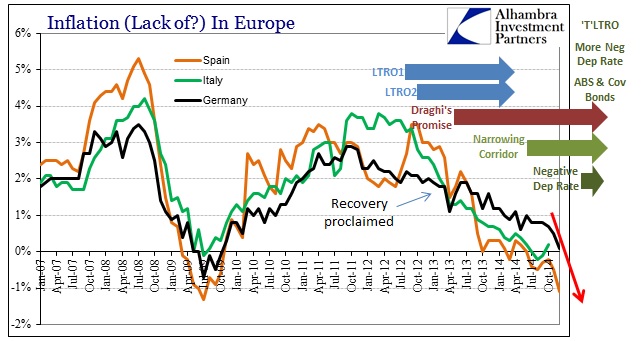

The “inflation” results out of Europe this morning highlight and emphasize the disingenuousness at the heart of monetary economics. While some of the “peripheral” nations (as if they are less European) are deeply into “negative inflation”, Germany (as if it is more European) has been an almost singular source of what the ECB views as a standard. However, even Germany is now on the verge of acting, “unexpectedly”, downright peripheral.

The annual rate of inflation in Germany, measured according to common European Union standards, was 0.1% in December, while prices rose 0.1% also on the month, the Federal Statistics Office said Monday. The yearly rise was the weakest since October 2009.

The figures were weaker than analysts had expected. Economists in a survey by The Wall Street Journal had projected the German consumer-price index would rise 0.3% both on the month and on the year. In November, prices rose 0.5% in annual terms.

With these results it is almost guaranteed that “inflation” for the combined whole of Europe will have been negative in December. And while that can be attributed to energy, but not energy alone, it simply begs the same problems as have been apparent going back to the 2011 euro crisis.

“Clearly there’s a high probability of negative inflation for the eurozone” in the wake of the German figures, said ING Bank economist Carsten Brzeski in Frankfurt. “It’s increasing pressure on the ECB to act.”

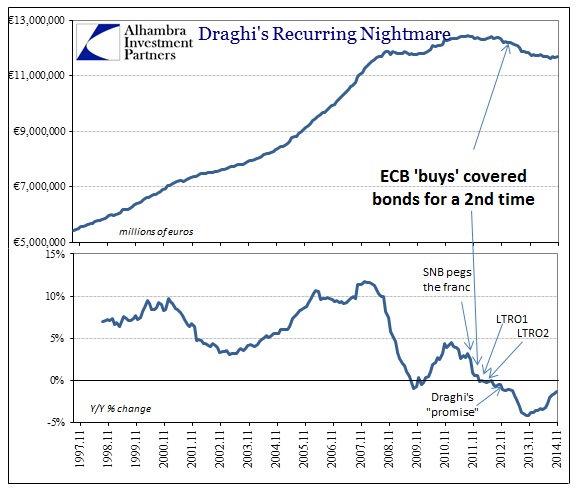

As per usual with what is left out by the obligatory credentialed economist, what hasn’t the ECB done yet? It’s not as if the central bank has been idle for the better part of three years, sitting aside and watching the economy sink further and further. In some respects, and contrary to the notion of these economists and their credentials, the ECB has gone further than the Fed in trying to engineer “something” out of nothing. Rather than “pressure on the ECB to act” it is instead the full mark of failure of all prior actions. The ECB in taking on these actions promised nothing short of full restoration in finance and economy, instead failing to deliver on even restoration as the economy lurches further toward a 2008-type abyss (what are oil prices saying, after all?).

The answer is, apparently, a European QE; to which the rest of Europe outside the policy class should respond with another parsed shrug. How much lower can nominal rates go in Europe? To the ECB, however, nominal means little as it is spreads that matter, which is exactly where they are so very powerless. Interest rates on the German bund curve may be negative out to 5-years, but what is the rate at which a Portuguese company will borrow?

That suggests both the problem and the solution, as it matters nothing what the interest rate might be when nobody will lend to the Portuguese firm at all. Central banks do nothing but push on the most visible parts of the financial spectrum with only the hope that it will cause a “portfolio effect” in banking; a European QE to purchase sovereign bonds regardless of cost or price “should” make banks look elsewhere for profit. Of course, European banks have already been buying sovereigns regardless of cost or price precisely because of ECB-driven profit, so there isn’t much to suggest any change suddenly toward favoring the shrunken business sector of the periphery (which now includes all of Europe, apparently).

Lending in Europe still shinks, including, which can only be a blow to all monetary expectations, interbank lending. Nothing the ECB has done has dislodged this continental predilection for the opposite of what the central bankers and economists all intend; as if this were 1930 or 1936 yet again. Failure is so widespread and significant that nobody seems to even notice the monetary fragments contained within it.

As with Japan, this raises the larger questions about orthodox monetarism not just in Europe or Japan but everywhere. It is downright absurd that lower oil prices in Europe will put more pressure on the ECB to counteract them while at the very same time lower oil prices in the US will be only “transitory” and uneventful for the FOMC. If oil prices are “transitory” in the US, why are they not in Europe? That is particularly curious as they are, in fact, the same oil prices everywhere.

And where is the consumer “boost” in Europe? Oil prices are an unmitigated disaster in Europe meaning that only more monetarism is “needed”, while in the US they are judged wholly and solely beneficial to the pocketbook. This lack of consistency might lead one to observe a curious relativism in economics that did not exist prior to 2008. In that sense, monetary economics is simply making it up as they go because, as I have said time and again, they have no idea what they are doing.