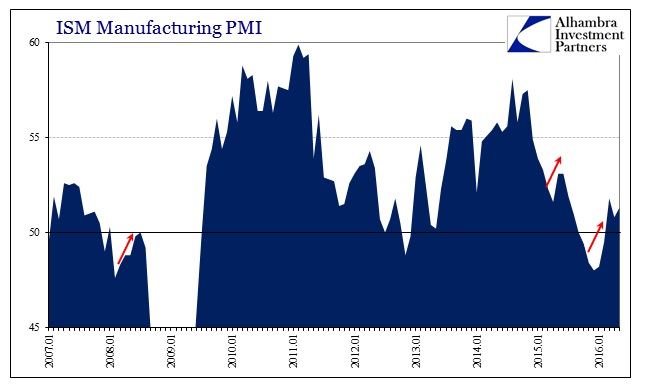

As with China’s manufacturing, so goes global manufacturing. Rather than rebounding out of 2016’s dismal start, the failure to follow through in April and now May simply proves yet again that nothing has changed. These PMI sentiment surveys are believed to be far more precise than they really are. Even though the ISM Manufacturing PMI, for example, rose slightly to 51.3 in May from 50.8 in April, that isn’t a material difference in the more appropriate wider context. In the interest of brevity, I’ll just copy what I wrote earlier today of China’s PMI’s:

The focus on 50 or not 50 is entirely misplaced; something that bears constant repetition. The ups and downs at the start of 2015 did not indicate a material change in the overall economic trend in China, so the shift from less than 50 to above 50 didn’t indicate anything other than that March and April 2015 were likely somewhat better than January and February; “better” being the operative term. Not quite bad as bad doesn’t equal good no matter which side of 50 the index falls.

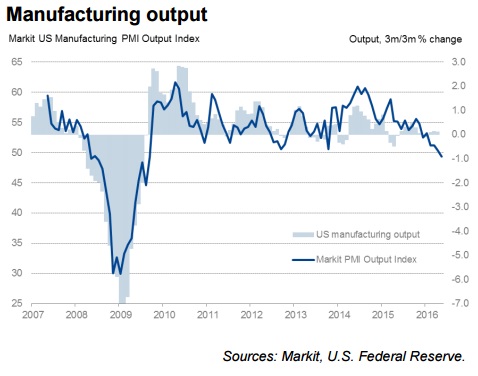

That point also applies to the Markit US Manufacturing PMI which unlike the ISM showed material deterioration especially in the current production subcomponent.

May data pointed to another loss of momentum across the U.S. manufacturing sector. New business growth eased to its weakest so far in 2016, which contributed to a decline in production volumes for the first time in over six-and-a-half years. Survey respondents noted that subdued client demand and heightened economic uncertainty had resulted in challenging trading conditions.

Above 50, below 50, the economic circumstances are the same as they have been all through this “rising dollar” period. Because it is not straight recession, economists proclaim that this is still solid if unspectacular growth when it isn’t growth at all. This is slow decay, an entirely new economic circumstance for which there is no precedence; a paradigm shift that is revealed only in bits and pieces rather than all at once in typical cyclical fashion.

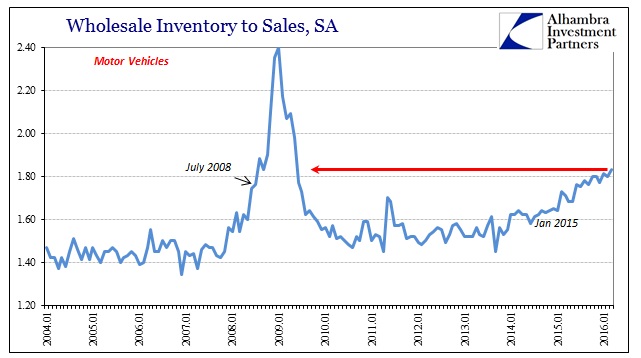

One of those “bits” was also added today, very much related to the continuing slowdown and whether it might gain a more negative slope.

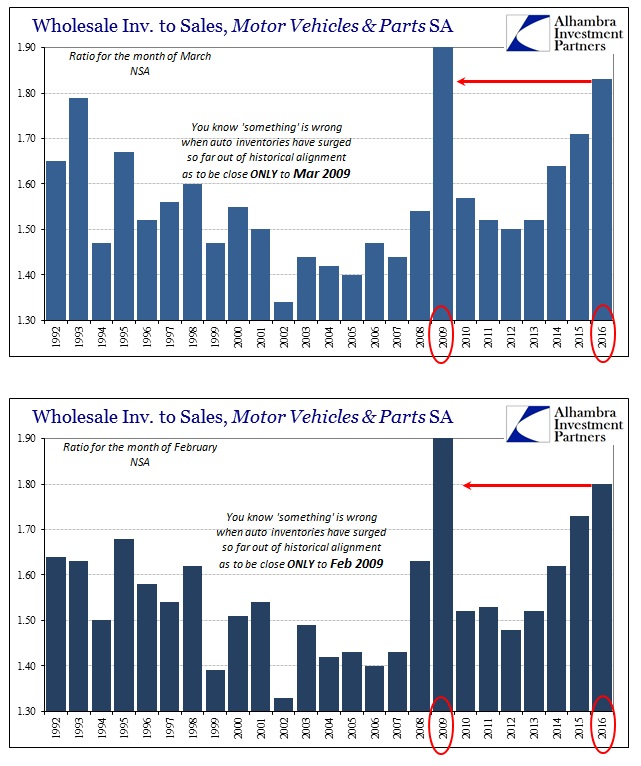

GM sales plunged 18 percent, missing estimates for a 13 percent drop, with all four brands reporting declines of at least 14 percent. Ford’s light-vehicle sales slid 6.1 percent, according to Bloomberg, compared with an average estimate for a 4.9 percent decline. GM projects a sales pace for the month that is slower than analysts had predicted.

All of the six largest carmakers were estimated to report declines for May. Even as auto sales gained in April and the U.S. consumer continues to spend, there have been signs of wavering economic confidence, and the industry may struggle to maintain its record pace. As a kickoff into summer on the back of Memorial Day weekend promotions, May is a bellwether for gauging buyer appetite.

There are calendar effects (2 fewer selling days) to take into consideration, but no matter if they were meaningful or not the pace of auto sales in May is seriously deficient just in absolute terms but far more economically menacing given rapid expansion of auto inventories since the start of 2015.

It adds up to still more negative production factors ahead even after nearly two years of them already. Because this deceleration and contraction has taken that long, it is imperceptible to the mainstream that expects everything in a straight line; leaving economists surprised when each claimed rebound is cut so short every time. The improvement in the ISM index wasn’t truly an improvement, especially since we are at least three months past the latest “transitory” weakness. Instead, it only indicates at best more of the same, including Markit’s PMI that might suggest just how far “the same” has now progressed.