On July 21, 2009, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote an op-ed published in the Wall Street Journal seeking to allay any fears over balance sheet expansion. This was all relatively new, and at that time the recovery seemed a good bet and appeared to be underway in many places. Bernanke’s goal was to soothe any fears that “inflation” would get out of control because of the FOMC’s actions in QE1 and other expansionary programs.

But as the economy recovers, banks should find more opportunities to lend out their reserves. That would produce faster growth in broad money (for example, M1 or M2) and easier credit conditions, which could ultimately result in inflationary pressures—unless we adopt countervailing policy measures. When the time comes to tighten monetary policy, we must either eliminate these large reserve balances or, if they remain, neutralize any potential undesired effects on the economy.

He argued that though he increased the “money supply” his efforts alone at the point of full recovery which he would determine would be enough to forestall any out of control price spiral. Undoubtedly his reasoning for writing this article at that moment was sound, namely that his biggest (loudest) critics were those arguing that he was trading one worst case for another; perhaps to the point, as some charged, of hyperinflationary collapse. What he put forth to defray those arguments was, however, nonsense.

We know that without fail because of what he said above – is Janet Yellen in any way considering that the Fed “must…eliminate these large reserve balances?” Not at all, in fact the settled “wisdom” of the FOMC right now is that even in the current thrust of “exit” (which the Fed can’t even get to in a straight line) the Fed’s balance sheet must at least remain constant.

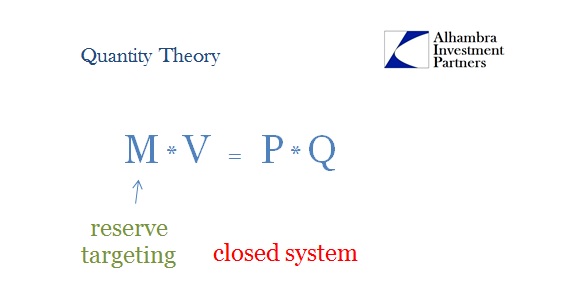

At issue is really the core of all problems. What exactly are these bank reserves? In July 2009, Bernanke was treating them as any good standing monetarist would, as if they were money even HPM (high powered money) as Milton Friedman once described. Even though the financial system had undergone a radical (shadow) transformation, the monetarists still held fast to the belief that bank reserves, and by extension the Federal Reserve, were at its center. Control lies at that point – in theory.

In November 2006, Chairman Bernanke spoke to the ECB’s Fourth Annual Central Banking Conference in Frankfurt, Germany. Given how events have transpired, what he said that day doesn’t seem to immediately fit with overall monetary policy and policy philosophy. For the Fed, policy has been very simple even though money has increasingly taken the opposite approach.

For example, in the mid-1970s, just when the FOMC began to specify money growth targets, econometric estimates of M1 money demand relationships began to break down, predicting faster money growth than was actually observed. This breakdown–dubbed “the case of the missing money” by Princeton economist Stephen Goldfeld (1976)–significantly complicated the selection of appropriate targets for money growth. Similar problems arose in the early 1980s–the period of the Volcker experiment–when the introduction of new types of bank accounts again made M1 money demand difficult to predict. Attempts to find stable relationships between M1 growth and growth in other nominal quantities were unsuccessful, and formal growth rate targets for M1 were discontinued in 1987.

The Fed responded by updating its models almost constantly, coming up with, among others, something called the “conference aggregate” specification that the Federal Reserve Board apparently still uses. They also developed P* (P-star) based on M2, projecting long-term “potential output” and velocity using the simple layout of the equation of exchange. Bernanke even went so far in his speech to note that P-star received front page attention in the New York Times.

It wasn’t enough to keep up, however, as Bernanke admitted:

Unfortunately, over the years the stability of the economic relationships based on the M2 monetary aggregate has also come into question. One such episode occurred in the early 1990s, when M2 grew much more slowly than the models predicted. Indeed, the discrepancy between actual and predicted money growth was sufficiently large that the P* model, if not subjected to judgmental adjustments, would have predicted deflation for 1991 and 1992. Experiences like this one led the FOMC to discontinue setting target ranges for M2 and other aggregates after the statutory requirement for reporting such ranges lapsed in 2000.

