Over the years, the “wealth effect” has been taken as a core component of monetary policy. Central bankers will not admit it, of course, but particularly stock prices are a central element of their strategy. It almost has to be that way given that the modern version of econometrics applies rational expectations theory as a literal condition. Since expectations form the basis of orthodox understanding about how an economy works and why it changes, the biggest effects, economists believe, of any policy are achieved when they impact consumer, financial, or business expectations the most.

So it is with record stock prices. By the nature of the Great Recession in terms of its depth (not that it was actually a recession), monetary policy was hugely constrained in how it might respond. As then-former Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote in November 2010 explaining why QE2 was in his view necessary:

This approach eased financial conditions in the past and, so far, looks to be effective again. Stock prices rose and long-term interest rates fell when investors began to anticipate the most recent action. Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.

You should notice the weasel word in his phrasing: “can” also spur spending. The reality is that economists don’t really understand how this might actually work. As with all statistically-based models, there wasn’t a whole lot of data to fill out all possible ranges of scenarios in order to produce truly robust models of correlations between asset prices and consumer spending under all conditions. Most of the econometric work was taken from the 1980’s and 1990’s where asset prices were rising and so was spending. Rather than view that as perhaps an accident of mere circumstances unique to those times, this “wealth effect” was instead, as usual, given status as a core economic “truth.”

The central myth of all central banking is that if it happened during the Great “Moderation” central banks could make it happen again by mere policy. Understanding, then, actual money evolution and potential would have disproved the idea at its very start.

When Janet Yellen, for instance, was speaking in Portland, OR, in July 2005 at a time when the housing version of the “wealth effect” was increasingly questioned not by policymakers but more so from the bottom up (common sense), she, as Bernanke and Greenspan, foresaw little difficulty even in what might be the worst circumstances. Officials believed they had a handle on the “wealth effect” should such a low probability event (in her view) occur, whereby the potential damage would be limited. Even where housing prices “might” decline by 25%, the math claimed:

First, there would be an effect on consumers’ wealth. With housing wealth nearing $18 trillion today, such a drop in house prices would extinguish about $4½ trillion of household wealth—equal to about 38 percent of GDP. Standard estimates suggest that for each dollar of wealth lost, households tend to cut back on spending by around 3½ cents. This amounts to a decrease in consumer spending of about 1¼ percent of GDP.

This was entirely manageable and thus no cause for any concern at all. She even uses that word:

How manageable would this scenario be? Like the wealth effect, these added interest-rate effects operate with a lag, so, again, there probably would be time for monetary policy to respond by lowering short-term interest rates. This obviously would not be a “slam dunk,” but in many circumstances it would seem manageable.

Even though she recognizes after this statement the complications and dangers of financial fallout from housing, she again dismisses it because “the financial system and consumers appear to be in reasonably good shape to handle the situation.” As all other economists, she was proved disastrously inept just two years after making this claim when the monetary system dictated to the financial system how this was really going to go; and it wasn’t anything like any econometric model ever anticipated. In fact, the regressions all believed such a scenario practically impossible; at best no more than a “trivial” concern.

Though that was her way of relating the downside, incorrect in every way possible, the “wealth effect” remained, as Bernanke wrote, an article of faith if maybe not so precisely calibrated in the aftermath. But no matter how high especially stock prices go, there is no wealth effect – NONE.

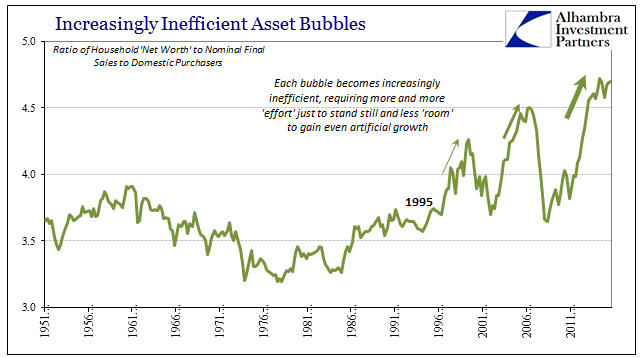

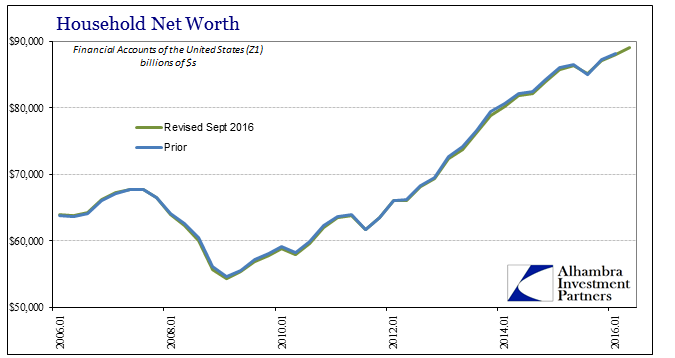

The Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States (formerly Flow of Funds, still Z1) shows that there is and has been restoration in at leatst the first part, the “wealth.” Household net worth jumped to a record high $89 trillion in Q2 2016, up from $88 trillion in Q1and $54.4 trillion at the depths of the monetary crisis in 2009. Yet, as we know all-too-well, that hasn’t led to any of the effects Chairman Bernanke described in his justification of QE2 (let alone the third then the fourth). Instead, when comparing “wealth” versus spending there is considerably less relationship just as paper wealth builds to ever higher record levels.

