2016 edition of its World Economic Outlook (WEO). Titled Too Slow For Too Long, it seems as if the institution has finally caught on to the fact that the global recovery never really was a recovery. Throughout the report you get the sense that they are starting to figure out what is going wrong but are prevented from recognizing the full extent by their ideological devotions. In other words, they are listening to the problem but cannot yet “hear” it.

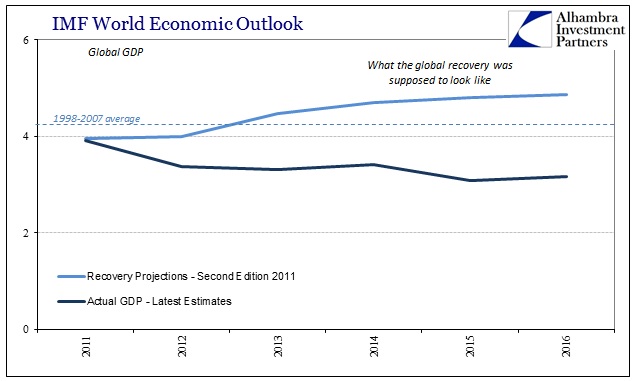

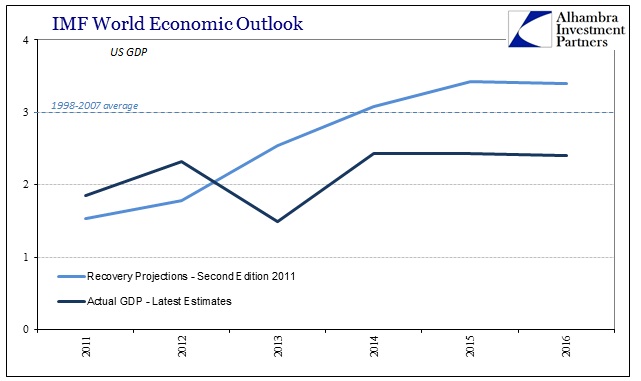

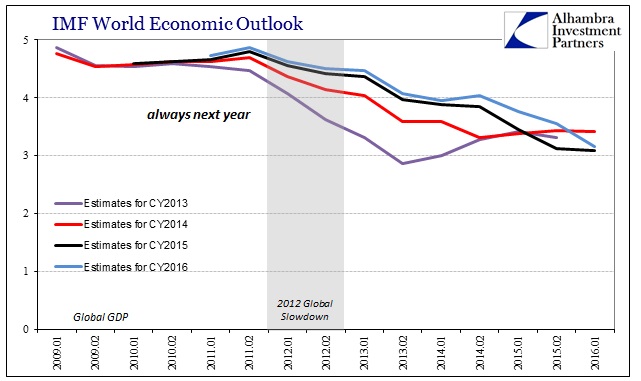

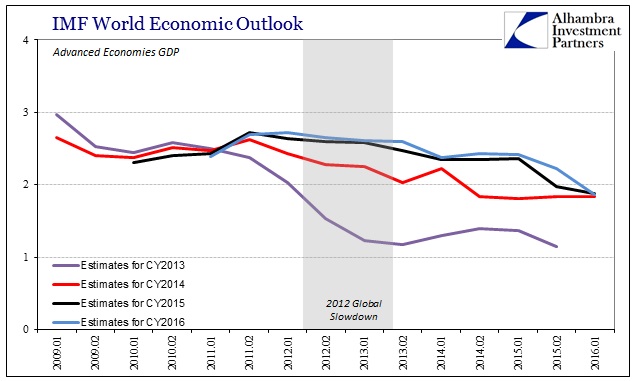

There is nothing in their updated projections that come as a surprise. It is the usual downgrade across-the-board in incremental fashion – the slow drip of the slowdown that is now unimpeded into its fifth year. Global GDP that was expected to be just over 4% in the second edition of the 2014 WEO is now cut to 3.16%. Estimates have finally given up on 3% growth in the US, as the “best” annual GDP prediction in the IMF series is now just 2.5% forecast for 2017 – and only down from there to what looks like a new estimated baseline of just less than 2% in the US. That is a huge discrepancy compared to the 3% average that existed between 1998 and 2007 (which, notably, includes one recession in that average).

