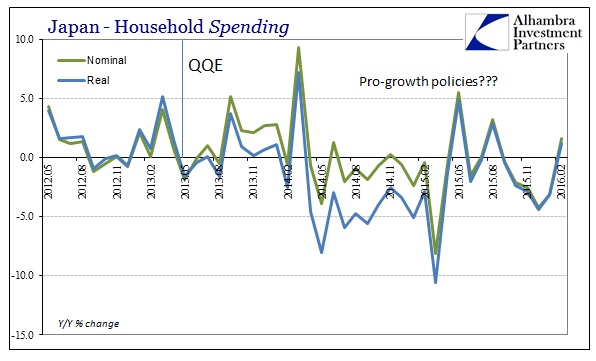

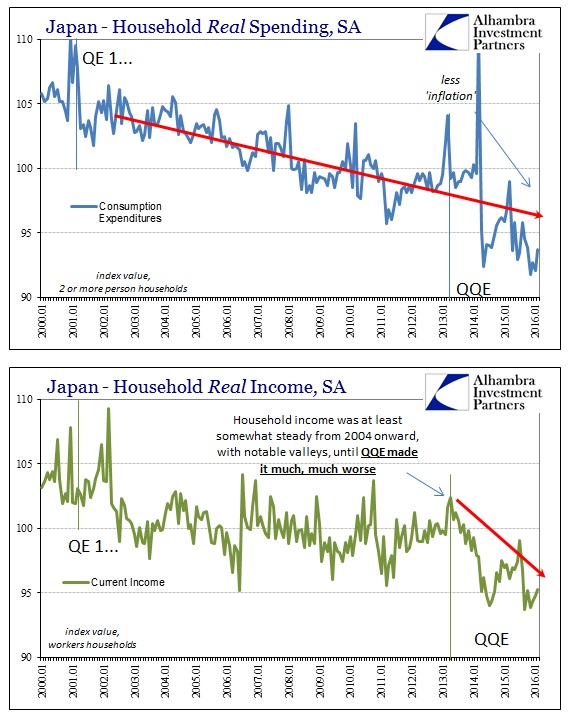

Household spending in February 2016 in Japan rose year-over-year for the first time in six months. That was the sum total of any good economic news for the monetary-stricken economy, and it doesn’t really survive closer inspection. The rise in spending was due largely to “other” activities you don’t associate with strong economic rebounds. The overall figure was just +1.6% in nominal terms and +1.2% in real terms, but that was due largely to a 6% jump in spending on food, +13.8% in spending on medical care, and +20% on education (all nominal changes).

Those gains were balanced by the usual digression in household circumstances, including a 10% drop in spending on fuel, light and water, -4.3% in furniture and utensils, and -4.0% on clothing and footwear. This breakdown across spending categories explains the big difference in the broader category of household spending against the more economically-sensitive retail sales estimates that fell 2.3% month-over-month (seasonally adjusted).

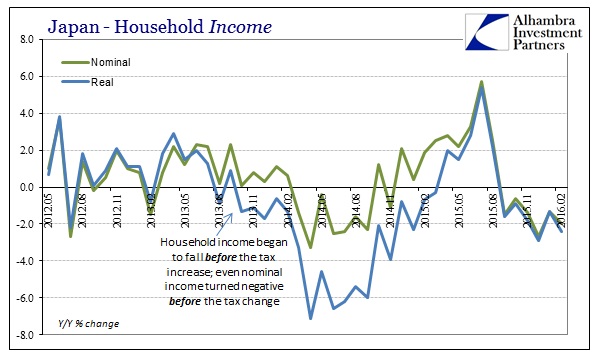

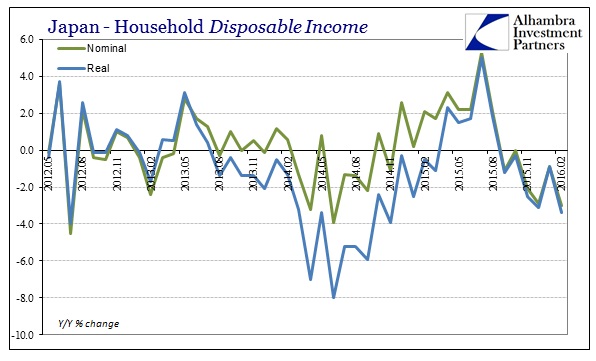

Household income declined yet again in February, down 2% in nominal terms and 2.4% adjusted for the CPI. Disposable household income, factoring taxes, was even worse at -3% nominal and -3.4% “real.” The income numbers suggest retail sales are probably closer to the actual economic baseline for Japanese consumers.

