If there is any wonder why PMI’s deserve scorn, this morning’s twin bill delivered solid reasoning. Both the ISM Manufacturing Index and the Markit Manufacturing PMI declined, and both remained above 50. However, there was no real consensus about what any of it meant. Depending on the media outlet determining commentary about either, there was both positive and negative spin on each. Further, the internals of each survey showed quite divergent views in important subcomponents.

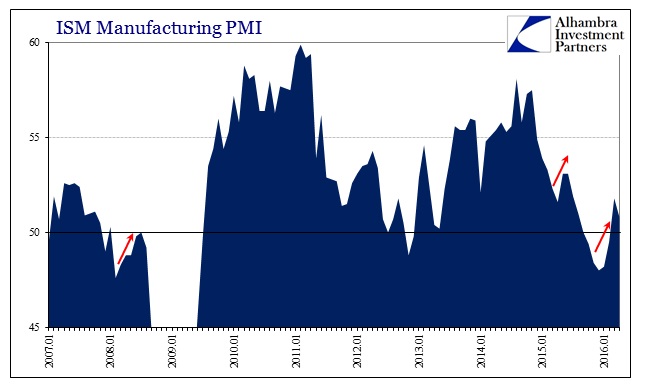

Starting with the ISM, the overall index fell back to just 50.8 after jumping to 51.8 in March. Some saw that as disappointing in that the hoped-for rebound after the year’s disastrous start fizzled so quickly, or at least did not continue to advance.

Although readings over 50% indicate more companies are expanding instead of shrinking, manufacturers are clearly struggling to grow. The ISM index has hovered between 48% and 52% since last summer.

The sluggish ISM reading for April also suggests that scattered evidence recently of improvement among manufacturers is probably a mirage.

Others saw it as confirmation that the worst was over even if the manner of the rebound is a bit too uneven for comfort.

The battered U.S. factory sector has stabilized, though it remains far from full health.

The Institute for Supply Management on Monday said its index of manufacturing activityfell to 50.8 in April from 51.8 in March. For a second straight month, however, the measure remained above 50, the threshold that divides expansion from contraction.

Between the surveys, the ISM version suggested export activity was in process of stabilizing:

More sectors in April reported increased production and new orders compared with March, Mr. Holcomb said, offering “a broader base of growth across more industries.” The ISM’s export index rose to its highest level since November 2014.

The Markit version recorded exports instead in the other direction:

Manufacturers recorded another modest increase in overall new work at the start of the second quarter, but the rate of expansion was the weakest since December 2015. Reduced export demand had a negative influence on manufacturing order books in April, with new work from abroad decreasing at the fastest pace for nearly one-and-a-half years.

PMI’s are simply taken too literally, as if 50.1 means expansion where 49.9 indicates contraction; when in fact there really isn’t much difference at all between the two. What counts is context and trends and in the case of manufacturing in April 2016 both surveys are actually in good agreement that not much has changed at all – and that is very bad news. The rebound from January may not be much of one, which isn’t an optimistic view since what the ISM, in particular, suggested about March was only that it wasn’t as bad as either January or February.

In the context of either PMI, it seems very likely that manufacturing hasn’t really improved at all from the awful start to 2016. At best (ISM), it may not be getting significantly worse but remains dangerously depressed, while at worst (Markit) the slowdown continues still slowly dragging. The ISM declares “the worst is behind us” while Markit states, “Rather than reviving after a disappointingly weak first quarter, the data flow therefore appears to be worsening in the second quarter, raising question marks over whether GDP growth will improve on the near-stalling seen in the first three months of the year.” In other words, still abundant weakness with only disagreement about what that means.

Mainstream concern, however, is growing and beyond manufacturing. I mean that not just in terms of the economy but really in how “stimulus” is being revised. You don’t have to back that far to see all the glowing reviews of QE3 and QE4, many that were issued even before the first UST or MBS was ever purchased. Now? Central banks apparently tried to do too much on their own.

The latest to parrot the new “stimulus” consensus is Berkshire Hathaway associate Charlie Munger.

“I strongly suspect it was massively stupid for our government to rely so heavily on printing money and so lightly on fiscal stimulus and infrastructure,” Munger told CNBC’s “Squawk Box.”

“I think we would’ve been way better off if we’d used fiscal stimulus because … this [low interest rate] approach runs out of fire power,” Munger also said.

This is the same man who in 2010 told University of Michigan students that people in economic distress should just “suck it up and cope”, further saying they should “thank God” for bailouts.

“Hit the economy with enough misery and enough disruption, destroy the currency, and God knows what happens,” Munger said. “So I think when you have troubles like that you shouldn’t be bitching about a little bailout. You should have been thinking it should have been bigger.”

Germany was unable to stabilize its financial system in the 1920s, and, Munger said, “We ended up with Adolf Hitler.”

Last year in March, he declared that, “we should all be prepared for adjusting to a world that is harder.” What good are bailouts if we continually need constant “stimulus” one after another, swapping formats at regular intervals along the way? History is being rewritten before our very eyes, where monetary “stimulus” is now past its expiration and the pendulum swinging back to the fiscal side – even though it didn’t work, either. Resuscitating long lost favor for government spending only confirms that economic weakness in 2016 really is different than the usual. As I wrote early last month:

This resurrection of fiscal “stimulus” is just belated confirmation of that slowdown, paradigm shift. It further proposes that even policymakers are worried about what that might actually mean, and have no more faith in monetary policy (for good reason, I will add) to do anything about it. In that respect, the ongoing downgrade of the “new normal” is comprehensive.

Setting aside the tragic nature of all this, it is quite remarkable in terms of the economy’s ability to stay one step ahead only in the wrong direction. Just as economists and the media became used to the “new normal”, as the last of the QE’s failed to deliver anything of substance, thus hardening views about this assumed low-growth paradigm, the slowdown slowed down further. What was supposed to be slow and steady growth has instead turned into slow and steady contraction; or at the very least more a greater degree of uncertainty than at any point since 2009. Where QE was at least supposed to be supportive of the “new normal”, the next phase of the slowdown showed it didn’t really achieve much of anything good.

If the economy had remained as it was before the end of 2014, perhaps additional QE and monetary “stimulus” would still be plausible. For that change, we can find at least one small silver lining in the economy’s further weakness and uncertainty. We cannot, however, allow “them” to rewrite QE’s history and that of the Federal Reserve and its global cohort. In admitting failure, even indirectly, it must be entered in the historical ledger as unequivocally so. From that observation fruitful reform can flow. The mainstream will try to write history as if it was the economy’s fault (which Munger is now implying) all along when in instead orthodox economics failed. They keep referring to all of it as “stimulus” when in fact their own vacillations only prove none of it was.