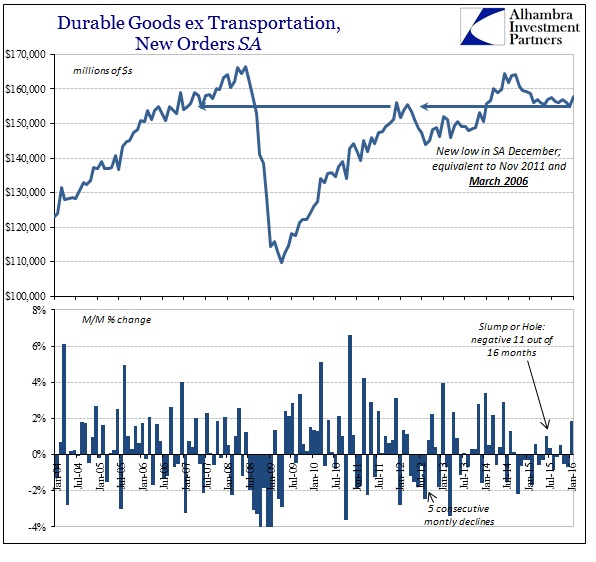

Anything with a positive number and the mainstream will jump. The latest was durable goods which only featured a positive number in the seasonally-adjusted series. Still, it was enough to send out the usual notices that the worst is over even for manufacturing.

The U.S. manufacturing sector could be on the mend after struggling for the past year with a strong dollar, weak global demand and plunging commodity prices.

New orders for durable goods—manufactured products designed to last at least three years—rose in January following their worst annual performance since the recession. That improvement, alongside a pickup in a key gauge of business investment, could signal the sector may be preparing to turn a corner.

The bounce in new orders, following two straight months of declines, mostly served to recoup some of those losses. But the rebound in Thursday’s Commerce Department report comes against a backdrop of other improvement in the domestic economy including steady job gains, a firming housing market and resilient consumer spending.

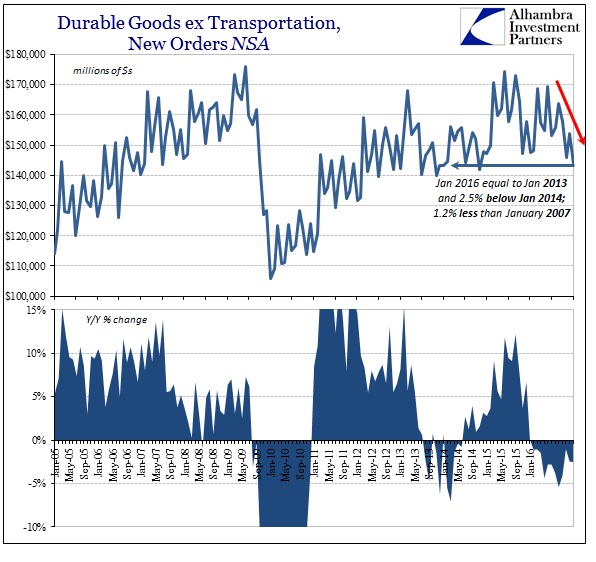

Maybe it’s the qualification “could” that saves the article from complete detachment, but actually examining the data (like “job gains” and that “resilient” consumer) leads to no such conclusion – not even close. The monthly increase in January in new orders was only in the adjusted set; in the unadjusted data there was no improvement to be found. Like retail sales, we are left to wonder how much was just calendar effects in the seasonal imputations. Even so, the adjusted estimate for January was still less than January 2015 along what is an alarmingly persistent trough (so far).

In the unadjusted data, the interpretations are much more serious. January’s estimate of $143.7 billion was slightly less than that of January 2013; it was 2.5% less than January 2014 and even 1.2% less than January 2007. There is nothing good to be said of any economic account that in 2016 can be unfavorably compared to the same month almost a decade and trillions in “stimulus” ago.

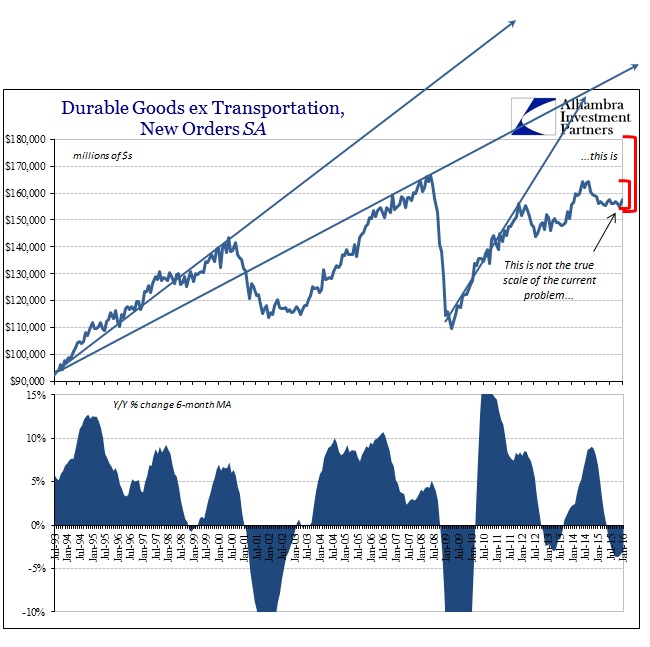

The “manufacturing recession” is a combination of current weakness piled upon past reductions even over the last few years where the economy was supposed to have been booming. To put it in perspective, durable goods orders (NSA) in January 2008 were 35% above the level of January 1999, and that was itself rather insufficient growth. By contrast, January 1999 durable goods orders were 35% more than January 1993. So to have January 2016 stuck below January 2007 is a huge indictment of any positive interpretation of the US economy.

