Turkey’s Crackdown Sweeps Through Business and Finance, Imperiling the Economy

Investors who saw Turkey as a free-market beacon fear its president’s focus on rooting out internal enemies endangers financial institutions and trust in its economic stewardship

By YELIZ CANDEMIR

Updated Nov. 3, 2016 1:25 p.m. ET

Istanbul’s tightknit finance community first felt the chill of Turkey’s post-coup crackdown in late July when a senior banker was hit with a criminal complaint and stripped of his license.

Fear spread when regulators started forcing banks to hand over internal client communications, according to several people familiar with the moves.

Then, over succeeding weeks, Turkish authorities took over 496 companies, some with publicly held units, citing a hunt for coup plotters.

The moves mark a sharp reversal for a country long seen as a free-market beacon among emerging nations, thanks to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s embrace of pro-business policies. Turkey attracted international investors in part because of the government’s lack of meddling.

Now, investors and businesspeople say Mr. Erdogan’s relentless focus on rooting out perceived internal enemies, coupled with a consolidation of power under an emergency decree, imperil domestic financial institutions and trust in the country’s $720 billion economy. Turkey’s Parliament, dominated by Mr. Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party, or AKP, recently extended emergency powers for another three months.

“The risks are disproportionately high,” said Michael Harris, London-based global head of research at investment bank Renaissance Capital, who is recommending clients divest from Turkey. “A lot of foreign investors are understandably jittery in this environment and see these developments with worry.”

One of Turkey’s top corporate law firms was shut down following a police raid that investigators described as part of their investigation of the July 15 attempted coup. Clients are left trying to secure what they thought had been confidential corporate information.

Purges at the Capital Markets Board, meanwhile, paralyzed Turkey’s financial regulator and prevented voting on at least 25 planned debt and capital issuances for 2 1/2 months until the government appointed new board members.

In such as tense atmosphere, stern words from the top can be enough to change business behavior. “There’s a disagreement between me and bankers on interest rates,” Mr. Erdogan said in an August speech. “If they try to turn [their] strength into an opportunity at a time like this, they’ll find us against them.” A dozen banks soon announced they were lowering mortgage rates.

Turkey’s economy is feeling the post-coup moves, which include tens of thousands of arrests. Its tourist industry had already been battered by a series of terrorist incidents. Moody’s Investors Service this fall cut its rating on Turkish government bonds to below investment grade, matching S&P’s long-held view. One reason Moody’s cited was concerns about the rule of law.

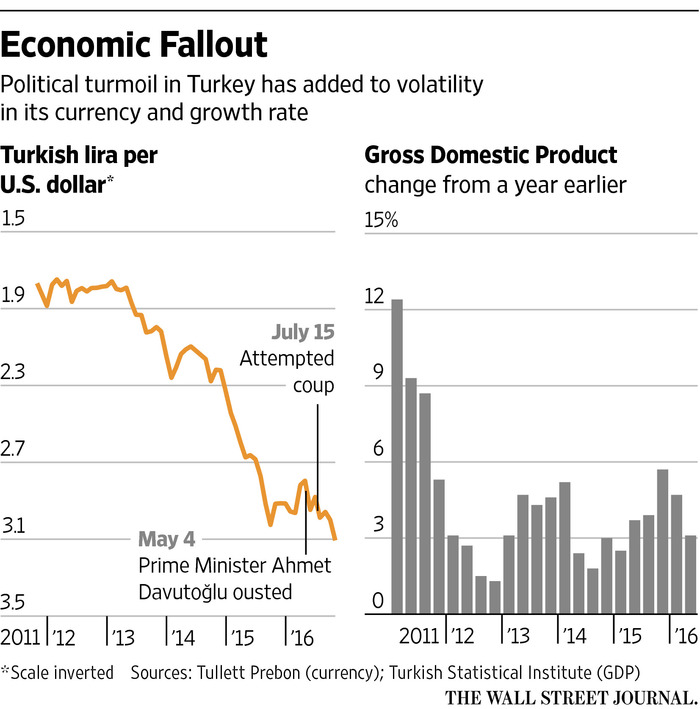

The Turkish lira hit a record low against the U.S. dollar in recent weeks. Assets managed by Turkey-focused equity funds have fallen by two thirds from their peak in 2013, falling from $3.7 billion to $1.3 billion at the end of September, according to data provider EPFR Global.