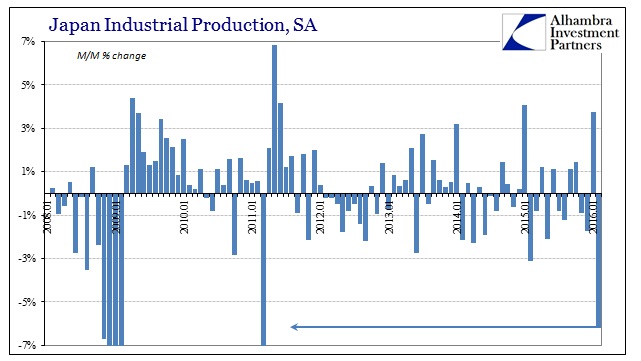

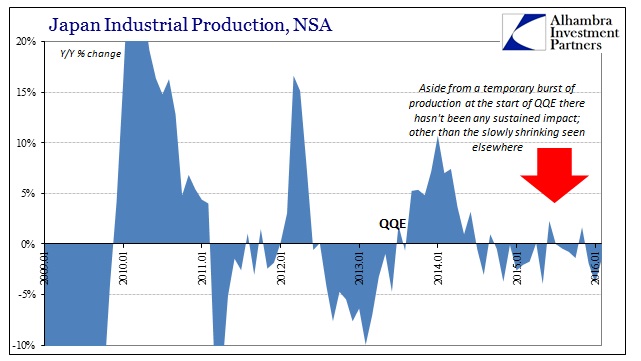

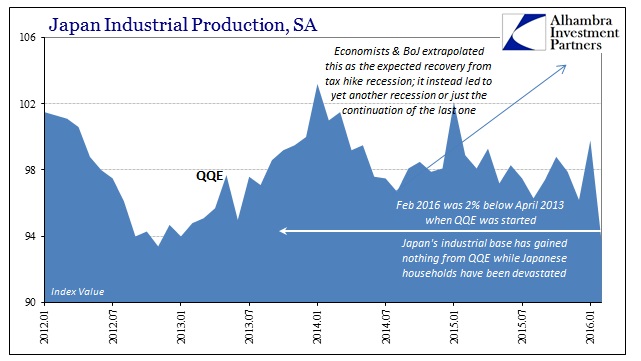

Unfortunately, Japanese industry has now taken to the plunge as well. Japanese industrial production declined an enormous 6.1% (M/M) in February from the usual positive January. That was the largest monthly contraction since the 2011 earthquake/tsunami, except that the only disruption this time is decidedly unnatural. In unadjusted, year-over-year terms, IP has declined in six of the past seven months and has been positive in only four of the last twenty.

Some of the decline in February can be attributed to steel disruption at one plant that halted Toyota’s production runs for a time, but that was at the margins of both weak internal “demand” as well as the ongoing plunge in exports (echoing China’s view of global, including US, “demand”).

The ministry estimates that production for the three months ending Thursday may shrink. This casts a shadow over gross domestic product for the whole quarter, underscoring Japan’s struggle to bounce back from a contraction at the end of last year. Shipments of capital goods also slumped last month, indicating sluggish business investment.

“The slump in industrial output in February suggests that manufacturing activity will contract this quarter,” Marcel Thieliant, senior Japan economist at Capital Economics, wrote in a note. This means there is a growing risk that the economy won’t expand this quarter after the contraction in the final three months of last year, Thieliant wrote.

Even taking out the fall in production at Toyota and the lunar new year, production for February was poor, according to Hiroaki Muto, chief economist at Tokai Tokyo Research Center.

“The outlook for production looks weak as demand in emerging nations, as well as industrialized nations including the U.S., is slowing,” Muto said. “Japan’s economy may avoid falling into a recession, but any rebound in the first quarter will be weak.”

