There can be little doubt now outside of orthodox economics that the global economy is actually slowing, not accelerating as has been predicted. Economists themselves, however, continue to claim that things are getting better when the data strongly suggests otherwise. The latest depressing figures are from a pair of (orthodox) supranational organizations. First, the World Trade Organization (WTO) drastically reduced its estimates for trade growth this year, cutting them sharply from just a few months ago.

The World Trade Organization cut its forecast for global trade growth this year by more than a third on Tuesday, reflecting a slowdown in China and falling levels of imports into the United States.

The new figure of 1.7 percent, down from the WTO’s previous estimate of 2.8 percent in April, marked the first time in 15 years that international commerce was expected to lag the growth of the world economy, the trade body said.

While it will come as a shock to Janet Yellen’s public face, the WTO specifically cited both of the world’s biggest two economies and not just China as the unrelated “overseas” (from the US perspective) problem. For all the reliance upon the unemployment rate here, there is a shocking disconnect in how supposedly rapid and sustained job growth just hasn’t translated into economic gains accrued anywhere. For an economy at “full employment”, there just isn’t any “demand” growth, a fact being felt and described in grim detail especially overseas.

The general director of the WTO, Roberto Azevêdo, shifted into politics by decrying so-called protectionist policies and the rising tide of populism increasingly hostile to what economists still identify as “free trade.” Importantly, however, Azevêdo fails to explain why this version of “free trade” is a benefit and how disdain for it is closely linked to not just the current slowdown in trade and overall growth by why there is a global slowdown (that is clearly getting worse) in the first place. Why would people trust economists pledging benefits of “free trade” when there aren’t any apparent economic benefits period?

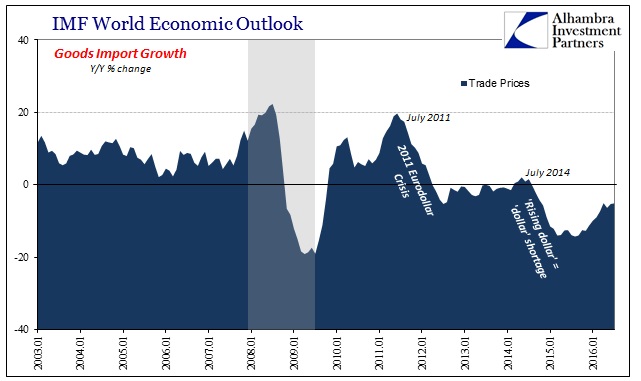

The other organizational warning was issued by the IMF, also related to international trade. The Fund noted commodity prices as a singular point of contention (also not explaining them) while further referencing how inflation expectations are supposedly still well-anchored in the medium and long terms. Unlike the FOMC, however, the IMF did not use the word “transitory” to describe this problem because it just doesn’t apply, a fact very well established in the IMF’s data on trade and prices.

