The Bank of Japan had previously “disappointed” last December when it failed to announced more “stimulus.” Setting aside who might actually have been frustrated by the lack of renewed distortions, the Japanese central bank did make some minor alterations to its QQE regime at that time. They expanded the list of eligible collateral and extended the average remaining maturity range for their intended JBG purchases. It was also announced that QQE2 would now include ¥300 billion in new ETF purchases.

That latter sounded initially like an expansion in both Q’s (quantitative as well as qualitative) but to make room for the new ETF’s the Bank of Japan would restart selling equities that it had purchased from banks in the early 2000’s in order to keep the net level of holdings equal. That raises several questions, including what did those purchases accomplish that they can be sold finally, what good might have come out of holding those assets for so long and really what was the point?

When Haruhiko Kuroda announced yet another scheme on January 29, this time a tortured negative rate policy, he remained devoted to the same platitudes that were issued by his predecessors who first purchased equities and JGB’s a conspicuously long time ago.

The reduction will cause real interest rates to fall, with the goal of stimulating consumption and investment, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda said in a news conference in Tokyo Friday. The new policy will push down rates for lending, although it won’t have a negative impact for banks, he said.

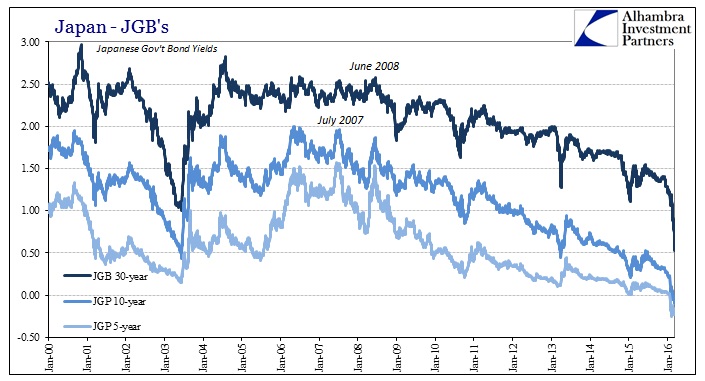

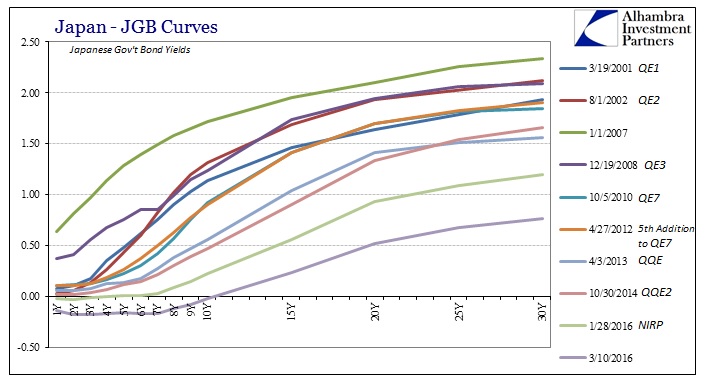

The various QE’s especially after 2008 might have had that intended effect on at least “push down rates”, though for the size and persistence of continuous QE you would expect to find a more determined correlation. In fact, JGB yields started declining on economic concerns in 2008 two years after QE1 & 2 had been shut down and months before the beginning of QE3 in mid-December 2008.

With Japan only into and out of recession the entire time between then and now, how much of the “death of money” shown above is QE/QQE and how much is the possibility that Japan has yet to really come out of one big, continuous recession? The tailing of yields at the far right, the most recent trading, is undoubtedly related to NIRP but that is only in the fact that Japanese banks are forced by it to seek out another form of liquid, risk-free. In other words, the precipitous drop in JGB yields of late already suggests how NIRP is already failing.

Let’s assume, however, QE in all its forms is responsible for interest rates as shown above. In order for the Bank of Japan to have accomplished its intended task of “pushing down rates for lending” has meant the absolute destruction of money curves. The scale of this repression is enormous, and in that context it really doesn’t matter whether it was due to the Bank of Japan or the Bank of Japan’s failure. We begin to see why NIRP has no effect, as with such depression in money time premiums there is absolutely no basic incentive for risk taking. Liquidity premiums, as Keynes once suggested for the real economy, rule here under the wholesale format.

If banks are to be charged for holding otherwise useless bank “reserves” then they simply find and use the nearest equivalent – even if that means a 30-year JGB bond which is only “risk-free” insofar as the Bank of Japan keeps buying it.

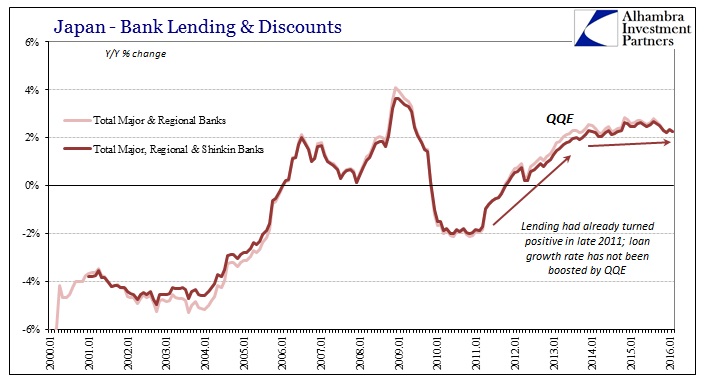

For that massive distortion, lending in Japan bears little to no resemblance to the destruction of money. You can make a weak case that there is some relationship between the QE’s and bank lending, but much less so as lending relates to interest rates.

