The mainstream view of the unemployment statistics suggest that any weakness in the US economy, manufacturing or beyond, will be temporary and shallow because employment growth remains robust. The question is not whether the statistics suggest such a trend but rather if those accounts correspond with anything real. As noted earlier this week, even the Federal Reserve’s relatively new measure of broader employment conditions has registered a clear deviation due to economic weakness that amplified toward the end of 2014.

At the very least, there is enormous pressure in the energy sector. It is being felt as a double shot from oil prices affecting direct business and now an almost certain turn in the credit cycle that will shut off additional liquidity just when weaker firms need it the most. The latest quarterly update from oil services giant Schlumberger is all that is necessary to understand the economic “headwind” coming from the energy space:

“The decline in global activity and the rate of activity disruption reached unprecedented levels as the industry displayed clear signs of operating in a full-scale cash crisis,” Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Paal Kibsgaard said in an earnings report Thursday. “This environment is expected to continue deteriorating over the coming quarter given the magnitude and erratic nature of the disruptions in activity.”

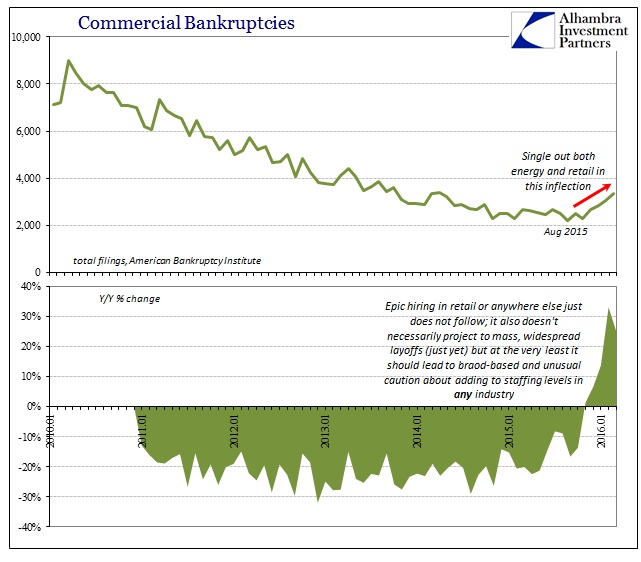

No cash and no prospects for achieving more junk flotations mean only more of the worst case – bankruptcies and, for the junk bubble, defaults. The significance of the oil industry is more than just its epic fall from flush and grace; it represents the first segment that has already passed through the economic boundary and there are already a number of other sectors ready to follow into the amplified downdraft. This morning I found that it is both oil and retail that is leading the current turn in bankruptcies already.

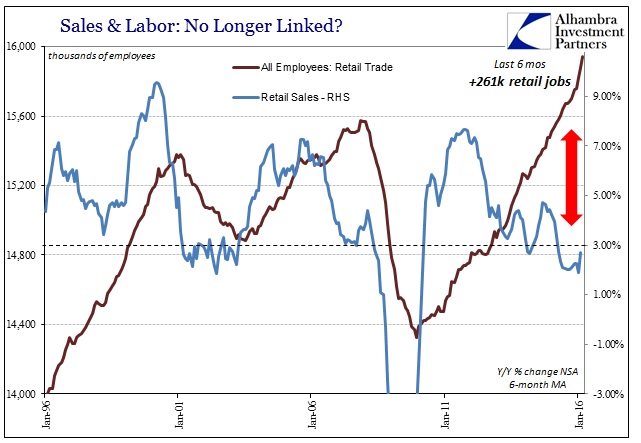

The jump in commercial bankruptcies and the timing of it corresponds quite well to what we find in actual consumer spending, especially activity in goods or just retail sales. It does not correlate at all with what the BLS is projecting about hiring and employment in the retail sector. Even if retail pressure is only just beginning, the last trend you would expect to find is sustained hiring at a truly historic rate. Since this downturn in activity is not just a sudden one or two month appearance, it is far more sensible to assume that retailers would have been cautious about staffing far a long time already.

Again, the inflection in commercial bankruptcies, especially retail firms, and the notable and sustained dropoff in retail sales makes sense; the BLS’s calculated strength in hiring in retail and the whole economy does not.

It also cuts against the idea that this is some temporary problem even though temporary (or transitory) now stretches toward a third year. Some of the current rush of renewed optimism in certain riskier markets has been due to the idea that January and February were the worst of it, and that by March better economic numbers were the start of a real and durable uptrend. That was, in my view, always false hope and a misreading of March’s estimates especially in comparison to the very relevant longer-term trend. In other words, that some accounts were better in March did not suggest anything other than perhaps overall conditions just weren’t quite as bad as at the start of the year. That’s a far different proposition as it really isn’t saying much positive at all; less atrocious is still atrocious.

That view appears consistent with continued credit problems and even now potential retrenchment in manufacturing. The Markit Manufacturing PMI for April (flash) dropped to barely 50 and the lowest level (for Markit) of this “cycle.”

US factories reported their worst month for just over six-and-a-half years in April, dashing hopes that first quarter weakness will prove temporary.

Survey measures of output and order book backlogs are down to their lowest since the height of the global financial crisis, prompting employers to cut back on their hiring.

Unlike the view from the unemployment rate, a broader range of less imputed data suggests that economic weakness overall may have past that point of being self-reinforcing; that what Schlumberger’s CEO describes of oil services and indeed the whole oil patch is the future for many more industries. We just don’t know how far into the future that growing possibility might be (slope and all that).

What should be painfully obvious by now is that the major employment numbers have made themselves irrelevant. The “best jobs market in decades” that began supposedly in 2014 had absolutely no bearing on the sudden and “unexpected” weakness of 2015; had it been real and not just some BLS phantoms of upward biased variation it would have. Instead, the very idea of “transitory” was based on nothing more than the Establishment Survey and the unemployment rate’s isolated prompt for “full employment.” Weakness, of course, only continued and in reality the economy is only now weaker still. It is far beyond the bounds of reason to expect that the economy, which was conspicuously feeble before, became even more so to the point of contraction in many vital areas, now turning the credit cycle and jumpstarting, unfortunately, the bankruptcy trend, and through it all US businesses continued to hire at a rate not seen since the halcyon dot-com days of the late 1990’s.

Again, the payroll reports are irrelevant. Actual economic analysis and fruitful interpretation lies only in ignoring them. Viewing the economy only through the lens of the BLS figures leads to a world that just doesn’t exist; it’s why policymakers, economists, and the media can’t seem to gather that the recovery ended years ago. Recognizing that situation pulls the economy of 2016 as it is back within the boundaries of reason, leaving “unexpected” out of all of it.