Alan Greenspan is confused – again. The man who admitted to the world a decade ago he didn’t know much if anything about interest rates is now trying to change that reputation by suggesting yet again interest rates are set to rise. In testimony before Congress in February 2005, the then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve actually said:

For the moment, the broadly unanticipated behavior of world bond markets remains a conundrum. Bond price movements may be a short-term aberration, but it will be some time before we are able to better judge the forces underlying recent experience.

To an economist, it was a “conundrum” especially where econometrics and statistics and take the dominant view (if it can be called that). That is one facet to the Greenspan story that is so odd yet so compelling in all the wrong ways. Though he was an economist by schooling, he had more practical experience in the “real” world. He served on boards of such illustrious companies as Alcoa, General Foods, even Mobil. But he was also a director for JP Morgan and Morgan Guaranty.

He should have known better, as his infamous 1966 essay on gold reveals. Thus, we can reasonably assume that what transformed his worldview was not economics (small “e”) but rather power. Not only had he been appointed to major corporate boards, he was heavily involved in politics, including the kinds that are the stuff of conspiracy theories.

By 1995, as Fed Chairman, Greenspan was widely and wildly credited as guiding the US economy through what he claimed was an existential crisis with the Savings & Loan industry bust. Though George HW Bush would blame Greenspan’s Fed in part for his 1992 election lost because of the first “jobless recovery” (a major clue no economist or policymaker investigated honestly), by the middle 1990’s it was believed he had created the recovery itself and then tamed it when he raised rates in 1994 and engineered what many still call a “soft landing.” There have been many who have been dubbed the “bond market king”, but for a long time Dr. Greenspan’s status in that regard was a cut above.

His confusion and “conundrum” in the 21st century belies the reputation that had been given him in the 20th. The US (and global) economy of the middle 1990’s didn’t bother about rate hikes because there were other processes at work, especially with the S&L’s no longer a further restraint on finance (yes, restraint). With traditional banking all but relegated to second tier status, wholesale finance of the eurodollar had been given an unrestricted path to all marginal growth – money as well as credit.

And Alan Greenspan knew it, or at least he knew of it and what it was doing. Many times during this period he would acknowledge the changing nature of money including in his “irrational exuberance” speech. By the dawn of the new millennium, that’s all there was – eurodollars were the dominant setting. The real world got a close look at what it was doing first with the dot-com bubble and then the mania of the coincident housing bubble. Overseas, the eurodollar system was financing the EM “miracles” in what might fairly be called the third major bubble (the one yet to be fully reckoned with, though in some places like Brazil it has started to be).

By the middle 2000’s, monetary behavior was no longer as economists had come to expect and what they had encoded in their econometric models. In trying to reconcile the bond market with those models, Greenspan had his conundrum which Ben Bernanke put into the concept of a “global savings glut.” It was the final signal that economics, especially mainstream monetary economics, had lost all connection with actual, operative finance.

Because, however, his pedigree and credentials remain impeccable, his opinion still carries some weight; that is the world we live in, especially where the media is concerned. It doesn’t matter how much you failed, it matters where you went to school and what jobs you held while you failed. Appearing on BloombergTV yesterday Dr. Greenspan claimed yet again that the treasury bull market is over with, and once more demonstrating his confusion.

“Whenever you have a bull market, it looks as though it is never going to turn,” Greenspan, the second-longest serving Fed chairman, said in an interview on Bloomberg Television. “This is a classic case of a peak in a speculative security.”

I doubt there was any mention of his other such “calls” between his “conundrum” and now, including one just last year. Speaking at a private conference in DC in May 2015 before “global turmoil” erupted globally (it was only “overseas turmoil” at that time), Greenspan said:

Just remember we had the taper tantrum. And we are going to get another one.

He made that proclamation as interest rates were, in fact, rising. In late January, the 10-year UST yield had fallen all the way below 1.70%; but from that point through the spring interest rates had been increasing again as Janet Yellen’s “transitory” theme seemed to gain evidence. By the time Greenspan spoke of this next “tantrum”, the 10s had moved back up in yield to around 2.30%. Rather than continue toward 3.30% as he was suggesting, the benchmark bond yield would be nearly 1.30% by this July and proving yet again he is nothing more than an empty suit with a filled out resume.

