Central banks have pushed money market rates to nearly zero in every DM financial center—and the ECB is now even loudly toying with the prospect of negative deposit rates. Yet mindless as this is on its face, the world’s monetary central planners plow forward unblinkingly as a matter of doctrine. According to the latter, zero money market rates will induce households and businesses to borrow and spend, thereby triggering a virtuous cycle of growing output, jobs, incomes and even more spending.

As a practical matter, therefore, the world’s major central banks have embraced the old 1960s fiscal Keynesianism in the guise of monetary “accommodation” designed to generate more spending, jobs, growth and inflation. What is different, of course, is that this new Keynesian dispensation can be implemented by a tiny cabal of unelected bureaucrats operating mainly in secret out of the control rooms of central banks where there is no messy budget politics to deal with—to say nothing of votes by the peoples elected representatives. And it can be reduced to a one-decision mechanism for injecting the Keynesian elixir of artificial, credit-fueled spending into the macro-economy—-namely, “lower for longer” on the money market rate.

To be sure, the four largest economic areas of the world—the US, EU, Japan and China—- give every sign of being saturated with debt and tapped out at “peak debt” ratios relative to their halting rates of income growth. Indeed, combined public and private debt in these economies now amounts to nearly $180 trillion or 4.5X the level which obtained during the mid-1990s before monetary central planning was embraced on a worldwide basis.

So it might be wondered why in principle the central banks are so determined to elicit even more borrowing and even higher leverage ratios. That is especially true given the overwhelming evidence that households and businesses, in fact, are not increasing their leverage ratios in order to spend more on goods and services than they can afford out of current income and cash flow.

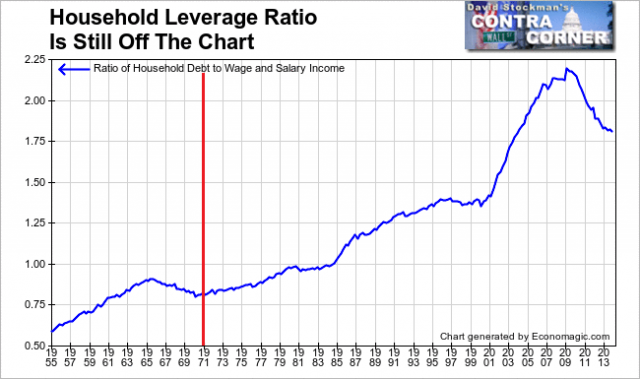

In the case of US households, for example, the ratchet effect from monetary easing over the last 40 years is no longer working as the graph below powerfully demonstrates. “Peak Debt” ratios were achieved at the time of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and has been declining ever since.

Likewise, bank debt owed by business in the Euro Zone area has now declined by 10% from prior peaks and shows no signs of reversing. The fact is businesses throughout the EC are still massively over-leveraged and the demand for loans among remaining credit worthy borrowers is tepid at best.

Even in the US—where non-financial business debt has grown from $11 trillion to $13.6 trillion since the pre-crisis peak—virtually all of the gain has gone into financial engineering. That is, the added leverage has been used to inflate the price of existing corporate equities and other securities by means of massive stock buybacks, special dividends, LBOs and debt funded M&A deals. By contrast, real spending on plant and equipment—-i.e. the so-called “aggregate demand” sought by Keynesian policy—is still nearly $70 billion or 5% below its late 2007 peak.

So what we have is a regime of monetary plumbers who keep banging the money market rates to rock bottom zero—thereby utterly ignoring what the money market rate really is in a massively financialized, debt ridding system. In fact, it is the price of hot money—the single most important price in all of capitalism.

Stated differently, the money market rate prices the overnight rental cost of chips in the Wall Street gambling casinos and thereby regulates the flow of funding into the carry trades. At the end of the day, all of the Wall Street fast money trades are carry trades—whether they are funded through options, structured notes or outright repo and unsecured debt.

The lower, the longer and the louder the central bankers profess to embrace the regime of ZIRP— the larger, more diversified, more arcane and more globally extensive these carry trades become. And the more dangerous, unstable and opaque they become, too, because ZIRP destroys the natural short interest in financial markets. So doing, it massively subsidizes speculators who can buy dirt cheap downside insurance on the broad market while chasing the momo flavor of the day or week in what have essentially become one-way markets.

Indeed, the carry trades are the most potent form of speculation ever invented. After years and decades of central bank coddling, market rigging and bailouts if necessary, the global financial system is crawling with carry traders who constantly forage for new rips and runs. As a consequence, global financial markets are booby-trapped with speculative positions and maneuvers that concentrate enormous coils of risk and greed; and which also move and morph so quickly that they would be invisible to the monetary central planners, even if they were looking for them.

