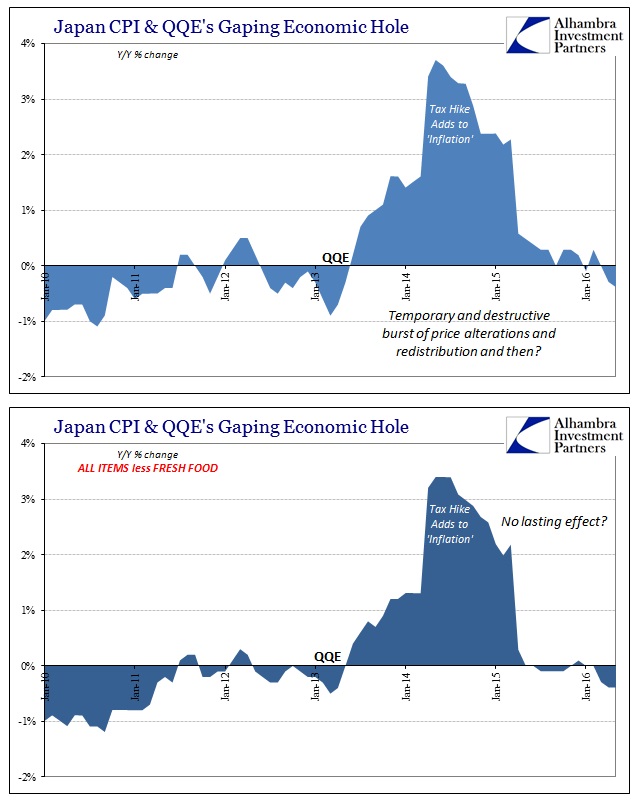

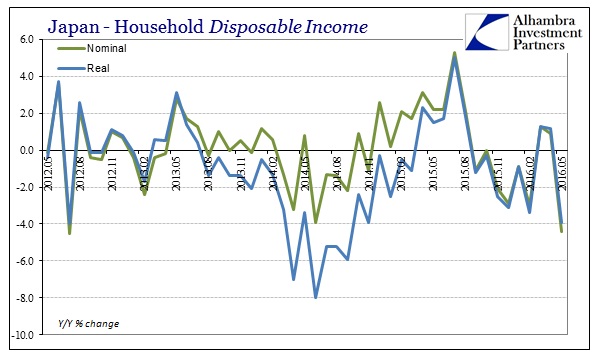

Nominal disposable income in Japan fell 4.4% year-over-year in May 2016. In what can only be a sign of the times being far too familiar in Japanese, real disposable income was thus slightly better at “only” -3.9%. For all the hundreds of trillions in new Japanese bank reserves provided by so many QE’s I have lost count, “real” in Japan means better than nominal since the CPI is negative yet again. For the month of May, the overall CPI was -0.38% less than May 2015; excluding imputed rent, the CPI was -0.48% below the same month a year earlier.

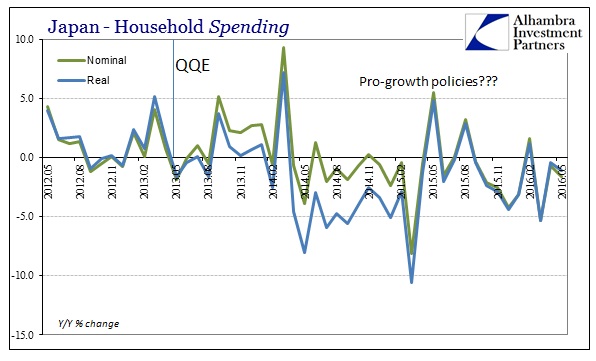

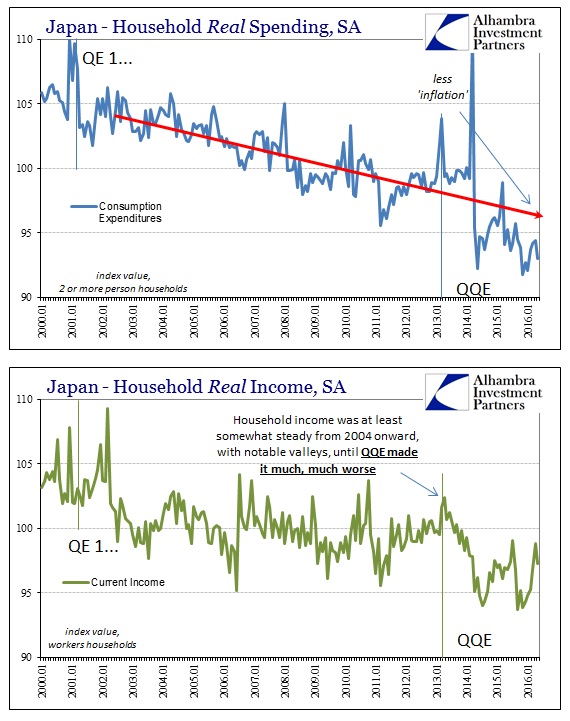

On the economic side, household spending fell in the latest update. Like DPI, nominal spending declined year-over-year by 1.6% while real household spending contracted by “only” 1.1%. In the 28 months since January 2014, real household spending has astoundingly fallen in 24 of them. Since the start of QQE in April 2013, spending in real terms is down more than 6%, while real current income is 5% lower. At this point, the fact that QQE didn’t work is a blessing since Japanese households can really bear no more of the monetary genius-ness.