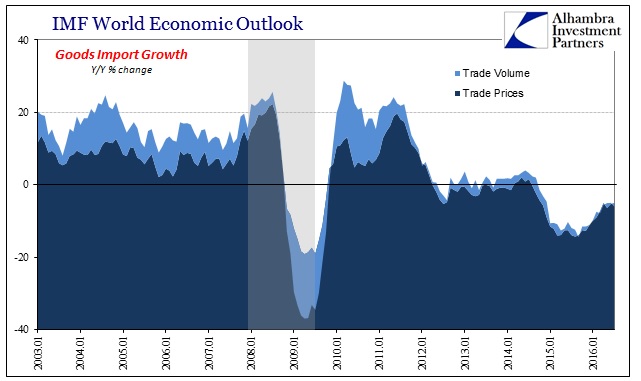

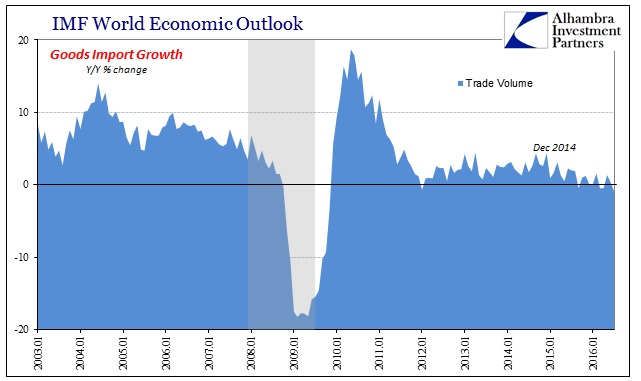

While also warning about “protectionism”, the IMF estimates for trade in goods continue to be brutal. And it is the same worst case that we see in nearly all economic accounts, proving to be much worse than any single recession – even the Great Recession. Global total imports of goods fell sharply starting in late 2008, but the entire contraction lasted just 12 months. The depth was shocking, in total about 33% year-over-year at its worst, with commodity prices then accounting for about half the decline.

In the aftermath of it, trade growth has been a huge problem for years now, where the dropoff in early 2015 was just the latest amplification of that problem. In fact, that was the theme of the IMF WEO chapter, trying to get some idea of the 2012-15 problem as if it these economists suddenly see it for what it is. Despite claiming year after year that recovery was just about to appear, the IMF is now finally confessing that in all likelihood it never will. It isn’t recession, it is far worse. From the IMF:

Eventually, persistent disinflation can lead to costly deflationary cycles — as we have seen in Japan – where weak demand and deflation reinforce each other, and end up increasing debt burdens and hindering economic activity and job creation.

These are orthodox buzzwords communicating an economic depression without admitting to it. Even the IMF is worried that the whole global economy is on the road to Japanification. But by being ever-faithful to that orthodoxy they all but guarantee it. Mainstream economists refuse to see all this for what it truly is because for them the ideology comes first.

Even in these trade statistics, the answers are right in front of them. The supposed mystery about all of this is superimposed by unyielding faith in their dogma. If you take the trade estimates in its two pieces, you see very clearly what is transpiring globally.

Prices lead and volumes follow. In 2008 and 2009, they were together in close proximity because that specific event conformed to the traditional mechanics of a sharp, condensed recession. In its aftermath, however, prices are the catalyst. As prices fall especially during this “rising dollar” volumes have reacted not as recession but as perpetually slow (and now shallowly shrinking).

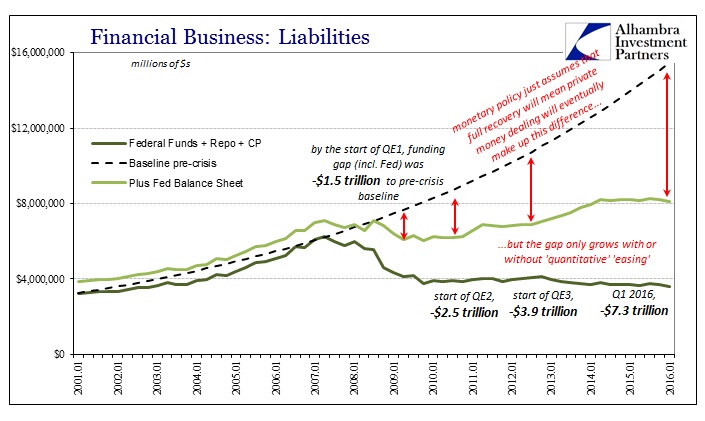

It is this slow death that allowed economists including those at the IMF to claim for years that the recovery was on its way due in very large part to so much “accommodative” monetary policies. Now, seeing clearly in the further worldwide deceleration of 2016, central banks are to be treated as the victims of not enough “structural reforms” and rising “protectionism.” Changing this one variable unlocks all the answers; recognizing that there is no money in monetary policy harmonizes what we see all over the world. Monetary policy failed on all its promises not because it wasn’t consolidated by fiscal efforts, rather it was a disaster because it never solved (really never even addressed) actual monetary contraction.