This is much more than arguing about technical recession or whether one quarter might show a positive sign in GDP after being up and down for years now. The argument in favor of the negative redistribution scheme under QQE (or any QE anywhere) was that rising “inflation” would certainly hurt Japanese households but only at first. As the rest of Japan Inc. resurrected and benefitted, the pain of being on the wrong end would be completely overwhelmed and alleviated by full recovery and sustainable, broad-based growth thereafter. We know households have taken the burden, as every piece of data shown above absolutely declares.

What are missing are benefits to all this; any benefit at all. It was all an illusion; a con. Japanese businesses gained more profit in nominal yen terms but they aren’t actually doing anything more to receive it. They are doing less, actually, as the total number of hours worked slowly shrinks, and incomes with it. In terms of industrial production, the index value (seasonally adjusted) for February 2016 was a little more than 2% below what was figured for April 2013 when QQE started. For all the admitted negatives aimed at the household sector, redistribution hasn’t found anything to offset it. The opposite has actually occurred as now Japanese industry is also doing less for the three years of “extraordinary” monetary “stimulus.”

Just as in the US and elsewhere, economists and policymakers in Japan were easily convinced in the second half of 2014 by a temporary increase in industrial production and other accounts as if that proved the tax hike was to blame for the 2014 troubles and that the struggles therein would be limited to that circumstance. That bled into suggestions of 2015 where Japan, as elsewhere, was supposed to find only a “transitory” deviation from what would surely be QQE’s fruitful completion. That was a fundamental misreading of the situation in not just Japan but everywhere else – positive numbers do not make a real recovery. It is more difficult to see and muddied in other places (especially the US and its bond market), but Japan was never going to take off with that huge and continuous drag on household fortunes. It’s the same everywhere else monetarism is applied.

In fact, no matter how many QE’s and other activities the Bank of Japan has undertaken since the Great Recession, industrial production remains 20% below the start of that year. That is not a misprint; Japan IP is still 20% smaller in the first months of 2016 than the first months of 2008 as if the whole economy just shrunk never to return (at least so long as “stimulus”). Only the financial and corporate sectors very narrowly count any of the QE’s as being “stimulus”; the rest of the country has been only impoverished.

After the NIRP fiasco, there haven’t been as many calls in the mainstream for more Bank of Japan action (though there will always be some). Instead, the tide is slowly shifting back to the fiscal side just as I suggested in late 2014.

I suppose if the distance between these bouts of actual awareness is long enough, we could sadly be in for interchangeable failures of different pieces of statist intervention. We started with Keynesian government “stimulus” that relented to purely monetary “stimulus” and now seem to be heading back toward government spending once more. Once that inevitably fails, “they” will probably resurrect “Friedman” to replace “Keynes”, this time with the “right amount” of monetarism (rereading Chapter 11 in A Monetary History probably). And so it will go back and forth with nary a reference to the actual economy until the entire globe is encompassed in fullblown Japanification for a quarter century or more.

Amid a politically eventful year, calls are growing within the government and ruling parties to compile stimulus steps to gird the flagging economy ahead of a key summit and the Upper House election.

Though doing so would go against the nation’s efforts to heal itself fiscally, a pledge by Group of 20 economies to “use fiscal policy flexibly” is likely to be cited in support of stimulus at a time when global growth is weighed down by recent market turmoil…

As Japan holds the rotating presidency of the G-7 this year, it “would like to contribute to the sustainable and robust growth of the world economy,” the prime minister said Tuesday, heightening the view that the government is eyeing fiscal spending to shore up the world’s third-largest economy.

Once that inevitably fails, and after a long enough period of continued ineffectiveness, the Bank of Japan will probably be tasked to once again move to the forefront and proclaim necessity to do something – as if all the continued QE’s of today, by then far in the past, never happened. There is one commonality to the mainstream consciousness of “stimulus” both fiscal and monetary; it has no memory. That is why the solution to all this global mess will not be decided by some DSGE model update or inside the current halls of whatever Treasury Department or Finance ministry. The answer is purely political at (hopefully) the voting booth that does contain the historical record of everything that didn’t work and was, in the end, very harmful and impoverishing; and that was everything.