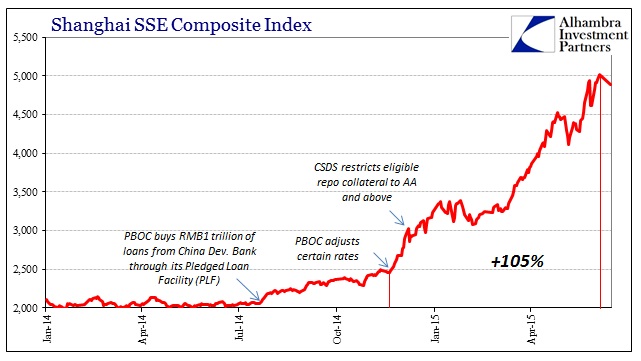

There can be no mistaking that Chinese stocks are in a bubble. Since November 21, the Shanghai SSE Composite index has risen more than 100%. Going back to July 22, the gain is nearly 145%. Those dates are not random coincidence, as they mark specific points of PBOC activity. The stock bubble in China is certainly a monetary affair, but in ways that aren’t necessarily comparable to our own stock bubble experience (twice).

There is, of course, great similarities starting with leverage; in China at the moment there is no shortage, which is precisely the problem. It is quite precarious, though, in that the PBOC has at times shown far more open contempt for Chinese stock margin than the Federal Reserve or Bank of Japan ever did.

Stock forecasters in search of an early-warning system for the next Chinese bear market are zeroing in on the country’s record $358 billion pile of margin debt.

When that three-year build-up of leveraged positions starts to unwind, regulators will struggle to limit the selloff, according to Bocom International Holdings Co. and Rabobank International. Almost all of this year’s biggest declines in the Shanghai Composite Index, including a 6.5 percent slump on May 28, were sparked by investor concerns over margin-trading restrictions. The securities regulator announced plans Friday to limit the amount brokerages can lend for stock trading.

Unlike central banks here and elsewhere, the PBOC has a vastly different understanding and appreciation for asset bubbles, at least to the point that in 2014 and 2015 under reform it is not shirking responsibility for them. The Federal Reserve, in particular, had long been against any linkage between monetarism and asset bubbles, believing instead that they were fully contained under “market” irregularities (that has evolved, somewhat, under the relatively new Yellen Doctrine). I’m not sure the PBOC ever went so far as to completely delink its own activities from asset bubbles, but it at one point was clearly embracing of them even if reluctantly part of a greater government mandate.

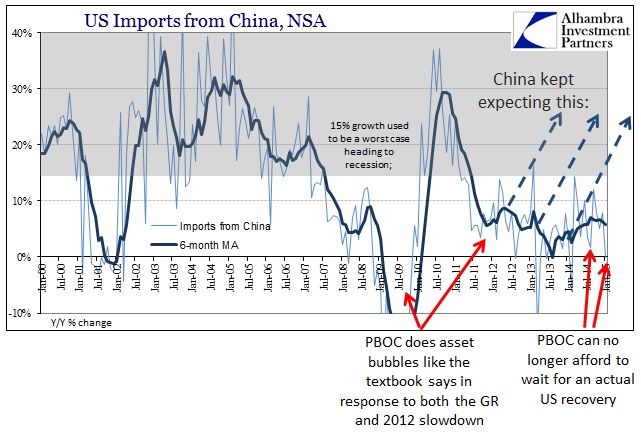

In trying to dig China out of the Great Recession mess, which is and remains a global affair, the PBOC did what all other central banks did, perhaps to an even greater degree. The distaste for the effort did not, at that time, undermine the scope, which simply became immense once the global economy failed to reach its first “benchmark” expectations. All central banks were expecting only to have to fill some time between the Great Recession and a robust recovery, but by 2012 certainly it became clear that the task was much broader and deeply embedded. Most central banks acted again, including the PBOC, but were again rebuffed by a lack of recovery; and indeed worse, an actual and sustained global slowdown from even the tepid pace of expansion from the trough.

By that time, the Chinese bubbles were immense and located mostly in various credit pockets – expressed through real estate and overdevelopment of many industries (oversupply). The stock market didn’t much figure. The reform agenda, born in late 2013, prioritizes managing the greater financial imbalances even above economic expansion, reversing the 2009-12 paradigm, placing the Chinese experience in the past few years very much in reverse of almost everywhere else in monetarism (which is why the PBOC right now so confuses economists and commentary).