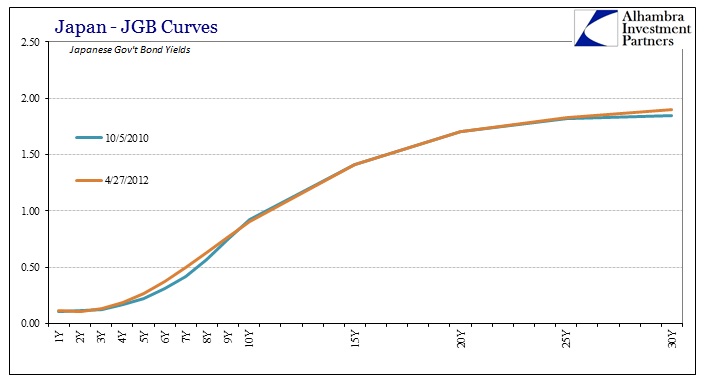

Was it the four additional QE’s (and expansions among them) that turned lending positive in late 2011? Perhaps that was just the natural turn after having declined for several years, especially given the events of 2011 with the earthquake/tsunami. The latter seems far more likely given that no matter the QE’s at work there really wasn’t much effect even on the JGB curve during that time.

Monetarists will argue that the return to positive lending growth was then due in some part to “portfolio effects” of the various QE’s, meaning that as the Bank of Japan purchased financial assets from Japanese banks they were forced elsewhere, including lending. That may have been the case, and was likely the case in some circumstances, but it still doesn’t add up to what proponents suggest. There is the unresolved matter of constant recessions in Japan, meaning that bank lending doesn’t seem to demonstrate the clear economic effects and transmissions as expected by QE theory. Beyond that, an increase in Japanese bank lending doesn’t necessarily mean an increase in bank lending in Japan.

From May 2014:

Japanese banks, meanwhile, are awash with cash—the result of the Bank of Japan’s efforts to channel money into the financial system by buying bonds. And making money from holding government debt, a conservative strategy popular in recent years, has become less certain as yields fall and inflation picks up.

Instead, banks are looking to lend more overseas to boost profits, especially to the fast-growing economies of Southeast Asia.

“Asia will be the center of our business given its growth potential,” said Koichi Miyata,Sumitomo Mitsui’s president.

Again, that was May 2014. If ever there were a more clear-cut case against QE in purely financial terms, this would be it. It is a damning commentary on economic prospects in Japan as well as these grand distortions that central banks undertake. Pushing Japanese banks through “portfolio effects” into the rest of Asia, and undoubtedly China, in 2013 and 2014 is being revealed in 2015 and 2016 as the worst possible move. Given what we know now about the financial conditions in the rest of Asia, liquidity preferences among Japanese banks under NIRP make even more sense once aligned to the twisted nature of monetarism.

The theoretical flaw is stated outright by the Bank of Japan in its statutory “Price Stability Target” currently set by policy at 2%.

The Bank of Japan Act states that the Bank’s monetary policy should be “aimed at achieving price stability, thereby contributing to the sound development of the national economy.”

Price stability is important because it provides the foundation for the nation’s economic activity. In a market economy, individuals and firms make decisions on whether to consume or invest, based on the prices of goods and services. When prices fluctuate, individuals and firms find it hard to make appropriate consumption and investment decisions, and this can hinder the efficient allocation of resources in the economy. Unstable prices can also distort income distribution.

“When prices fluctuate” counts more than just consumer prices as does that last sentence, “unstable prices can also distort income distribution.” Business and individuals react to financial distortions as much as consumer prices. In a highly financialized economy, that has only been allowed to be more so, financial prices might actually matter more. So the Bank of Japan in order to foster “price stability” has undertaken the intentions to sow nothing but massive instability in financial prices and all for very basic assumptions that don’t hold up well in a complex system. Economists assume that finance and economy are completely separate except for very well-defined and predictable channels of interaction.

Even the academic literature on QE is at best dubious. Among the most charitable of recent studies (2012) still can’t find much of an economic effect for the obvious asymmetry of all that financial disruption – in other words, assuming that the collapsing curves are actually traced in good part to the QE’s, so what?

Using a structural VAR model, the paper finds some evidence that BoJ’s monetary policy measures during 1998- 2010 have had an impact on economic activity but less so on inflation. These results are stronger than those in earlier studies looking at the quantitative easing period up to 2006 and may reflect more effective credit channel as a result of improvements in the banking and corporate sectors. Nevertheless, the relative contribution of monetary policy measures to the variation in output and inflation is rather small.

To which economists suggest and claim that it is better to undertake these massive interventions that might only accomplish “small” variations in output and inflation than do nothing. But that claim is based on a lie; namely that QE or QQE or NIRP are all neutral. In other words, all else equal (as economists model) even if QE fails it doesn’t create harm. We know that is false in the real economy especially in Japan by direct count of Japanese households. I suspect, as noted above, that Japanese banks are also being forced to reckon with the financial complications of “portfolio effects” which has left them, likely, very far from neutral vs. QQE or not QQE.

Monetary proponents keep implying that monetarism hasn’t worked because of execution (must be bigger or buy different assets) or even exogenous factors beyond their control. It is much simpler than all that because the basic assumptions that lead monetarists into something like QE don’t stand the slightest scrutiny. It is an academic concept full of ceteris paribus that barely survives first contact with the complexity of the real financial system, let alone the real economy. And even for all the “good” that it might do (and it is entirely debatable whether inflation targets are even a good thing to begin with) QE is left in place only because economists and policymakers refuse to accept even the most obvious costs to the distortions.

Under the most basic terms it never made sense anyway – fostering price stability by completely destroying basic pricing mechanisms. Honesty in reporting on it (stop calling it “stimulus”, for one) would have ended it long ago.