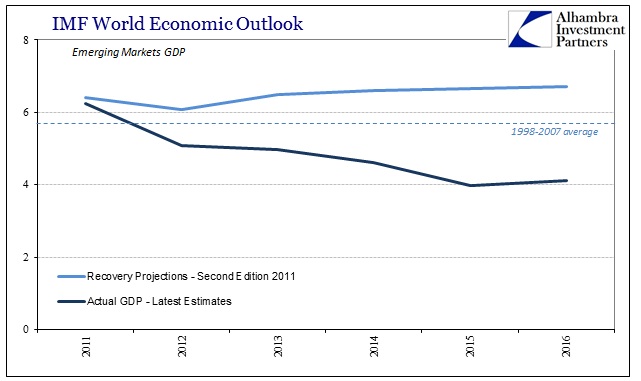

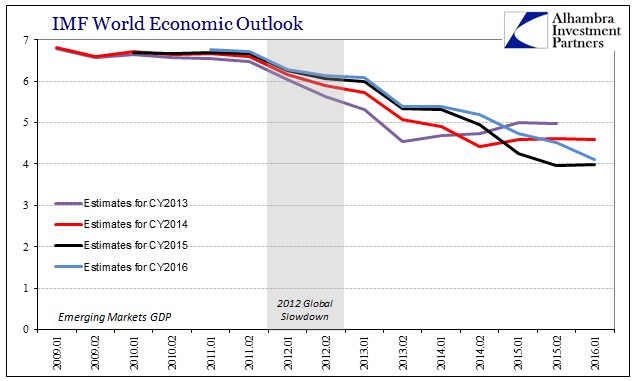

The biggest downgrade has to be, tellingly, economic growth in emerging markets. The average GDP advance in EM’s from 1998 thru 2007 was 5.8%, but the IMF now estimates that there won’t even be 5% growth again until 2020.

Charting the history of these forecasts and projections is quite revealing. Take, for example, what the recovery was supposed to look from the 2011 predictions against what it has occurred instead and you see nothing but steady slowdown where gentle but sustained acceleration was expected.

The 2011 Second Edition was released just as the US had completed QE2, the ECB had already begun “normalization” with not one but two rate hikes and the consensus was that the world would grow slightly above average in order to gain symmetry after the Great Recession. By all counts, the global economy should have followed that course since the economic hole at the start of the “cycle” was enormous. Thus, the very word “recovery” could only apply to those circumstances, where growth after the huge decline matched its intensity if not all at once then over time.

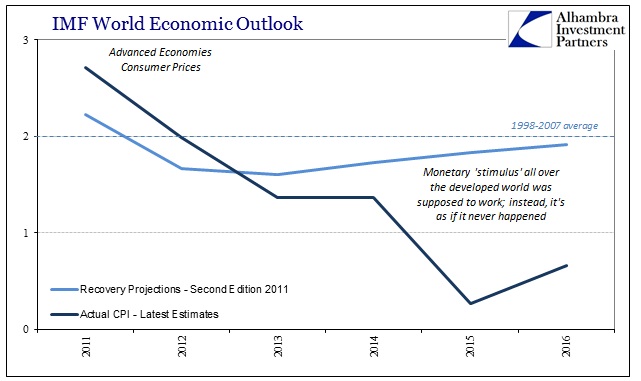

These particular set of projections also occur during the initial stages of what would become the 2011 re-flare of financial, funding, and banking irregularity that unfortunately revisited the global system. Therefore, what they show is what economists thought the world economy was supposed to do under “stimulus” that worked. Instead, global growth slowed after 2011 and has remained in that state no matter what central bank does what in any given place.

