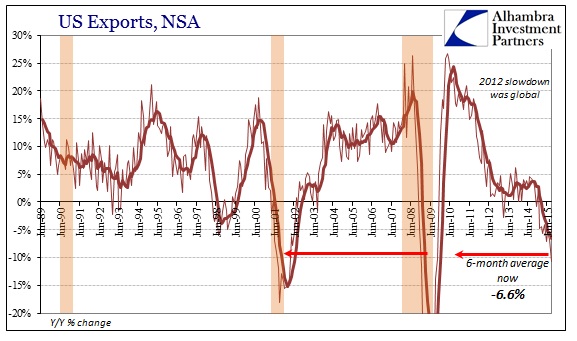

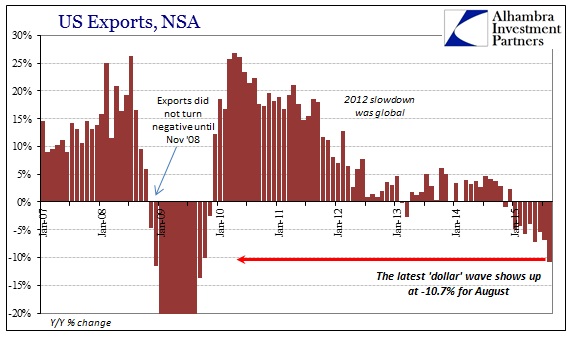

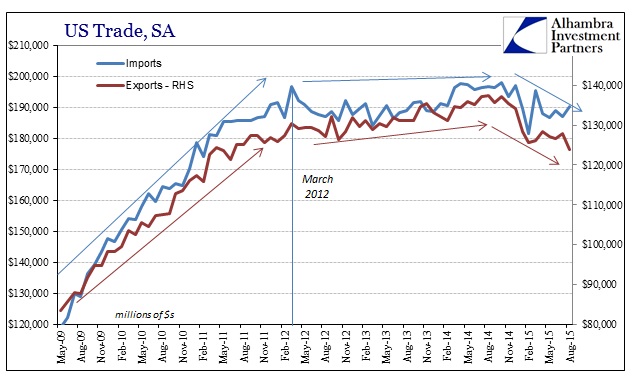

The Census Bureau updated US trade activity for August, with export activity dropping almost 11% year-over-year. The global economy is clearly falling apart, no matter how much economists wish to see the dollar (exchange rate fluctuations) where the “dollar” (wholesale finance pulling back leading to economic disarray) already is. Export activity is only a little short of the trough of the dot-com recession, having already significantly surpassed the entire first phase of the Great Recession and the worst of the Asian flu.

