It makes for quite the juxtaposition, though perhaps not so jarring given that global banks are still enormous and disparate operations. On the one hand, Citigroup’s CEO was eminently confident from within the confines of Davos and the status quo:

The market is “adjusting” to a series of headwinds that can be overcome, Citigroup CEO Michael Corbat said Thursday, a day after theS&P 500 fell to its lowest level in nearly two years.

“We view what’s going on really as more a repricing than any big fundamental shift,” he told CNBC’s “Squawk Box” at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

The question is who is the “we” to which he is referring? It was just a year ago that no bank would even contemplate the possibility of recession entering Janet Yellen’s perfect year, especially as it was setup by “unquestionable” growth in the middle of 2014 (best jobs market in decades). This January, however, while Citi’s CEO downplays recent turmoil, the staff inside his very own bank is thinking very much otherwise:

The global economy is on the brink of a recession, with central bank stimulus less forthcoming and growth weakened by the slowdown in China, Citigroup warned on Thursday.

The bank cut its 2016 global growth forecast to 2.7 percent from 2.8 percent and slashed its outlook for the U.S., U.K. and Canada, plus several emerging markets including Russia, South Africa, Brazil and Mexico. [emphasis added]

That’s a lot of slashing in order to be so sanguine. I don’t agree with the premise, namely that this is all or even mostly due to China (the Chinese sell their industrial production to whom?), but the condition of the Chinese economy offers more universal interpretations upon these kinds of circumstances. That starts with the idea that China is slowing but within a more cheering transition to consumer rather than investment-led activity and margins. It is this idea that manufacturing and production matter, but not nearly as much as they used to and thus not enough to make a full recessionary difference right now.

After some minor encouragement in December, industrial factors in January have turned (yet again) to the depressively concerning. Today it was industrial profits.

Profits earned by Chinese industrial firms in December fell 4.7 percent from a year earlier, the seventh straight month of declines, as the slowing economy hits sales and forces many companies to cut prices to win business.

The weak performance is bound to spark fresh concerns about investment cuts, job losses and bad loans in the world’s second-largest economy, and could put more pressure on China’s stock markets, which have been pummelled [sic] to 14-month lows.

China’s stock market is a small, relative matter; the more troubling imbalances lie and remain elsewhere. This change in production profitability is concerning on three fronts; first in terms of where China’s economy, even in just industry, might actually be at right now. GDP says slowing but rather steady; these figures and many others suggest quite the opposite.

China saw annual industrial ¬profits fall for the first time in more than a decade, prompting calls for strong stimulus to boost growth, even as Premier Li Keqiang on Wednesday vowed to cut loans to zombie firms and ¬increase financial support for high-tech industries.

The gloomy figures add to the economy’s grim start to the year, coming amid growing panic over the depreciation of the yuan and state media reports on short sellers’ “attacks” in manipulating the market for the renminbi and other Asian currencies.

“For the first time in more than a decade” is becoming a consistent qualifier for these sorts of economic indications. A week ago, China reported electrical output and steel production now at just such historical comparison:

China’s output of electric power and steel fell for the first time in decades in 2015, while coal production dropped for a second year in row, illustrating how a slowing economy and shift to consumer-led growth is hurting industrial consumers.

China’s economy grew at its weakest pace in a quarter of a century in 2015 and efforts to restructure have not only slashed demand but also exposed massive overcapacity in industrial sectors such as coal, steel and power.

Despite these dire results and measurements, there is still this tug of “consumer-led transition” that, as noted in the quote above, remains as a bulwark optimistic sentiment. It can be distilled as if an economy operates in completely discrete and replaceable fashion; as if when industry struggles then services will just continue on that much better until industry no longer matters at all; and if industry really, really struggles, consumption and the service economy should only factor a minor nuisance being so separated. There are no such Chinese walls (pun intended) within an economic system (which extends globally).

That brings up the second contradiction noted by persistently decreasing industrial activity in China (and elsewhere). To this point, despite production and output cuts (and to capex and capacity growth) there has yet to be the major transition to across-the-board resource reduction, including and especially labor. In other words, consumption in China might not look as bad as production but only because there are time lags and frictions (as economists call them) that forestall synchronization even in these downward recessionary legs. Once production stalls and contracts long enough, especially in profitability terms, businesses will eventually seek to harmonize production with their resources – the very bad news of total cutbacks, including and especially pay and then labor in full.