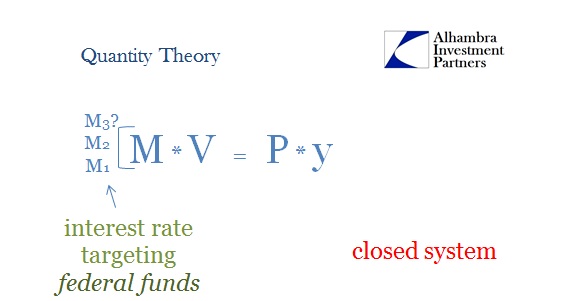

That leaves us with a conceptual gap between Bernanke relating the history of money and the breaking down of its central relationships, though in July 2009 quantity theory remained the dominant setting. The missing piece is further complicated by the Fed’s actions in early 2006 discontinuing M3 altogether, thus ending what would be a more logical progression – following M1 until innovation places more emphasis on M2; then when M2 is surpassed it stands to reason quantity theory would be more interested in M3 or even an M4, not less.

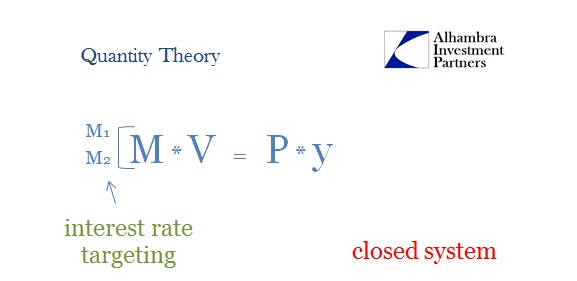

The Fed’s solution was to focus more so on “money demand” than strictly supply. That began in the 1980’s, during what Bernanke called in 2006 the “Volcker Experiment”, where the central bank began to believe that they could just bypass all nuance in money innovation by simply targeting the federal funds rate rather than some quantitative aggregate. They fully expected the result would be the same – control over a unified “M” no matter what form all the “M’s” might take that in the closed system of the US economy would act as the equation of exchange presumes.