Economic growth is still strong by international standards but slowed to a 3.1% annual rate in the second quarter, from 4.7% in the first. The government revised its growth projection for next year to 4.4% from 5%. The International Monetary Fund pegs it at 3%.

Several Turkish government ministers said the economy remains healthy, citing growth, declining government debt and a commitment by the ruling party to structural changes such as trying to boost domestic savings.

“Cut the rating as much as you want—this is not the reality of Turkey,” Mr. Erdogan said in a speech shortly after the move by Moody’s. “Turkey continues its investments and development.” A government bond issue in October drew strong demand, the treasury said.

Deputy Prime Minister Nurettin Canikli said the coup attempt hasn’t hurt the economy or foreign investment, and that any negative sentiment “is not supported by real data.” The minister also rejected criticism that the Turkish government has interfered with the free market, saying instead that timely government action since the coup has helped bolster the economy.

The failed July coup took more than 270 lives during a night of terror that included jet fighters attacking parliament and crowds of civilians, while commandos tried to capture or kill Mr. Erdogan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim.

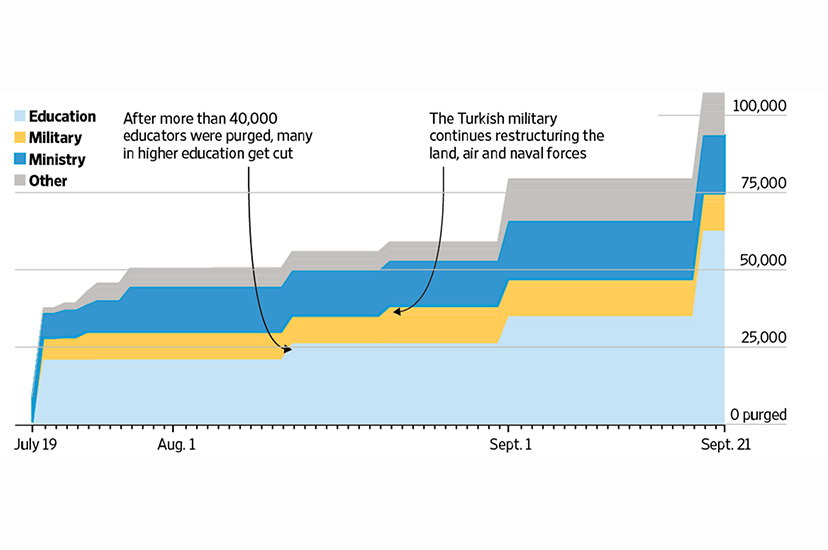

In subsequent purges of the military, civil service and political opposition, more than 36,000 Turks have been arrested, according to state-run Anadolu news agency, while investigations of their possible roles in the failed coup continue.

In the finance sector, the purge has claimed 116 employees from the banking regulator, at least 30 from the Capital Markets Board and more than 1,500 from the Finance Ministry, according to government officials. These people, some fired and some suspended, are suspected of supporting the man the government accuses of masterminding the revolt— Fethullah Gulen, a U.S.-based imam who denies any involvement.

Mr. Erdogan and Mr. Gulen worked in tandem for years to break the power monopoly that a secular, pro-military elite held for decades. Mr. Gulen didn’t have a formal role in politics; his followers worked in business and the civil service, and they supported Mr. Erdogan’s party, the AKP, once it came to power in 2002.

The alliance frayed publicly in 2013. More recently, the government has dubbed Mr. Gulen as akin to a cult leader, manipulating followers to use their businesses and civil-service jobs to undermine a democratically elected parliament. Mr. Gulen has denied any wrongdoing.

More recently, the government opened criminal cases against Mr. Gulen himself. In one confidential prosecution reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, an indictment argues that a drawing of Halley’s comet on Turkish bank notes shows the imam’s malign influence over the central bank, because the comet is allegedly a secret sign to Gulen followers. The central bank declined to comment.

Mr. Gulen, who moved to the U.S. in 1999, isn’t mounting a defense in these cases, contending the charges are politically motivated. Yuksel Alp Aslandogan, executive director of a Gulen-affiliated nonprofit in New York called Alliance for Shared Values, called the comet allegation “ridiculous.”

