There is an undoubted shift in the behavior of consumers, including and especially during the peak retail season between Thanksgiving and Christmas. However, to say that is the sole reason for the decline in actual sales volume is to stretch that truth into (in many cases intentional) utter misdirection. The initial indications from the retail outlets are so far beyond bad, worse than even last year’s decline.

In other words, the same excuses are being made in 2014 that were also used for 2013; yet for all the changing guard toward the internet, sales last year still came out, overall, as the worst holiday season since the Great Recession. That is the mark and standard for disingenuous appeal, and to see it used once again against a greater decline shows there is a far too much denial being spent on maintaining the “narrative.”

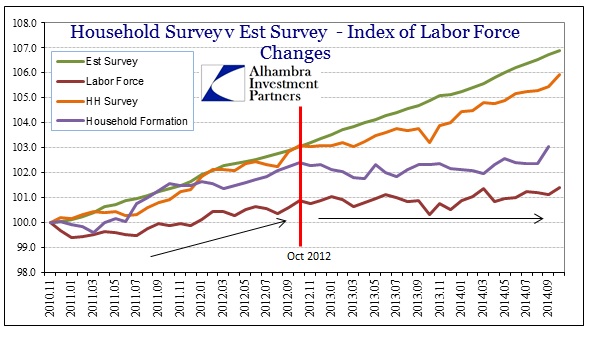

That is what it really comes down to, as all the mainstream commentary, derived from credentialed “experts” on nothing more than statistics, says the economy is gaining traction and getting demonstrably better. The problem is that such “demonstration” is terribly limited, contained only to the most adjusted of economic accounts like GDP (and only intermittently) and the Establishment Survey. But because GDP was good the past two quarters and the official unemployment rate is falling, and quickly, retail sales cannot possibly be looking more and more like recession.

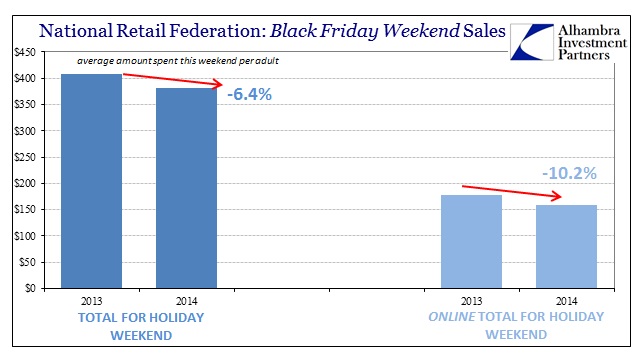

In simply holiday sales alone, what happened during Black Friday was not anomalous at all, but rather all too representative of what was to come. It is simply too much to suggest both a growing decline and the timing of it as largely innocuous spending patterns inside an otherwise very healthy economy. There is nothing healthy about this, especially as it captures the movement of spending online:

The estimated amount of spending this weekend, per adult surveyed, fell 6.4% according to the retail industry’s own trade group. And belying the shifting consumption pretext, online spending fell just over 10%!

Even after doling out discounts on electronics and clothes, retailers struggled to entice shoppers to Black Friday sales events, putting pressure on the industry as it heads into the final weeks of the holiday season.

Spending tumbled an estimated 11 percent over the weekend from a year earlier, the Washington-based National Retail Federation said yesterday. And more than 6 million shoppers who had been expected to hit stores never showed up.

Consumers were unmoved by retailers’ aggressive discounts and longer Thanksgiving hours, raising concern that signs of recovery in recent months won’t endure. Retailers also were targeted by protesters, who called on consumers to boycott Black Friday to make a statement about police violence. Still, the NRF cast the decline in a positive light, saying it showed shoppers were confident enough to skip the initial rush for discounts.

That last sentence says a lot about how far the “narrative” has to shift to try to make sense of reality while still maintaining that the economy is “gaining.” The NRF is attempting to use the inverse of the Japanese experience – Japanese spending surged ahead of the tax increase because the economy was already in trouble; US consumers in this robust economy did not show up (despite the prior expectations that they would) because they didn’t need the discounts. That might be plausible (and only slightly) if there was any indication at all that consumers were in great shape beforehand whereas Japanese consumers were very much in trouble prior to the tax change. There is simply nothing other than statistical models that pre-judge monetary “stimulus” to suggest consumers are doing so well that they are now staying away from Black Friday in droves. Instead, this “unexpected” decline, to convention, is perfectly consistent with everything that has taken place this year.

In fact, if you look at the past six Black Friday weekends, there is that same discernable pattern than has been included in almost every other economic account. It is not “unexpected” at all to see that Black Friday spending peaked in 2012, especially since so many indications of consumer health (including alternate payroll estimates, as well as labor participation and even household formation) changed trajectory, or even stopped rising, right around that time. Spending is now down not just two years in a row, but to levels below even 2011!

Again, there is no doubt that there is an ongoing shift in consumer spending behavior toward online and even other days and weekends of the holiday season, but that is only a partial factor. The serious erosion, attrition really, in spending is rather the continuation in the elongated cycle descent. The more that carries on, the more convoluted the attempts to wish it away.