While the election confirmed the economic perspective of workers and small businesses, in a lot of ways big business has seen nothing different. In fact, apart from monetary-driven incentives, the two views of dysfunction are very much linked.

While profit gains have generally been solid, many blue-chip companies are posting weak sales growth or outright year-over-year revenue declines, causing worries about their long-term growth prospects. Others are reporting earnings increases driven by factors that don’t reflect sustainable improvements in their business, such as share buybacks and cost-cutting efforts.

Amplifying those concerns is a softening global economic outlook. U.S. multinational firms are now contending with slowing economic growth in key markets like Europe and China, and a strengthening dollar that threatens to further damp revenue by reducing the value of payments collected in foreign currencies when converted into dollars.

Companies that aren’t growing on the topline are going to be inordinately focused on their cost structure. Thus, despite the appearance of certain economic accounts, as companies struggle with revenue labor will struggle with wages and the actual reality of jobs and payrolls. There isn’t any fancy “economics” or statistics needed as that is just basic common sense.

As nominal wages have been flat since the “recovery” began, price changes and perceptions of instability about those price changes work against the economy (not for it as the orthodoxy expects). No matter how you look at the employment market, there is little to show actual acceleration or expansion.

Even the latest estimates of unit employment costs are more concerning than conforming. With wages stuck at 2%, the increase in total employment costs are coming from benefits, particularly healthcare costs. You know where this is heading, especially if revenues consistently fail to live up to something more resembling sustainable growth.

Revenue at S&P 500 companies is on track to grow 3.8% from a year earlier in the third quarter, down from 4.4% in the second and below the 4.8% average of the last five years, according to FactSet. Investors are left wondering how much deeper companies can cut and still wring out further expansion in earnings.

To put that in comparison, revenue growth is typically 7-10% Y/Y; and as WSJ spells out, the last time stock prices were as expensive (my word) as now, revenues were growing at 7%, not 3.8%.

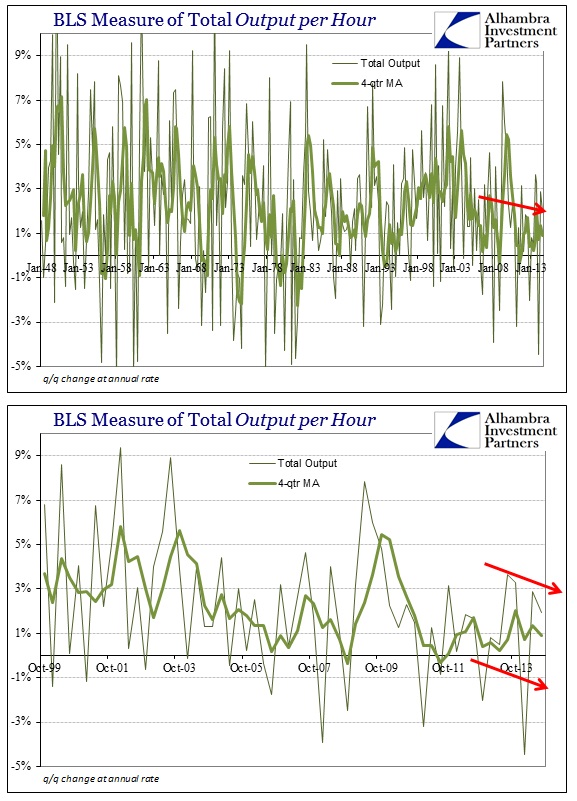

However, this labor problem predates the Great Recession. Going back to the 1990’s, employee output has barely been increasing which means that companies are not actually gaining too much benefit from labor resources (belying, somewhat, the statistical inference of “productivity”).

This one measure of productivity more than suggests that there is little for additional labor to work upon, and that labor is actually and already more costly (in these relative terms) than might otherwise be suggested elsewhere. That would explain in good part the reticence of businesses to add significantly to labor utilization (as well as lack of revenue growth, which again fits together).

In other words, all of this is another way of saying “secular stagnation.” Orthodox economists will puzzle over its causation because that’s what they do, but there is no real mystery here. Financialization is a penalty and the longer it goes the more the economic foundation erodes. This is attrition no matter what your own personal perspective.

Perhaps the biggest attrition for the Democrats has been among middle-class voters employed in the private sector, particularly small property and business owners. In the 1980s and 1990s, middle- and working-class people benefited from economic expansions, garnering about half the gains; in the current recovery almost all benefits have gone to the top one percent, particularly the wealthiest sliver of that rarified group.

That is the rarified work of serial bubbles, presenting an “answer” to not just more than a a decade of economic dissatisfaction but also the political football of “inequality” and rising Marxists. Bubbles were never a full part of Keynes, but that does not mean they are inconsistent with Keynesian means to achieve the ends of activity for the sake of activity. Resources allocated and conducted under these strained conditions is never going to be efficient enough to maintain a healthy potential trajectory let alone actual economic reality. As William Galston (also writing in WSJ) noticed all the way back in September, previewing electoral distance and elitist misanthropy:

More than five years after the official end of the recession, the Public Religion Research Institute finds, only 21% of Americans believe the recession has ended.

That is a nod not just against the recovery idea but how the “rule of bubbles”, serial as they are apparently now, is corrosive. What makes these results (everything contained here, not just the surveys) more alarming is that this all is taking place in 2014 amid record stock prices, an appearance that reaches into every single variable in this tattered orthodox equation.