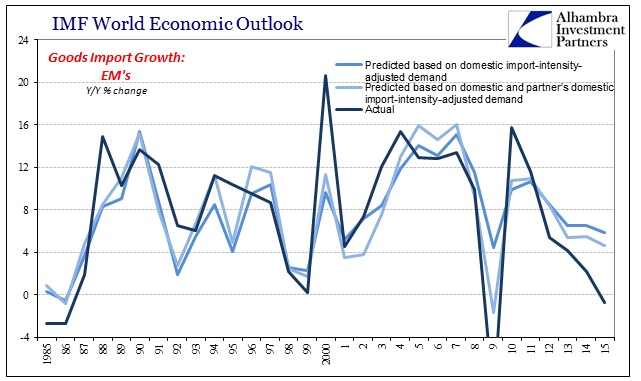

That is the only way to link the global economy in such synchronized fashion. It was so clearly the case in the Great Recession (which is increasingly described in outlook even by these orthodox outfits as something other than a recession) where the whole global economy fell off especially after the panic. Even in trade terms among the IMF data we can observe this monetary phenomenon by how it has affected emerging market economies the most. EM’s are far more vulnerable to monetary conditions and thus the bulk of the slowdown in global trade (and global economy) is being pulled from the EM’s including and especially China.

The IMF through its various forecast methods only anticipated EM trade growth decelerating to near its longer-term average after 2011. Instead, EM trade actually contracted in 2015 and appears no better in 2016. Those are among the worst results in the series, already last year below even the Asian flu episode.

It is unchallenged assertions that drive all these ambiguities supposedly abounding across the world. The biggest one, that which has been most disastrous, is the idea that the each central bank has control over the money supply by viewing “bank reserves” as the appropriate monetary base. By just two false assumptions these economists are years behind the times; the first is that money contraction is impossible because of positive actions, often immense, with and for each distinct monetary base; second, that money is a fragmented concept left to each individual circumstance. In other words, there is no single world money or economy to the IMF or WTO, only individual closed systems whereby the monetary authorities in each acted much more than appropriately.

From these demonstrable falsehoods are derived all the confusion, starting with the expectations for recovery in the first place. Fragmentation is very real and the true problem, just nothing like what economists believe. The global “dollar” system no longer functions as a fluid whole (and there are serious questions as to whether it ever did, meaning that rapid growth in “dollar” volume obscured or truly “papered over” its inherent flaws that are now far more obvious without exponential expansion), which has the effect of depriving the global “dollar short” with sufficient vigor to be carried out into the real economy in likewise fluid and sustained fashion. A monetary system constantly prone to interruption and immense difficulty is truly an economic problem; therefore, where money is most important to economic growth (goods and trade overall but especially as EM goods and trade) we should expect to find a lack of both.

“Protectionism” isn’t the “right” response, but it is at least rational given these conditions because those in favor of it (as a general idea) far better understand what is taking place. Most people knew there was no recovery long before now, meaning most economists are just starting to catch up to the laypeople they abhor. As I wrote some weeks ago specifically about this diverging view on trade:

This statement can be taken two ways: that economists have some explaining to do, or economists shouldn’t bother explaining themselves. Mankiw chooses the latter…

The difference between 1992 and 2016 is that we are no longer forced to listen to the Mankiw’s of the world exclusively. The opening of the internet means that people can get useful information from someone who never set foot inside Harvard, MIT, or Princeton, where credentials matter much less if not at all; and that upsets them on a personal level as economists’ own failures come back to haunt them as they increasingly lose their grasp on the population at large. Economists own this depression and the populace is finally starting to realize it as an empirical, established fact of evidence entered outside the legacy media in rejection of “free trade” theories.

By view of both the IMF and WTO updates, economists do have a lot of explaining to do; and they still are choosing not to. So long as that is the case, this global “mystery” of clear depression will remain and, as the latest estimates further show, continue to get worse.