To gain some ability in managing the credit bubbles, which had grown through Wealth Management Products but also Local Government Financing Vehicles, the PBOC in early 2014 experimented with a few limited credit defaults. The results right away were not encouraging, which seems to have forced the PBOC to alter its intended reform path. Seeing the negative reaction in liquidity, especially “dollars”, new efforts were implemented to simultaneously tighten and loosen – tighten the wasteful speculations that were inducing credit bubbles, while targeting liquidity for parts of the financial system deemed vital to the real economy.

Among the latter was the China Development Bank, which received on July 22 RMB1 trillion in funding support through the new Pledged Lending Facility (PLF). Some have likened this to a Chinese QE, but in reality it is far more of redirecting liquidity than any kind of broad and more familiar expansion. The rise in Shanghai stocks, however, began precipitously with that event.

While that might suggest stock “investors” reacting to “stimulus” as any others have around the world, in the context of reform I think it amounts to what always happens when you start to squeeze a bubble – it breaks out in other places. In other words, as it became clear what reform aimed to accomplish, mostly getting a handle on the credit creation and debt-driven expressions, some financial agents saw the writing on the wall and moved to the “next” open door, stocks, in a very conscious effort to get out of credit while still positively positioned.

That alternate view was aided on November 21 when the PBOC again made a targeted adjustment to deposit rates, and then further on December 8 when China Securities Deposit and Clearing Corp (CSDC) restricted repo collateral, largely of corporate bonds and notes, to AA or above. That cut repo eligibility in half, signaling that credit, especially low-rated junk, was no longer an open bubble door.

“The regulation will damp investor demand for lower-rated corporate bonds,” said Yang Feng, a Beijing-based bond analyst at Citic Securities Co., the nation’s biggest brokerage. “That may result in higher borrowing costs for LGFVs.”

Borrowing costs rose, but “investors” did not disappear – they simply traded junk debt for Chinese stocks. Banks have followed, somewhat, that trend by being rather eager to supply margin, a slighter swap than it might at first appear.

Analysts say the regulators’ exclusion of lower grade bonds from being used in bond repurchase contracts, a key source of secondary liquidity in trade, increases the risk of trading such bonds, depressing demand and putting upward pressure on yields…

“This is bound to have a major impact on the bond market,” said a dealer at a Chinese commercial bank in Shanghai.

“The Shanghai Stock Exchange’s bond market will be hit the most as China’s corporate bonds are concentrated in the stock exchanges, although the move is likely to spill over to the main interbank bond market as well to a lesser extent,” he said.

With traders already aligned to the Shanghai exchange, shifting from bonds to stocks as the PBOC cracks down was not a large leap. The banks were there, too, having been the great supplier of repo funds for traded debt issues; now piling up $358 billion in margin debt in short order instead of repo assets (the chart accompanying the article quoted at the outset shows the close relationship, as you would expect, between margin debt and the stock index price, receiving a major boost in late November 2014 after the first great ascension in late July; margin in Shanghai stocks has more than quadrupled since the PLF was first employed).

If the PBOC was committed to a broad-based monetaristic regime consistent with 2009 views, I seriously doubt stocks would have started to rise as they did since a widespread liquidity program would simply have fed back into the same credit mess as twice before. The very open and public change in monetary policy character is responsible for the change in asset bubble focus, especially as another round of defaults was “allowed” to occur late in 2014.

There is nothing in the latest re-adjustment that will impact especially the beleaguered housing sector, nor its backing in the Wealth Management Products. Instead, it seems to me the PBOC was intentionally careful to not give the “bubbles” much of anything, relying and focusing solely on actual businesses (and smaller versions at that) rather than the broad-based elements that marked all prior (futile) attempts at “stimulus.” That is the message that should have been received, that in other words this was a far different approach of the PBOC toward a slowing economy.

What the stock bubble shows is the unthinkable degree of difficulty in trying to actually manage letting air out of any bubble in an orderly fashion; they target for decline credit-funded junk WMP’s and it breaks out in stocks instead. It may already be too late, as growth declines still further month by month, but stock prices go even more insane, drawing in more and more “retail” accounts and regular Chinese. In other words, the reform idea may have been impossible from the start; that the PBOC went ahead anyway, and still continues despite all that has happened, more than suggests that they now recognize the most dangerous existence is asset bubbles, far and away more important than even “necessary” growth.