Janet Yellen’s testimony concluded, no one gets any more clarity about what the FOMC actually thinks. However, that itself is in one sense an indication as she vacillated a little too much about making a firm commitment to either the recovery or “transitory” oil prices. QE3 ended months ago and we are seven years into this thing already, but there is still debate about whether or not the economy has taken full form despite the presence of four QE’s and annual assurances they have worked.

What that may amount to is there are far more concerns than there are “supposed” to be at this point.

Analysts said the testimony did little to nail down the likely date of a rate hike, with her testimony and answers to questions veering between confidence in a “solid” recovery and continuing concerns about weak wages and other signs the labor market is not fully healthy.

Fed Chairs are known for the ability to say nothing while saying a lot, obfuscation being the primary job qualification, but we are not talking about a minor adjustment in the fed funds target from 4% to 4.25% during an otherwise solid growth state. Those downside concerns are not what was supposed to accompany the dramatic decline in the unemployment rate. Orthodox economics posits a robust and direct relationship between the unemployment rate and levels of spending and economy, but the lack of wage growth has clearly prevented any proportionality, thwarting Yellen’s best confidence.

Worse, however, is that such a pitiful condition is emblematic of other economies (as if they were separated meaningfully at the margins, including global finance) treading similar rough spells.

But the lack of inflation has made some Fed policymakers hesitant to commit to raising rates until they are more certain the United States is not headed down the same path as Europe or Japan, mature industrial economies that are struggling to maintain growth.

TV economists are apparently struggling with Yellen’s struggles, somehow justifying that the economy in her mind is somehow the economy in fact where no amount of contradictory assessments can have any improvement upon the interpretation of the unemployment rate alone.

The Pundits (Liesman) are suggesting Janet feels the economy is strong but that the “data just isn’t cooperating”. What does that even mean??

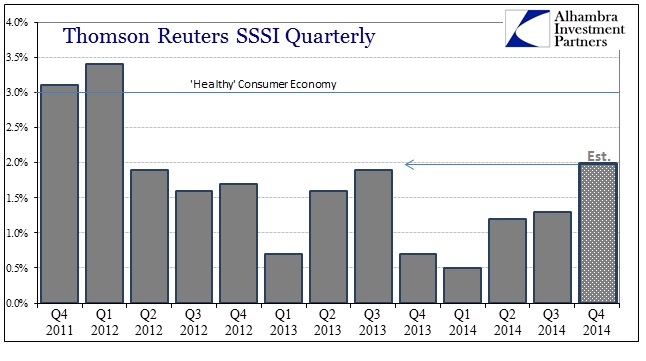

That might be the perfect encapsulation of 2015, as so far the data has been even more atrocious than the Polar Vortex vexation of winter 2014. Despite the huge run in the Establishment Survey job count, revised significantly upward of course, spending remains mired at recessionary levels. The Thomson Reuters index of same store sales (SSSI) grew at 2% (estimated) in Q4, which was an improvement upon immediately prior quarters, but still does not represent a meaningful abandonment of the current rut – one that increasingly is worn down by continued household attrition.

If the best jobs market in decades could only get sales activity to an equivalent position with the middle of 2013, and still only slightly more than half of 2012, then there truly is “something” holding the economy back. But in relatively where 2% might look to be a success in comparison to the disaster of last year, January so far puts the economy right back into those disaster-levels of activity. The SSSI (monthly) for January was actually significantly below even January 2014.

The SSS is expected to post a 2.6% gain in January 2015, down from the actual 3.1% increase recorded a year ago. Excluding the drugstore sector, the SSS growth rate is seen as dropping to 1.1%, below the actual 3.6% result posted in January 2014.

The twin “tailwinds” of job growth and collapsing energy prices were supposed to be driving consumer spending, where at least households would take money previously spent on gasoline and spend it elsewhere. That just hasn’t happened, as Costco’s January same store sales show too well – the retailer was supposed to report +1.2% in same store sales in January, but came in with 0.0% instead. A good portion of that were lower gasoline sales, but if orthodox theory about the “gas effect” was correct consumers would have shifted from gas to other items. Instead, they pocketed the gas “savings” after taking a more than a little off December spending (matching what the last two deplorable retail sales reports suggested).

With January marking the end of retailers’ Q4, it looks increasingly like that 2% may have to come back down once again – and there has curiously been no published guidance from Thomson Reuters about what Q1 might look like. Struggles in the retail sector are not unique, as revenue estimates (according to FactSet) for the S&P 500 are now negative for 2015, and valuations are getting more and more “stretched.”

Back on December 31, the forward 12-month P/E ratio was 16.2. Since this date, the price of the S&P 500 has increased by 1.9% (to 2097.45 from 2058.90), while the forward 12-month EPS estimate has decreased by 3.3% (to $122.72 from $126.90). Thus, both the increase in the “P” and the drop in the “E” have driven the increase in the P/E ratio to 17.1 today from 16.2 at the start of the first quarter.

That too confirms that the Fed may be more conflicted about the economy than they “allow themselves” to confirm in public. That is especially true as they continue to refer to “stretched equity valuations” and “valuation pressures” as a potential problem. If the economy was about to take off in a new period of robust and sustained growth, equity valuations would be the least of concerns as fast rising earnings would undercut valuations back toward more historical levels. Indeed, that is what convention posits about stocks to begin with, as a discounting mechanism for future revenue streams.

Those notions were highly disabused in October 2007 just as April 2000 – what was the S&P 500 at then-records telling us about growth prospects in each case? That was clearly “forgotten” by financialisms in the current age, but in a strange twist the Fed seems to remember at least the ambiguity.

Of course, the “dollar” will get the blame for 2015’s so far solemnity, which provides only a distraction against Yellen’s irresolution. Try as she might, speaking about how the growing economy will bring oil prices back up (without recognizing the reciprocal about how oil prices got down to begin with), the relationship of the “dollar” to the economy under these conditions more than suggests startling difficulty rather than raptured hope. While outwardly and publicly Wall Street and the big banks have agreed and parroted her most positive assessments, internally they are doing the exact opposite – on both liquidity counts and deepening economic concern.

All this is to say, that the “data won’t cooperate” and that I think Yellen and the FOMC are getting more and more worried about it. It’s one thing for markets to hiccup here and there, but the persistence in household malaise and financial distemper is serious, and it really shouldn’t be by now.