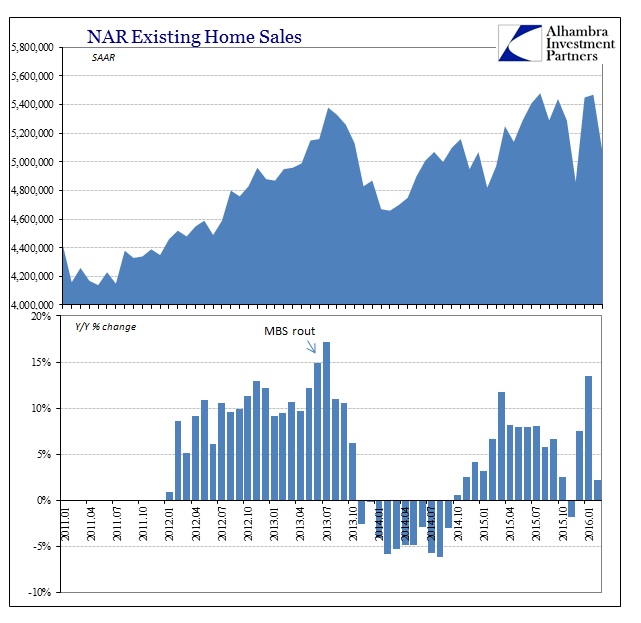

Existing home sales as reported by the National Association of Realtors fell 7.1% in February 2016 from the month before. It was a very large decline but followed a two-month surge beginning December 2015; which itself came after an unusually large decline in November. In other words, housing and home sales seems to be that much more volatile of late. That much is plainly obvious when comparing home sales since 2013 with the much tighter and more disciplined mini-bubble trend from before the “taper” selloff in the middle of 2013.

Reading through the NAR’s accompanying press release and really Chief Economist Larry’s Yun’s commentary, one is struck by how nothing seems to have changed. Here is Yun last year in March 2015 describing that February disappointment:

Severe below-freezing winter weather likely had an impact on sales as more moderate activity was observed in the Northeast and Midwest compared to other regions of the country…

With all indications pointing to a rate increase from the Federal Reserve this year – perhaps as early as this summer – affordability concerns could heighten as home prices and rents both continue to exceed wages.

Here is Yun today:

Sales took a considerable step back in most of the country last month, and especially in the Northeast and Midwest. The lull in contract signings in January from the large East Coast blizzard, along with the slump in the stock market, may have played a role in February’s lack of closings.

The overall demand for buying is still solid entering the busy spring season, but home prices and rents outpacing wages and anxiety about the health of the economy are holding back a segment of would-be buyers.

Weather is an ongoing theme for February sales, as if winter in the Northeast and the Midwest is winter. Here is Yun in April 2014:

With ongoing job creation and some weather delayed shopping activity, home sales should pick up, especially if inventory continues to improve and mortgage interest rates rise only modestly.

I only note the ongoing appeal of snow for very slight comic value, instead it is this “tight supply” idea that demands further inquiry. What Yun wrote in 2014 was correct in that if jobs were truly expanding and inventory improved then home sales should have been more sustainably robust and far less volatile especially of late.

There really should be stronger levels of home sales given our population growth. In contrast, price growth is rising faster than historical norms because of inventory shortages.

Two years later, inventory continues to decline. That has had the effect of squeezing prices higher and out of reach for far too many, leaving them to depend on the whims of the FOMC (and really the 10-year UST yield since monetary policy is almost irrelevant) for holding mortgage rates. This makes no sense under the conventional narrative, as rising prices and gaining economic momentum should lead to increasing inventory, or, at the very least, the level of unsold homes rising to match overall sales.

Instead, starting last summer, the amount of inventory began to decline so that by December the non-adjusted ratio of “months supply” was less than 4.0 for the first time in a very long time. In other words, the “inventory shortage” that was apparent as far back as March 2014 has only increased despite rising prices and overall more favorable (according to the NAR) contract terms (35% of homes, for instance, were on the market for less than a month). People just don’t seem to want to sell their houses and move somewhere else.

There are financial imbalances to also consider, including those induced by monetary distortions provided to the housing market as “stimulus”; especially the rush of investor funds to buy up low end housing (foreclosures and distressed) to convert into rental units. The Fed didn’t care who was buying or what that might do to the overall economic balance in housing (Keynes, after all) so long as anyone was. The real estate outfit Trulia suggests in its housing data that these imbalances are significant factors limiting “supply”:

Trulia attributes the reason for the low inventory in starter and trade-up homes to a combination of factors, including the number of foreclosed homes that were bought by investors during the recession and turned into rentals.

The current high cost for premium houses also plays a role. As prices for premium houses rise, it becomes more challenging for buyers looking to trade up on their current property to find an affordable home, which in turn makes them disinclined to sell. The Trulia study reports that the cost of premium homes has increased by about 20.3 percent since 2012.

The gap was similarly high in the mid-2000’s but wasn’t so much a problem then because of bubble mechanics as well as different economic reality (or perceptions). It is the combination of those that seems to be limiting and squeezing the housing market into something unrecognizable to what should have been fundamental, organic growth had the Fed left it (and the economy) alone. A great deal of the housing flow is stagnated on jobs that are supposed to be having an effect but “somehow” aren’t and the artificial imposition of gaps between segments – the bifurcation of markets as well as the economy. Those that are doing well in this split, redistributionary circumstance have done really well, only making it that much harder for the rest to catch up, let alone join.

It seems in that sense the housing market is a microcosm of the Fed’s QE economy, where “stimulus” is that only in the narrowest sense of causing disturbances that might appear greatly dissimilar to contraction. That is a far different prospect, however, than a true and balanced recovery which is required for sustainability. In that sense, it is difficult to blame those reluctant to engage despite basic economics that demand they should; prices are rising but more so in where people want to go than in what they have, and they are to base taking on those yawning price risks upon economic prospects that never quite seem to come close to matching the mainstream rhetoric and now look even shakier.

In other words, in light of QE-math, years of “tighter inventory” makes perfect sense.