Mr. Aslandogan has said Mr. Gulen’s followers are committed to political change in Turkey via the rule of law. Turkey has long sought Mr. Gulen’s extradition from the U.S., a request Washington says it is reviewing.

A Turkish law that predated the Gulen-Erdogan falling-out bans the dissemination of malicious information aimed at influencing markets or investors. The law carries a penalty of up to five years in prison, and one person close to Turkish finance said it long hung like a sword of Damocles over the industry.

After the July rebellion, the sword dropped.

The Capital Markets Board said on July 27 it was purging some of its members. A day earlier, it asked prosecutors to mount a criminal investigation of the head of research at Ak Investment, a unit of Turkey’s fourth-largest bank by assets, Akbank TAS, for insulting Mr. Erdogan and state institutions. The board rescinded the banker’s license for failing to “fulfill his responsibilities.”

Government officials had been infuriated, according to one person close to the finance industry, by a client note the banker sent describing theories of how the failed coup came about, including a rumor the president knew about it and let it happen to grab more power.

The Capital Markets Board didn’t respond to a request for comment, nor did the fired banker, Mert Ulker. Ak Investment declined to comment.

Several brokers and analysts in Turkey said the chill has caused them to censor their reports. One European fund manager said he canceled his subscriptions to Turkish brokerage research because it started to read like government news releases.

Political influence has become more apparent at institutions such as the central bank. Mr. Erdogan has called for repeated interest-rate cuts by the bank to underpin growth, and for seven months the bank did cut rates. Then in October, citing a currency trading near its weakest ever level, the central bank stopped. It did so one day after Mr. Erdogan’s chief economic adviser said publicly it would be all right for the bank to “skip this month.” The central bank declined to comment.

The sweeping expropriation of Turkish companies has come in waves. One of the biggest came on Sept. 9, when the government published a decree seizing the assets of two family-controlled conglomerates with about $2 billion in annual revenue apiece. The families that head them have long been under investigation on suspicion of links to Mr. Gulen, but not tried or convicted.

One company, Koza Ipek Holding, controls Turkey’s largest gold miner, publicly traded Koza Altin İsletmeleri A.S. Its chairman, Akin Ipek, has been fighting in domestic and international courts since last fall against an investigation of alleged links between his business and the Gulen movement. In an interview, Mr. Ipek denied any wrongdoing and called the seizure a step to destroy his companies.

“They accuse me, my brother, my sister and my mother, who is over 70 years old, of being members of a terrorist organization,” Mr. Ipek said. The family members “have not done this, or even purposely hurt anyone’s feelings, anytime in their lives.”

Mr. Ipek wasn’t in Turkey before the coup attempt took place and is at large. In late October, the government offered a reward for information leading to his arrest.

The government put assets of the seized companies under control of an agency known by the initials TMSF. Some will be sold off after a tender process, the agency’s president has said, with the rights of company owners protected if they are found not guilty.

“There are some companies that are directly linked to the Gulen movement, so perhaps we will sell them first,” said the official, Şakir Ercan Gul.

Mr. Canikli, the deputy prime minister, said TMSF management has helped stem losses and boost the companies’ share prices. He didn’t specify which companies he was referring to. “We have protected the rights of international investors through these interventions,” he said.

A company owned by a progovernment businessman recently said it is negotiating with TMSF to buy the shares of Koza Ipek.

At the other seized conglomerate, Boydak Holding, which has chemical, steel and energy subsidiaries, Chief Executive Memduh Boydak and Chairman Haci Boydak were arrested in March but haven’t faced trials. Neither could be reached for comment. Haci Boydak said in a July written statement that the family and their companies have no link to the Gulen network.

State-owned Turkish Airlines dismissed 211 staff members for reasons including suspected links to the Gulen movement. Turk Telekomunikasyon AS, the country’s largest landline operator and Internet-service provider, said two senior executives have resigned after being detained as part of the anti-Gulen probe. Neither Turkish Airlines nor Turk Telekom responded to requests for comment.

As for the law firm that was raided by police after the failed coup, called Yuksel Karkin Kucuk, its office telephones now go unanswered.

—Margaret Coker and Georgi Kantchev contributed to this article.

Original article: Turkey’s Crackdown Sweeps Through Business and Finance, Imperiling the Economy