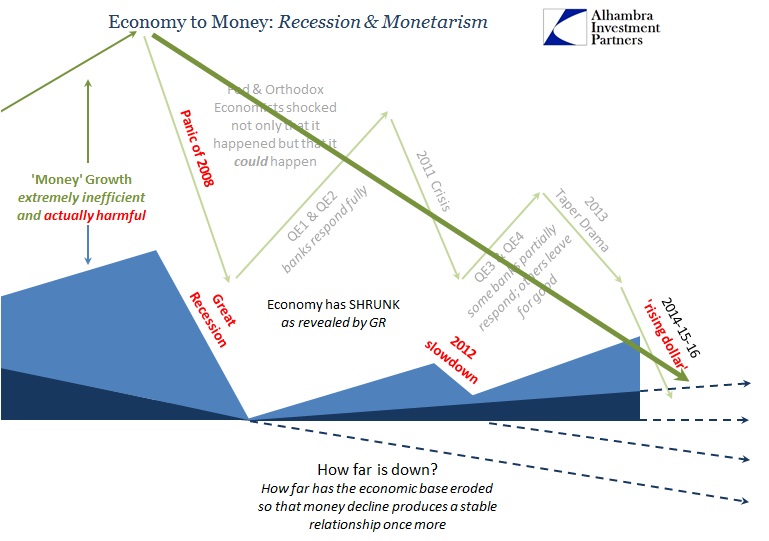

There is a huge difference between positive numbers and actual economic growth. This disparity over where the long run trend “should” be is enormous, and it is that trend that manufacturing businesses have counted on at least being partially restored in QE’s and “stimulus” as has been promised year after year after year since 2012. What’s important, then, in terms of recessionary consequences isn’t so much the magnitude of declines to this point (or the monthly positive variation) but rather the accumulation and persistence of them especially in relation to that (or whatever) expected long-term trajectory. In other words, the serious dropoff in activity in 2015 increasingly will convince businesses that the recovery baseline and narrative was never realistic.

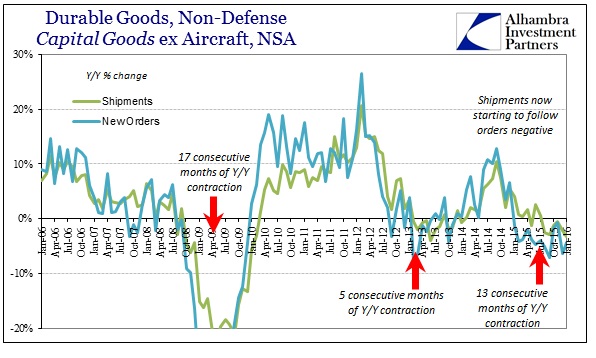

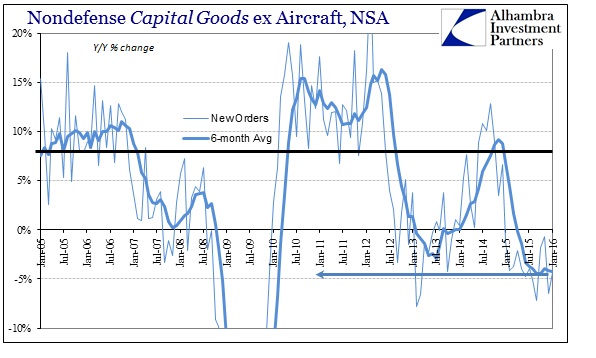

In the short run, again, added to this long term shrinking, there aren’t any positives, either. Durable goods orders (NSA) were down 2.5% in January (compared to the -0.6% in the SA series) while shipments dropped by 2.8%. That was the twelfth consecutive month of contraction in orders and the seventh in shipments (and eight of the past nine months). In capital goods, new orders were down 4.4% year-over-year, while shipments fell 3.3%. The 6-month average for capital goods shipments is now -2.1% which doesn’t sound like much, but is in fact the lowest of this “cycle” and equivalent to December 2008 (and April 2001).

The biggest economic enemy now continues to be time; consumers are not at all resilient, as these estimates for durable goods prove. After all, they have been contracting for a year or more based on those same consumers who have yet to experience really any of the typical recession pressures of large job losses and increasing reluctance among those fortunate to escape the adjustments. If consumers under relatively benign overall conditions can cause durable goods (and the rest of manufacturing) into a sustained, yearlong contraction, the economy has to be in much worse shape than even these numbers suggest. It is attrition now combining the long run, structural shrinkage revealed by the Great Recession with the short run weight of time.