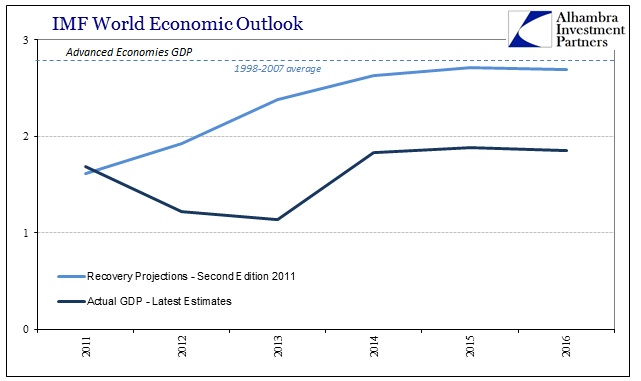

That much we can see in the advanced economies especially Europe, Japan, and the US. The slowdown in 2012 hit hard and those economies only modestly rebounded in 2014. The current set of predictions holds no more acceleration as the IMF has given into “secular stagnation.”

Another threat is that persistent slow growth has scarring effects that themselves reduce potential output and with it, consumption and investment. Consecutive downgrades of future economic prospects carry the risk of a world economy that reaches stalling speed and falls into widespread secular stagnation.

They do not immediately or explicitly list the cause(s) of “secular stagnation”; merely note its potential effects. That starts with, again, the fact that central bank “stimulus” remains conspicuously absent in the results quite opposite all prior expectations and promises. Thus, we can begin to “hear” that there is at least some monetary function amiss.

US GDP growth is no better now than 2011 or 2012, remaining more than 0.5% below its prior average. That may not seem like a big miss but it is, especially stretched out year after year (lost compounding) but more so in relation to again the size of the GR itself. There is something very wrong where you have a large contraction and then a continuously stunted growth period (not a recovery) thereafter. Economists have been using the academic idea of “secular stagnation” to avoid any diagnosis of why this disparity exists. By their own projections it should not have; it just suddenly appeared in 2012 as a durable (not transitory) redirection of the global and US baseline.

Before 2012, the IMF, as every other DSGE orthodox model, assumed that growth would be consistent and relatively robust year after year. After 2012, this annual ritual of incremental reductions to estimates took hold and hasn’t yet found its end. It is absolutely clear that “something” changed in 2012 that has manifested as this slowdown that forces only piecemeal admission of its existence.

The result in terms of GDP is not just the downgrade to projections of the “lost” half or three quarters percent in actual growth every year, it is the fact that those widespread reductions mean that there will be no recovery. The entire idea of a slowdown is difficult to process in any period, but following a large contraction it creates inordinate problems starting with financial imbalances – especially since so many financial and economic factors were put in place (and created) with the idea that the recovery would eventually show up and sustainable growth would soon to follow it.

The slowdown as an end to the recovery is much more than “secular stagnation” or even a slowdown; it is a paradigm shift that because it is being revealed slowly creates definite discrepancies in both function and interpretation. It isn’t recession so economists declare still growth and recovery even though downgrades persist and “global financial turmoil” has now accompanied them.

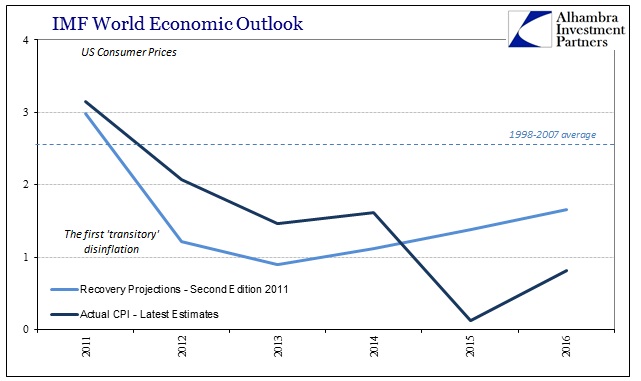

The biggest discrepancy to the recovery trajectory has been “inflation”, which further directs toward some monetary misalignment. In late 2011, the IMF forecast inflation in the advanced economies, including the US, would decelerate into 2012 after being well above target throughout 2011. It was thought that would be the natural adjustment to normalization where inflation over time would follow the recovery and gently accelerate into the “soft landing”, utopian future just under every central bank’s 2% target.