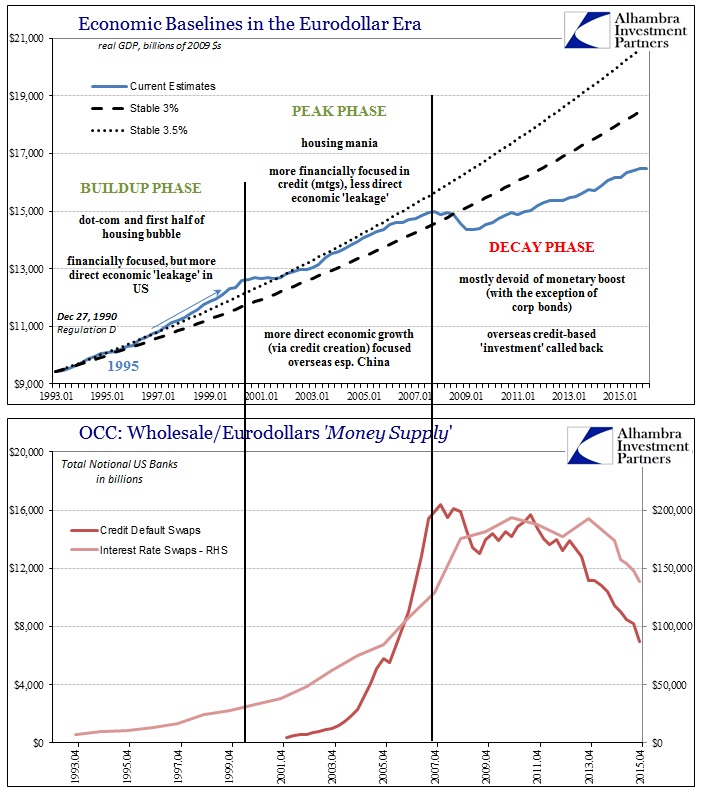

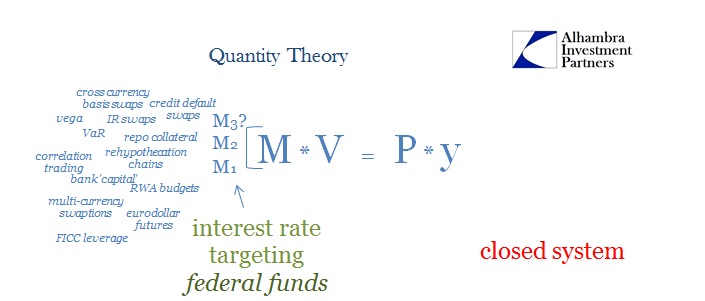

If the P* model was predicting deflation in 1991 and 1992 it was because it missed out on the great transformation of that time. The rise of “shadow banking” was coincident to the collapse in the last significant bastion of traditional banking and money – S&L’s and the thrift model. Traditional banking had already been blurred even by the S&L’s as early as the 1970’s, and indeed it was the innovations in wholesale finance that were as much to do with the S&L crisis as anything. In their place were only commercial banks that were skewing more and more to these “shadows.”

Rather than reassess, the Fed hardened its stance that targeting the federal funds rate alone would be entirely sufficient no matter how far “money” might be transformed. As Alan Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” speech in 1996 indicated, however, in practice it didn’t go so smoothly. That already suggests a lack of devotion to observation and practical operational conditions, leaving only ideology to explain the inflexibility.

As financial innovation broadened in unbelievable fashion, bringing with it the first enormous asset bubble, the Fed responded with only more interest rate targeting. As noted a few weeks ago, even at their worst moment there were only fleeting doubts about the viability of their main control theory. The end of M3 a few years later just confirmed the true basis of actual monetary policy – a curious lack of curiosity.

In truth, the eurodollar system’s expansion was as much qualitative as quantitative. I have no doubt that the Fed recognized as much but prevented itself from exploring it because it represented a mortal threat to not just monetary policy but the entire basis of any activist central bank. Shutting down M3 was supposed to encourage faith in quantity theory, as control via interest rate targeting was thus proclaimed as a comprehensive blanket so much that the Fed need not worry about the exact money details. The more the real world of especially the 2000’s denied it in practice the less the Federal Reserve (and other orthodox central banks) took interest in why that was.

Greenspan and Bernanke were forced into the “global savings glut” and “conundrum” as ridiculous excuses to try to maintain quantity theory and control as they were being empirically disproven in real time. Any unbiased examination would easily come to the conclusion that the Fed had lost jurisdiction long before the housing mania (even under the terms of quantity theory itself). It was, tragically, easily overcome not by science and deference to truth but by the lingering PR and politics of the Great “Moderation.” Nobody in the government or media questioned the maestro, even after the dot-com bust where his reputation seemed suddenly a little overdone (the idea of the “Greenspan put” survives to this day).

That was the operative theory that supported all FOMC actions starting in August 2007. From this view, it is quite easy to see why the Fed failed over and over and over again all throughout the panic. Ironically, where Bernanke noted how P* predicted deflation in the early 1990’s as traditional money supply was gravely affected by the S&L’s yielding traditional M2 to the new components of the eurodollar, here he was fifteen years later expecting no deflation at all because of how his Fed modeled the effectiveness of singular monetary control via federal funds – which meant, via quantity theory, they could confidently predict that even as late as early 2008 there wouldn’t even be recession, just a minor slowing soon forgotten. The modern shortcut was no better than the pre-modern reliance on supply targets, a fact that should have been apparent and incorporate a long time before 2008 left no doubt about it.

Despite the fact that everything went wrong at that time, including how in the worst parts of the panic the effective federal funds rate was too low not too high, they still went with QE for the recovery. Quantitative easing sounds completely different than interest rate targeting, but it is instead just the extension of it past the zero lower bound. As the term itself announces, it is still the embedded philosophy of quantity theory.