China’s business confidence and recruitment activity slipped to record lows in January, a survey showed, adding to signs of weakness in the world’s second-largest economy that could prod policymakers to roll out more support measures…

The staffing index fell to 50.3 in January, near the 50 no-change mark, from 50.8 in December, hitting its lowest since the survey began, as businesses have become more hesitant to recruit as economic activity weakens, the survey showed.

And:

The slowdown in the Chinese economy has spread its tentacles to China’s white-collar workers who have received fewer year-end bonuses, according to a survey carried out by a recruitment company.

The study by Zhaopin, a Beijing-based recruitment website, said 66 per cent of the 10,615 white-collar workers polled had not received, or expected, a year-end bonus.

That compares with the 61.2 per cent who gave the same answer when polled the previous year.

About 14 per cent of the people surveyed did get a bonus for 2015.

The average paid out was over 10,000 yuan (HK$12,000), nearly 3,000 yuan down from 2014, the survey showed. Workers were polled in 32 cities across China.

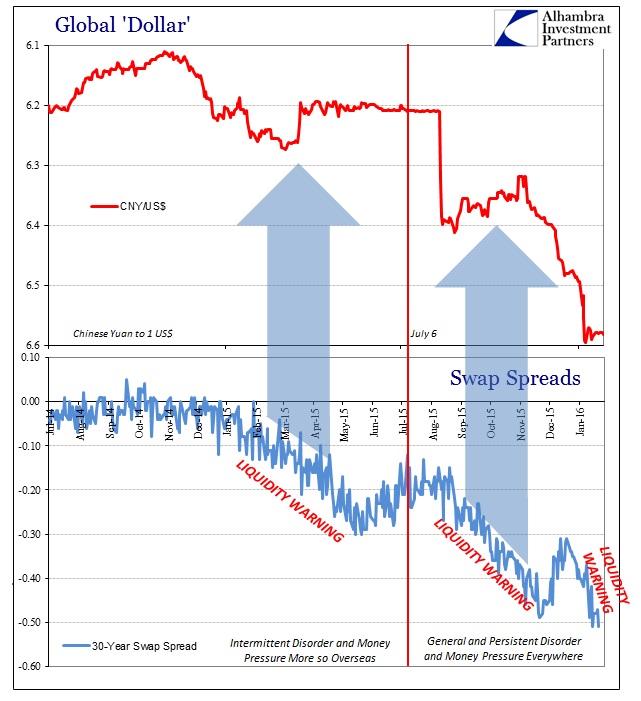

The production decay is only, perhaps, just now starting to impact the wider Chinese economy. It counts not just in resource management and eventual capitulation on those terms, but also financial terms – precisely the problem with China’s “outflows.” This is the third worrisome notice from China’s industrial profitability, namely that defaults or at least perceptions of default risk will only exacerbate an already tenuous position for China’s financial networks; especially its “dollar” short.

As the eurodollar standard built China in what looked like “hot money” inflows, that created lending formation and chained liabilities predicated on China being China forever; not China placing all its hopes and dreams on an unproven and hardly-detected consumer transition (that wasn’t really specified until economists started to belatedly recognize “something” was wrong with industry where they were sure nothing ever could be wrong). There are enormous financial implications in the slowdown as it reaches unknowable trigger points, some of which we have undoubtedly already witnessed. If you are a “dollar” provider into China’s banks, as NPL’s rise with this production massacre you are not going to remain statically attached while it all seems to get worse and worse (especially as central bankers and “experts” continue to protest there isn’t anything wrong in the first place that temporary tweaks won’t alleviate).

Economics becomes finance, and finance only furthers those negative economics. Financial distress in and of China both confirms the onrushing economic disaster as it was, while suggesting, because financial imbalance has not yet relented, not even close, much more to come.

Our three parts then sum to: China’s industry persists at only getting worse even though it has already reverted to a state not seen in a decade or more; consumer appearances may seem generally optimistic despite all that but only because industrial activity has yet to fully make adjustments through resources and labor; and financial trends are likely already at the stage of self-reinforcement within and without. You can see why China’s problems might trouble Citi’s economists and staff researchers in a way that perhaps the bank’s CEO might rather gloss over and around.

“Our” problem is that these trends and analytics are not just for and of China. There are no discrete pockets of fortified economic resolve with which to withstand a global “manufacturing recession.” There are only interconnections between individual economic circumstances that are augmented, amplified and affected by reflexivity in financial markets and conditions. That Citigroup is now recognizing this as a very real possibility, in sharp contrast to last January’s “transitory” commandment, shows how truly far along the economic and financial disease has infiltrated – globally. After all, China’s vast industrial might was built through eurodollars to service “global consumers”, of which Americans account for the bulk; upward as well as downward.