Nearly all (97.5%) of the S&P 500 companies have reported for the first quarter. EPS for the index companies stumbled rather spectacularly, though weather is being blamed for nearly all of it. Back on January 23, index EPS in Q1 was expected at around $29.40 (as reported). As of the latest update, EPS is only at $24.79, a 15% miss in just over four months. That means such massive over-optimism wasn’t just reserved for the retail industry. And it wasn’t just GDP that took “everyone” by surprise.

I think the major part of the problem is that the current state of business and the economy actually looks caught in between what would be considered “normal” growth and function and recession. As such, there are elements of both incorporated that muddy and muddle analysis, at least on the surface.

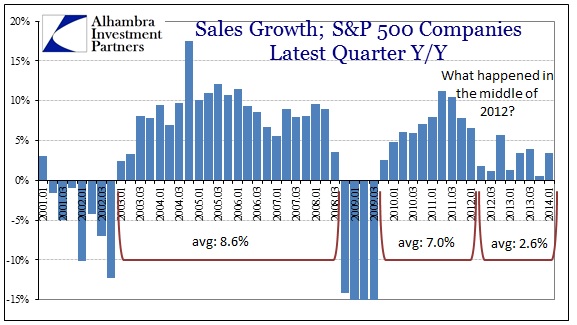

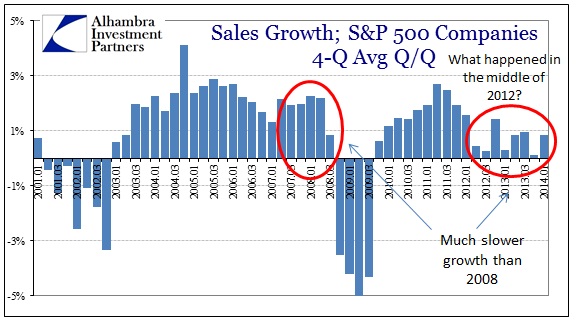

Appealing to meteorology fits within that confused state, because if you see recent growth as tepid but not recession (glass half full) than an “exogenous” explanation like polar winds and half blizzards fits within that perception. But it still does not explain the clear chasm that opened in the middle of 2012.

So the economy clearly slowed down at that point, but did not turn toward what would look like historical recession. Worse, because this period has elongated and persisted now for two years, it doesn’t lend itself as easily to interpretations about future direction. On the optimistic side, there is recency bias and a fair bit of circular logic – no recession showed up in the past two years despite this slowdown, so no recession will show up since it is just a slowdown.

A good part of that analysis lies in believing in the concept of efficient markets. If you believe in some stronger form of efficient markets, stock prices are telling you that this is a slow patch to be endured temporarily, and that the recovery is coming, and robustly so. Since prices are determined by the trading of a lot of very smart people (and those that follow closely these smart people), and there is no doubt about that, then prices are discounting the future. The cumulative action of market determination would not, under efficient market hypotheses, be led so astray.

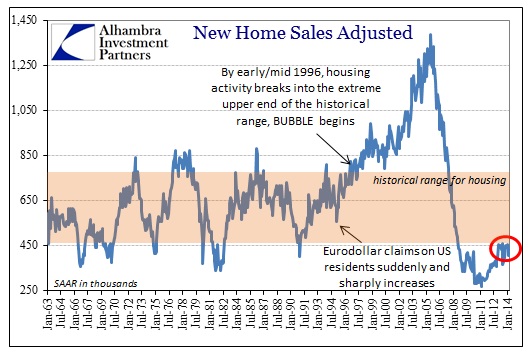

Anyone with a healthy appeal of skepticism sees it quite differently, particularly in light of not just the past but the very recent past. What were stock prices telling us about the economy when the S&P 500 hit a record high in October 2007? The eurodollar market had already froze nearly completely, liquidity fragmentation was already a serious problem and slowing had been evident in the real economy for nearly a year by then. Furthermore, what were the ridiculous valuations of the late 1990’s telling us about the growth prospects of the 2000’s? Nothing very valuable in both cases.

So, if you think the stock market is full of very smart people who would only make reasonable bets as a discount to future expectations, you tend to believe that current caution and bearishness is way, way overdone (nothing bad has happened and it’s been five years). If, however, you think that those very smart stock investors have been captured in a fashion not unlike a cult, then their bets devolve not into discounting the future but into self-fulfilling and reinforcing expectations for each other’s willingness to keep on betting. The former scenario is what everyone is taught about stocks, the latter describes the world of finance after interest rate targeting, at least in my opinion. The difference between them is where bubbles are made.

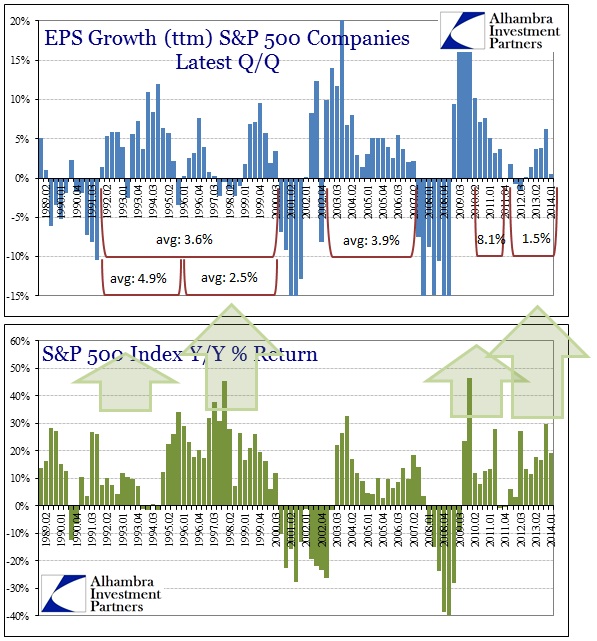

If you synchronize earnings growth with market returns that shows up rather clearly. EPS in the early part of the 1990’s was far stronger, yet market returns were much more “average” and unspectacular. Yet, earnings in the late 1990’s were far less vigorous and much more volatile, but something changed in the market’s reaction to it. You really don’t have to look far to find a culprit, as even the smartest investors will have trouble discerning positions with systemically rigged prices – artificial setting of the price of risk interrupts the very basic self-regulation mechanism of true markets.

That was/is true of more than just stocks.

What I see now in stocks is much the same setup, though condensed by circumstance. Earnings were far stronger and regular in the first part of this “recovery”, and stock prices did react to them. Now, like the latter part of the 1990’s, earnings are much less robust and more volatile, but prices are even more assured of themselves. I think, again, that comes down to the cultish rationalizations for these kinds of markets. And that applies equally to observations about the economy – where slowing does not indicate a temporary setback but rather a decay with a different slope than we are used to.

That really shouldn’t be so surprising given the massive confusion in markets and elsewhere, particularly under the immense and determined persistence of intrusion and manipulation by command and control policies.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@alhambrapartners.com