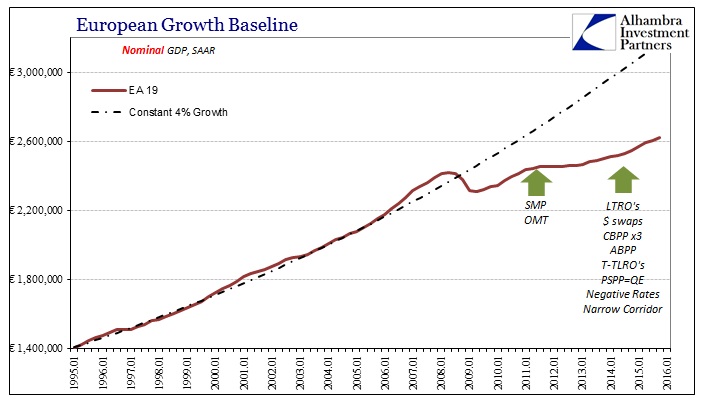

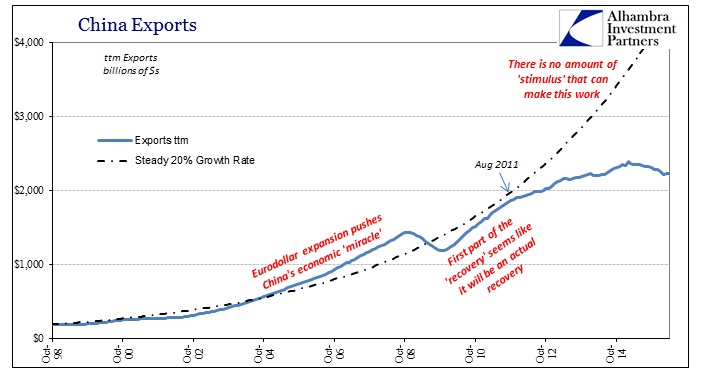

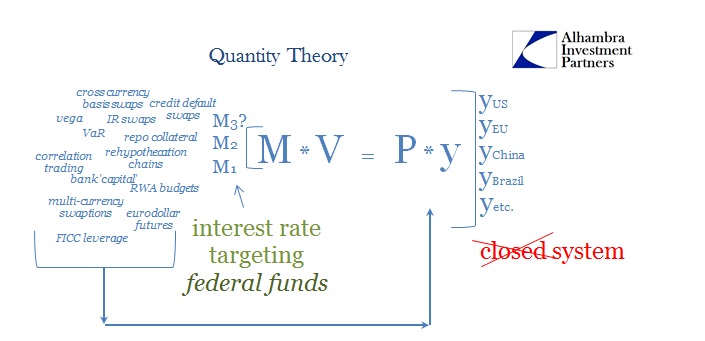

Not only was the philosophy missing badly in terms of the money component, it was falling apart on the other side of the equation as well. The whole world followed the true state of global “money” as the eurodollar system magnified its negative feedbacks to all parts of the global economy. Where economists in 2008 really believe in “decoupling”, by early 2009 there wasn’t a place to be spared. The US system was not closed as if the only part operating with dollars, it was easily observed that as the true “dollar” went so too did everyone else. It was a synchronized economic catastrophe that barely ever noticed federal funds or QE. We are doomed to repeat history because nobody was listening the first time, so the events of the “rising dollar” since June 2014 have been to reinforce all the evident problems of the monetary orthodoxy.

As Bernanke’s 2006 speech makes clear, the Fed has been aware of most of these monetary differences and innovations the whole time. I think it is easy to understand why they never followed through to full incorporation because doing so would mean admitting that quantity theory was no longer valid and thus economic control through monetary influence was this whole time impossible. The whole of the 21st century so far is, unfortunately, an abject lesson on exactly that point. From a purely political perspective, it was better to barely acknowledge the world was changing if only to then downplay it in favor of the magic wand of federal funds targets.

Though there were these constant discrepancies, economists did much more than cross their fingers and hope for the best, as the Fed and all orthodox central banks spent enormous effort in coming up with math and regressions as to why interest rate targeting really was as powerful as they desired it to be (global savings glut being one such attempt). But as 2008 showed, all that academic expenditure was worth nothing and really just amounted to economists telling themselves with numbers (full of recency bias) what they most wanted to hear. So the Fed still does QE’s, as the ECB or Bank of Japan, and no one can quite find any trace of them. It’s as if they were never there and central banks held (hold) so little if any control, so much has the world’s economic trajectory bent more and more tragically out of shape.

Paraphrasing Milton’s Paradise Lost, economists seem utterly determined to reign over economic wreckage than properly redefine money and serve in the real recovery. They have no other actual excuse – it’s been all right there in front of them from the very start. The recovery is and always has been political.