At bottom, ZIRP has turned the financial markets into dangerous, unstable gambling casinos where the protean forces of unhinged, one-sided speculation run rampant. Accordingly, their true function as an arena for price discovery and capital allocation have been completely impaired.

The following cogent analysis by GavKal of the inexplicable rebound in recent weeks of the “fragile five” EM currencies and financial markets—Brazil, India, South Africa, Indonesia and Turkey—provides a good case in point. In an environment where the US and European export market languish at sub-2% and sub-1% growth, respectively, and where China continues to falter, there is no economic reason for this sudden sharp rebound. All of the massive imbalances embedded in these EM economies, including unsustainable internal construction and investment booms, heavy dependence on yield-seeking international capital flows, large current account imbalances and corruption-riven internal governance, have not been alleviated in the slightest.

So the rebound has nothing to do with new facts or an upturn in the global and local economic fundamentals. Its just another lightening outbreak of carry trade speculation where short-term momentum has become the new flavor of the week. Needless to say, these momentum raids can and will reverse almost as quickly as the appeared.

Meanwhile, the monetary central planners continue to bang on the money market interest rate—oblivious to the fact that they are building-up a third and even greater financial bubble than the two which went before.

from Evergreeen GaveKal

Emerging Markets Carry Trade Looks Vulnerable

Over the last two months, emerging markets have delivered a handsome rally, with the MSCI emerging markets index recording a 7% return in US dollar terms, compared with just 1% for the developed markets. The trouble is that this rally has been driven primarily by investors’ growing enthusiasm for carry trades in an environment of declining global volatility. Experience teaches this is an engine which can all too suddenly be thrown into reverse.

The defining feature of the current run-up in emerging markets is that the greater the sell-off a country suffered last year, the stronger the rally it has enjoyed this year. As a result, the so-called “fragile five”—Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey, and South Africa— the markets most reliant on foreign capital and so most vulnerable during last year’s taper tantrum, are no longer looking quite so fragile. Since their lows in January, the Turkish lira has surged 13%, the Brazilian real 10%, the South African rand 8% and the Indonesian rupiah and Indian rupee 6% each.

It hasn’t taken long for the rebound to flow through to stock markets. In local currency terms, an investor with an equally-weighted allocation to each of the fragile five’s equity markets will already have seen his portfolio regain its previous high reached in May 2013.

As investors, we like equity rallies to be propelled by fundamental factors, like earnings re-ratings or growth surprises. But there is little behind this rally to suggest any sustainable economic healing. Sure, there are pockets of earnings re-ratings because of last year’s currency depreciation, but we see little in terms of broad-based economic surprises. According to the Citi Eco Surprise Index, economic data in the emerging market has largely surprised on the downside so far this year. Most forward-looking indicators, especially in Asia, are signaling no prospect of any decisive upturn in the growth outlook. What’s more, the prevailing direction of economic and monetary policies is hardly investor-friendly. Credit moderation remains the order of the day in China, while policy settings have been on hold among many of the other major emerging markets in the run-up to national elections. And with food prices turning up, monetary easing is now off the table for emerging market central bankers.

That leaves the search for carry as the principal engine of the current rally. The markets which sold off most violently last year, and which have rebounded most strongly over the last couple of months, are those offering the most attractive yields. As volatility in global financial markets fell this year, and lingering fears of emerging market (EM) contagion evaporated, the lack of yield on cash prompted investors to turn once again to the high yielding emerging market currencies and fixed income markets which took such a beating last year.

The widespread return of calm which has underpinned the revival of the EM carry trade is marked, and even ominous. Unless you are trading the renminbi or the Russian market, volatility levels in major equity markets, currency pairs, Credit Default Swap (CDS) spreads and basis swaps are once again approaching, if not already below, the lows seen last April. Even Chinese CDSs are at year-to-date lows, despite the worries over China’s growth trajectory, while volatility in the Brent crude market has fallen even as geopolitical uncertainty has mounted. While low volatility is nothing new in the era of financial repression, it still signals a remarkable rebound in confidence given expectations that the Fed will halt its balance sheet expansion within a few months.

On this premise, the moment that volatility returns, the EMs will be extremely vulnerable to investor repositioning. Quite what the trigger might be is impossible to say. But history teaches us that volatility rarely stays this low for long.

* * *

History, also teaches us the central planning on such a grand, global scale always ends in tears too, but for now the music is playing and the dancing, on “other people’s tab” must go on.