Instead, “inflation” started falling in 2012 and hasn’t yet stopped. The current forecasts for 2016 show a small pickup around the world, but it is still early in the year with plenty of time for more downgrades (as with current estimates for 2016 GDP, especially in the US if current Q1 forecasts hold at around 0.0%).

If monetary policy clearly left no momentum for advanced economies, emerging markets suggest the reason. The “developing world” is far more dependent upon global trade and thus global finance for its marginal expansion; especially in terms of marginal growth and motion of expansion. And it has been emerging markets that have seen the most persistent slowing yet.

Once again, 2012 marks separation from the recovery that was supposed to be and the end of the whole idea. Thus, we have advanced economies monetarily resistant to “monetary stimulus” during the same period where financialized economies downstream not only fail to achieve prior averages but also decelerate further under it. It is far more troubling here as the scale of the slowdown is much more significant leaving the financial imbalances that much more imbalanced.

In other words, the early “recovery” period financial “flows” were predicated on EM’s vastly outperforming DM economies especially given the sudden and “unexpected” “new normal.” Instead, relative to the continued slowdown in DM’s, EM’s have performed far worse after 2011; it was forecast at the second edition 2011 WEO that 2016 EM GDP would be a relatively healthy 6.72%, nearly 1% better than the 1998-2007 average. Obviously, that never happened but the current estimate for 2016 EM GDP is just 4.1%, more than a third less than the forecast.

Despite the recent rebound in asset prices, financial conditions in the United States, Europe, and Japan have been on a tightening trend since mid-2014, as the new Global Financial Stability Report documents.

Yet financial conditions have tightened even more outside the advanced economies. Increased net capital outflows from emerging markets…lead to further depreciation of their currencies, eventually triggering adverse balance sheet effects.

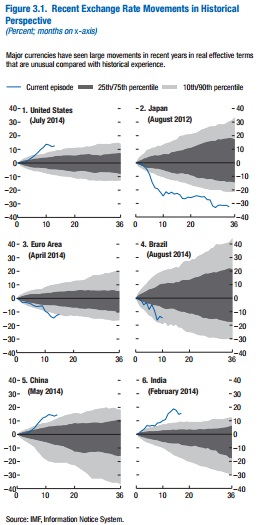

That suggestion is backwards, as the slowdown itself already triggered “adverse balance sheet effects” which we found as only more slowdown. The whole idea of “capital outflows” is 1950’s thinking, as there would have to be “capital inflows” somewhere else to balance what was set as an equation. Again, the IMF sees very well the financial irregularities without recognizing them as the cause. They even go so far as to note the historic, dramatic currency mess of the past year and a half (in the October 2015 WEO), but still insist on some mysterious and undefined “secular stagnation” pushing the global economy further and further away from recovery.

All the pieces for good analysis are assembled here in the WEO’s, only orthodox ideology prevents the institution’s economists from claiming it. By their own accounting, “something” happened around 2012 that pushed the global economy off the slow recovery track it was assumed global “stimulus” would deliver. In its place has been only an increasing slowdown that is impervious to further applications of monetary “stimulus”, measured at the start in both GDP accounts and official inflation figures. Furthermore, the slowdown has hit EM’s unexpectedly and much harder than the continued stagnation in DM’s. And to all that we find immense currency volatility especially since 2014 (when the slowdown entered its third year and started to convince many that the recovery was just never going to show up), commodity crashes, and increasing and repeating financial trauma.

In other words, it bears all the hallmarks and scars of the slow constriction of a monetary noose; the shrinking global money supply. The IMF “hears” secular stagnation even though they detail all sides of the eurodollar system’s ongoing decay because mainstream theory does not allow observation. Instead, orthodox economics only permits “what should be” even where “what is” could not be more apparent. That is why, even after five years of these downgrades and continual slowing, the IMF still predicts a turnaround (though less robust) just around the corner even though the trend is clearly entrenched. This is not an insignificant difference; at the end of secular stagnation is downgraded growth, but steady growth nonetheless. The final stage of a slowdown based on monetary decay and restriction is likely to be nothing like that.