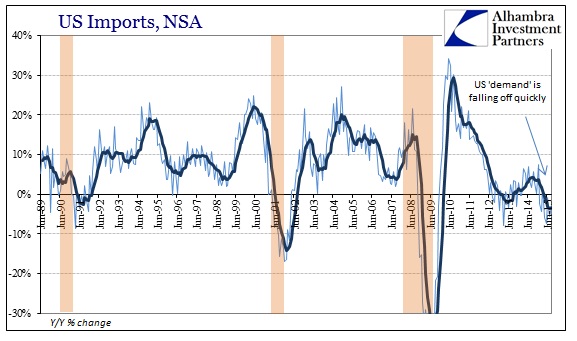

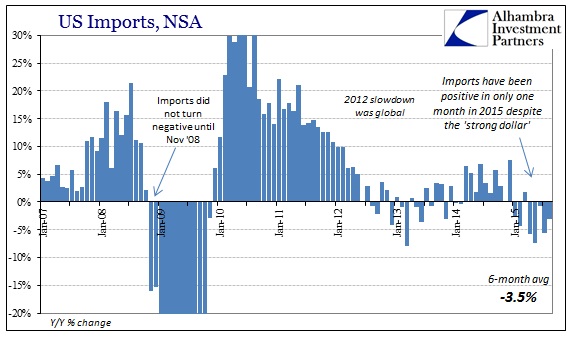

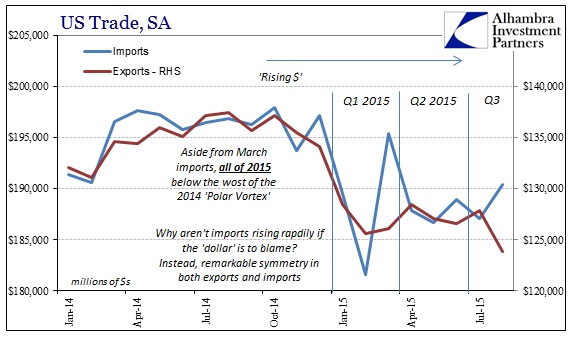

The state of global recession being rather well-known, it is thus the import side that is of the more relevant confession. As noted not long ago, the insinuation that the dollar would mean only overseas economic problems is disproven by the continued contraction in imports. The figures aren’t as immense as exports (yet), but the continuous decline in import activity more than suggests a conspicuous lack (to the point of contraction) of US “demand.” Outside of a barely positive reading in March (at the regular quarter end “bump”), US imports have declined in every other month this entire year. While July-August was slightly better in comparison to April-May, that, again, suggests the lagging US response to the “dollar” waves.

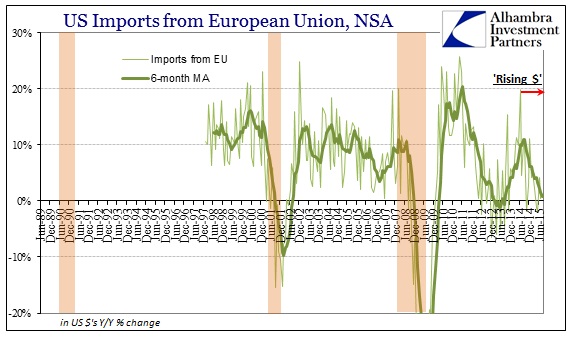

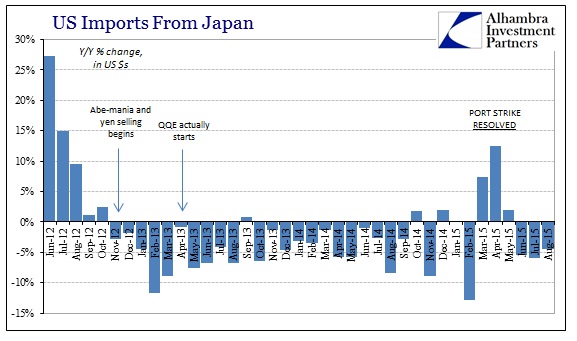

US imports have not surrendered by this much for this long outside of recession. Worse, the slowing and sinking in imports is taking place in the very jurisdictions (Europe & Japan) that have seen their currency exchanges grow the most “favorable” to US buyers. Undoubtedly, there are price adjustments to be made from these, but none so great as to come close to explaining the sharp slowing and contracting.

The direct effects on Q3 GDP will be highly negative, as the disparity between exports and imports is once again significant – though it isn’t quite clear as to how the seasonally-adjusted import estimate for August ended up positive. The adjusted series for imports is far more erratic than exports, so that might explain the difference similar to March (factoring out the port strike resolution). In any case, the economic “slump” or “hole” that is obvious in US trade extends “unexpectedly” in both trade directions and yet another month in time.

It is that view, I believe, that links the September payroll report to changing perceptions about the US’ place in the global economy. Even if you think the US isn’t under internal strain of its own, it is increasingly difficult to assert that it won’t at least be knocked off stride by seriously deteriorating trade activity in all directions. The congruity between this view of global “demand” and the following commentary (from the New York Times, no less) is this troublesome harmony of global recession potential:

The new numbers are poor on pretty much every level. American employers added a mere 142,000 jobs last month, far below the analyst forecast of 201,000 or the average over the last year of 229,000. Revisions pushed July and August numbers down substantially. The unemployment rate was unchanged at 5.1 percent.

This is usually the point in one of these stories where we would list the silver linings — the countervailing details that suggest it isn’t as bad as all that. This report doesn’t really offer any. Average weekly hours fell. Average hourly pay was unchanged. The number of people in the labor force fell by 350,000, and the number of people who reported having a job fell by 236,000.

We don’t even have a major snowstorm or other weird weather event to blame, nor a strike in a major industry, nor some outsize shift in the results from one category of employer that might suggest an aberration.

You know it’s bad when the mainstream has to stretch to justify the recovery narrative intact; it is something likely much worse when they no longer try as hard.