It’s not just that he has been wrong about the direction of interest rates, it is why he has been wrong but more so because it perpetuates this same, very basic financial misunderstanding. In putting together the story on Greenspan’s BloombergTV appearance, the article’s authors clearly share the former Fed Chair’s muddled misunderstanding.

Investors globally have regarded monetary policy with growing skepticism that there’s more central banks can do to stoke inflation and economic growth. Asset-purchase programs and negative interest rates have pushed yields on more than $9 trillion of government securities worldwide below zero, according to Bloomberg Barclays index data. The European Central Bank triggered a global selloff this month after signaling it wouldn’t pursue further stimulus.

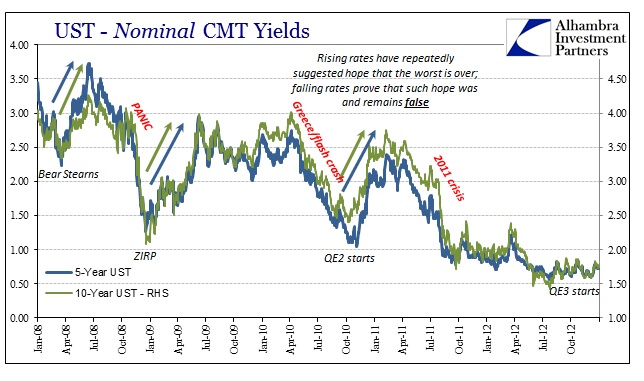

This is all demonstrably false and backward. The bond market hasn’t sold off because it is just now losing faith in central banks; bond rates have been falling for years as that market no longer has any faith in them whatsoever. The history of UST yields since 2007 is, pardon the pun, unyielding on this score. Bond rates rose in the aftermath of the panic because of ZIRP and all throughout QE1 as bond market participants didn’t understand what QE actually was. Believing it to be actual money printing, bond rates reflected both increased inflation and economic growth that were judged likely to result – only to stumble into shocking illiquidity in early 2010.

To that, the Fed responded with QE2 and the process started all over again. Treasury rates rose once more, not fell, while the Fed was purchasing UST’s – only to stumble all over again into even more shocking illiquidity in the middle of 2011 that finally registered as the realization of this eurodollar chasm between money and the actual role of bank reserves. Yet, despite all that, the bond market gave the Fed one more chance, though this time it was after QE3 and QE4, waiting to act in the same manner only when the Fed was willing to taper them. In other words, the bond market on the third try demanded some confirmation first that QE had worked before reflecting expectations of inflation and growth. The idea of taper itself was that confirmation; thus, the “tantrum” of 2013 wasn’t that the Fed was no longer buying bonds (at least as far as the treasury market was concerned) but that the bond market judged the success of QE at that point in time the most likely.

It didn’t last, of course, and ever since the bond market no longer has much faith in “stimulus”, harkening back to the questions about money and balance sheet expansion exposed by the 2011 crisis. Declining yields and a flattening curve leave no doubt as to the scenario that has been expected, one that has already been proved true. These periodic, almost regular selloffs that occur are not “growing skepticism” of global monetary policy, rather they are the brief and comparatively subdued flirtations with renewed faith that policy might achieve some results. And, as usual, those hopes are dashed in relatively quick fashion by reality.

Economists view everything in finance through the filter of monetary policy, and therefore attribute all results to that perspective no matter how illogical and strained. That is why their view of the world is so often upside down and/or backward. It is the legacy of the myth of the “maestro.” There is no reason, however, for that to have become and further remain the mainstream view propagated through the media. Greenspan’s credentials say nothing; his track record is all that should matter when judging the worth of his opinions. He doesn’t know what he is talking about and there is a mountain of evidence, including his own words, that show that he never did.

We are stuck in this economic depression not just because of his past tenure, but more so now because constant reverence prevents acceptance of these facts. The recovery doesn’t start until the “maestro’s” legend dies, and with it all the confusion and misconstruction about how markets and the economy actually work.