But it opens markets to the distinctive shift that we have observed all over the world. If it is fair to conclude that QQE, the biggest and most impressive (in redundant mainstream and orthodox terms) monetary experiment ever unleashed, didn’t restart the Japanese economy or even lead to anything other than a small, temporary burst in the CPI, then more questions are to be raised about the basics of monetarism right down to its core. In other words, if so much “money printing” in the form of bank reserves doesn’t even affect the CPI as much as the tax hike, then it is fair to suspect whether bank reserves are actually “money printing” in the first place.

The Japanese economy itself is enough of a sample to conclude in the negative on the economic side. Because of that, doubts as to its financial elements are entirely legitimate in a way never before believed even slightly open to criticism and suspicion. Even yen and currency that were supposedly directed exclusively by the Bank of Japan and whatever its monetary policy settings have of late been contradicting in sharp contrast to recent history.

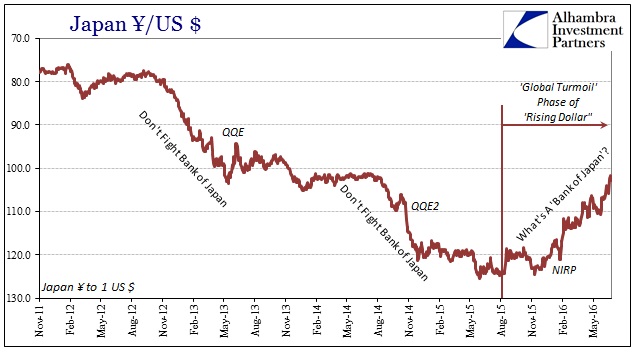

When QQE began, it was unchallenged convention that easing of any sustained kind would actually be easing. In currency terms, “money printing” leads to devaluation. The yen dutifully responded on just the whispers of possible BoJ participation in Abenomics, having started lower months before the actual transactions in bank reserves. The direction of the yen was largely unquestionable especially again in 2014 when BoJ increased its pace of reserve expansion.

“Something” changed, however, by November 2015. The yen reversed and has remained defiant. In what was really a stinging rebuke, outside of a few trading days the Japanese yen kept appreciating and ignoring entirely the institution of NIRP. In the weeks and months since, that trend has continued no matter how much talk emanates from official policy corners, both monetary and fiscal. Suddenly, it was as if monetary policy no longer existed.

The Bank of Japan, of course, is not the first central bank to find itself with such obvious impotence. There was the Bank of Switzerland in January 2015, the People’s Bank of China last August, and even the Federal Reserve really throughout all of this. The yen no longer “belongs” to the Bank of Japan, it belongs, as it really always did, to the “dollar.” In other words, what the world is finding out is just how little power central banks actually possess. When their assumed authority was just words, they were powerful institutions that markets cowered in fear over mere threats. Now that they are explicit actors, they have proven themselves as never anything more than words.

Myths die hard, but markets have caught on; that is the effect of the “rising dollar” as it spun into the first rumbling of “global turmoil” in the middle of last year. As much as monetary policies and QE’s were always exposed in the always insufficient economic responses to them, it was the warning of liquidations that filled out the catalog of debunking. Money printing didn’t affect the economy because it was never money printing to begin with; the financial implications of this are enormous – as we are finding out in especially European banks repeating what surely looks like “contagion” again.

This was all discussed in the context of Japan’s first bout of QE back in June 2003.

Governor Kohn was apparently unable to imagine how non-Japanese central bankers might also possess (if not only possess) great ability to undermine themselves and their assumed power; especially in situations where they should not be so sure what power they might actually possess in the first place, essentially the central point of this discussion in June 2003. Alan Greenspan’s warning at that meeting could easily be distilled as “make sure you can actually do what you say you can do before you actually have to do it.” Unfortunately, that would require honest assessment, which is something the Fed has demonstrated itself (over and over) never quite capable of producing.

And so the implicit regime of central bank authority which left questions about what central banks could actually do has given way to just those worst fears, an explicit regime of central bank action that has instead proven everything they can’t – which is pretty much everything. The yen’s defiance in 2016 is just the latest indication to fall on that side. Monetary policy doesn’t work because there is no money in it, and hasn’t been for a very, very long time. The world from this perspective makes a whole lot of sense, but doesn’t leave much for the future because central bankers refuse to open their eyes.

The “dollar” needs to be replaced, but it won’t be (voluntarily) because it was the real authority all those prior decades where Greenspan was thought the “maestro.” Central bankers would like nothing more than to get back to that condition, where their esteem was unchallenged and their political place unmovable. It does not matter, it appears, how many lost decades need to be spent in order to make that happen; they are quite willing to keep trying no matter how many failures in between. The rest of the world, however, can’t afford the luxury or the patience. Prolonged stagnation (at best) is socially and politically disruptive, historically leading to the worst sorts of outbreaks.

The way back to 2005 is impossible, but the more central banks attempt it the more the economy will suffer on the road to real unpleasantness. The way forward is to start over, define a new, stable global currency regime and put an end to all the myths; markets are in 2016 already partway there.