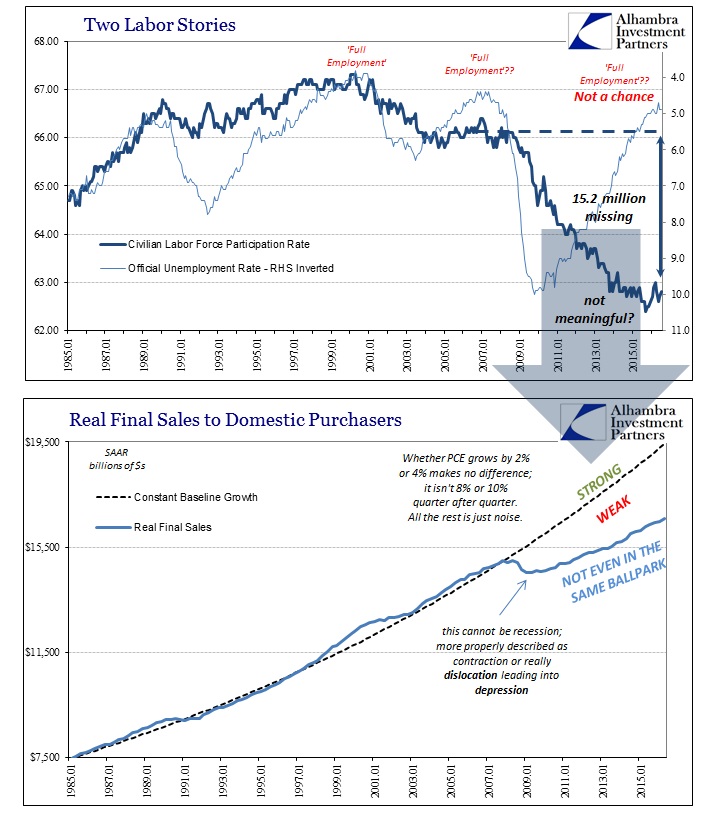

No direct effect and no spillovers, facts we can easily observe from especially the labor market and its more determined relationship with spending.

Stock prices and paper wealth are ephemeral if considered at all since they largely only apply toward the top of the wealth spectrum and there is no “trickle down” without monetary growth. Thus, it doesn’t matter record stock prices compared to what economists call “gloom” since all that is actually just plain reality.

In the world of the real, businesses don’t invest because their revenues don’t expand; end of story. Revenues aren’t expanding because businesses won’t hire no matter what the unemployment rate says; end of story. This was all, of course, one of the factors that quantitative easing was meant specifically to address – derived from the statistically modeled understanding of expectations rather than the actual conditions of them. The “wealth effect” was supposed to break the economy out of any gloom, as rising asset prices, especially the repeated and emphasized “record highs” of stocks, bonds, or anything in between, would surely negate any immediate “gloom” as it rolled over into expectations of an impeccable future.

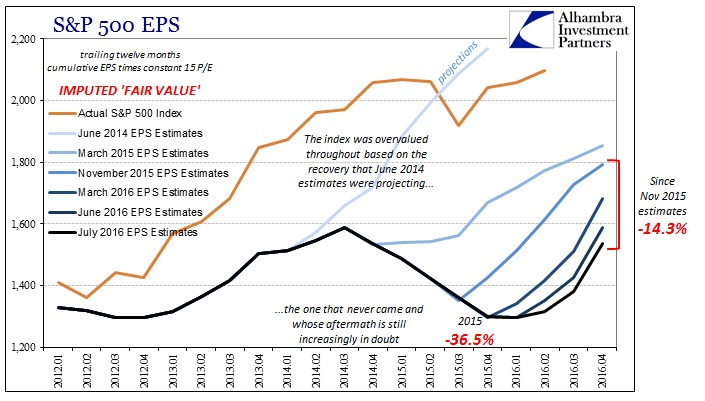

Given now the disparity between the future stock prices have been priced for and the reality of that future particularly over the past few years, record high asset prices wouldn’t even accomplish all that much anymore even if a “wealth effect” were suddenly more potent. The track record of record high stock prices is rapidly approaching the dismal performance of Janet Yellen, Ben Bernanke, and all economists when they speak of them.

The last nearly decade has disproved so many orthodox myths, yet they persist in the media and in econometrics because statistical mathematics is given the same deference as if it was actual science. It isn’t. The failure of the “wealth effect” is but another in a long list of irrefutable evidence that they really don’t know what they are doing. But “we” let them continue to do it anyway.