By Ken Brown at the Wall Street Journal

Markets are teetering in large part because the rally we’ve just witnessed was so weird.

That rally reversed a beginning-of-the-year selloff and wiped away worries about China, tighter financial conditions, weak economic growth and collapsing commodity prices.

Yet it was full of contradictions and confusion. How often do stocks, government bonds and gold rally together? Why did the yen rise even as the Japanese economy weakened? How come oil rose 67% while producers struggled to find places to store excess supply?

Blame it on years of weak economic growth and distortions caused by central-bank stimulus. The normal rules of investing have been upended, causing bond markets to predict slowdowns while stocks expect recoveries and currencies move on their own, increasingly untethered from economic fundamentals or central-bank direction.

This makes it especially difficult to predict what’s next. One scenario is that markets start believing that the U.S. Federal Reserve is more serious about raising rates, which would send the dollar higher and hit commodities, bonds, China and emerging markets.

Fundamentals in many places are weak or have been propped up by successive rounds of stimulus. To the extent the market’s rally was based on those fundamentals, a shift in government policy, such as the expected slowdown in China’s credit boom, could also hit markets.

Here’s a walk through some of the risks and contradictions in major markets:

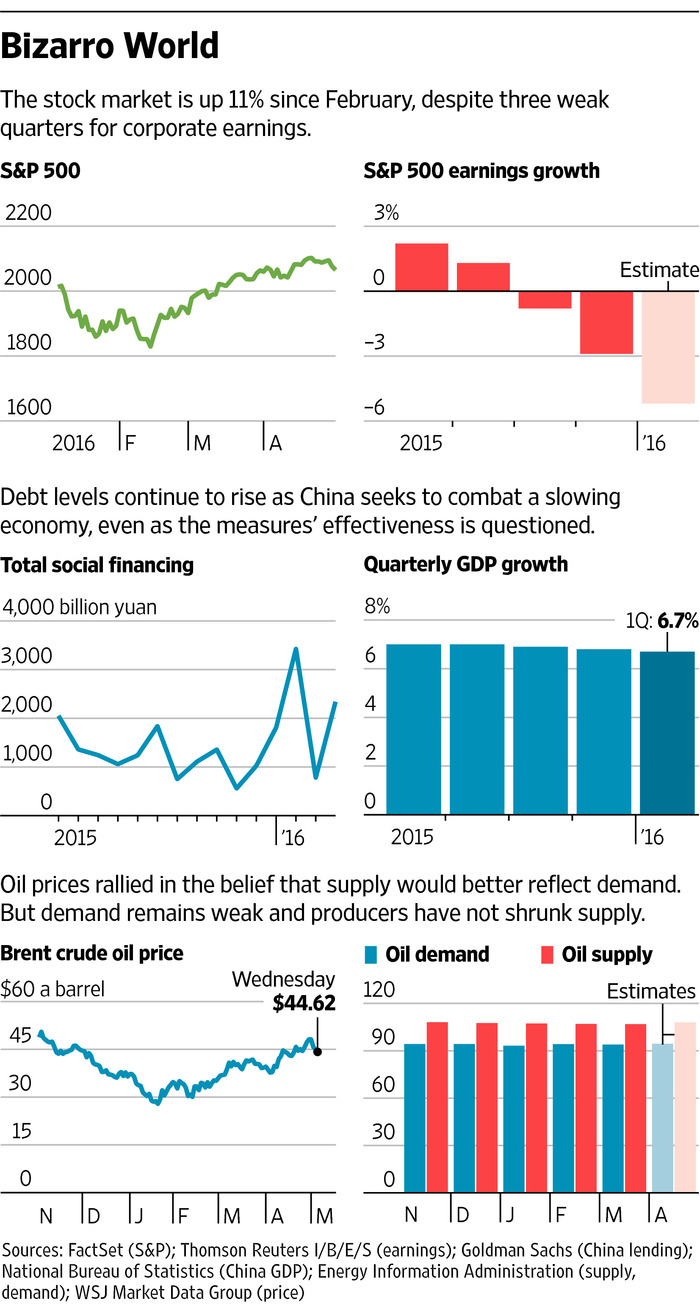

Stocks: The U.S. stock market is up 11% from its February bottom and trades at a forward price-to-earnings ratio of 18, slightly below its valuation a year ago. That is, as bankers like to say, a full and fair price, given we have just finished the third straight quarter of down or flat earnings per share. True, earnings could pick back up with higher energy prices and a weaker dollar but there is little chance of a strong jump.

One positive is that companies are paying shareholders through rising dividends and share buybacks at a time when yield is so hard to get. The flip side is companies are borrowing but aren’t investing, weakening future earnings potential that would justify the current valuation.

Bonds: The great justification for expensive stocks is low bond yields. They got lower on Tuesday when Australia cut rates and global bonds rallied, pushing the 10-year Treasury yield down to 1.8%, not far from its low in February.

Central-bank buying has pushed down yields on government bonds and squeezed spreads, which doesn’t happen in normal times. Markets aren’t expecting any serious tightening this year. If they are wrong, that is where the biggest losses could be.

Currencies: These markets have also been heavily distorted by central-bank action. The question here is have central banks lost control. The rise of the yen when Japan went to negative interest rates, and the further rise when it did nothing last week, are worrisome.

Oil: Prices have rebounded 67% from their low on the idea that supply would start to slightly resemble demand. That hasn’t happened. There is so much supply that producers are running out of places to put it. Oil led the market up and appears to be leading it down, falling more than 6% from its recent high.

The Phds at Bernstein research—there are three of them on the energy team—found that even as prices tumbled, shale-oil producers kept drilling. Companies completed 1,500 wells in the Upper Midwest’s Bakken Shale last year, although drilling fell as the year went on. That kept the decline in production to just 3%. Combined with an OPEC that can’t agree to cut production, it means supply won’t likely fall a lot.

China: There aren’t many problems that $1 trillion can’t fix. That was the amount of credit issued in China in the first quarter by Chinese banks and shadow banks.

The lending is part of China’s big stimulus effort to keep the economy growing according to plan while it ponders reform. If you look at what the International Monetary Fund calls the augmented fiscal deficit, which is the fiscal deficit plus the money the government spends from its bank accounts, plus what local governments typically spend, the number has hit 10% of gross domestic product in some months recently, according to Goldman Sachs.

The borrowing spree not only adds to concerns about China’s debt levels, it may not be working, either. China contributed to this week’s selloff with weak manufacturing data, which sent metals prices down. Australia’s interest-rate cut was essentially an acknowledgment that its commodities exports to China weren’t rebounding any time soon.

Analysts expect the Chinese stimulus to ease later this year. That would make any effort to shut down zombie companies harder. And if the dollar rebounds, it would put further pressure on Chinese growth.

China started the last selloff, and it could start the next one. Central banks could ease further but they may not be able to bail out markets like they did earlier this year.

The calm of the last two months appears unlikely to last.

Source: Today’s Markets: A Place Where Nothing Makes Sense – the Wall Street Journal