We all have our own conceptions about money, as in many respects it is and should be deeply personal. Most people pay it little mind as all that matters is if our cars can be filled with gasoline and the local grocery store exchanges food for some ready and convenient method of payment. That used to be the primary focus of money and even monetary policy, as at one time the entire point of banking was on payment systems far more than finance (finance was a part of the system that enhanced economic ability).

Is there a proper distinction between using a debit card and using cash (currency) in the payment exchange? In the most relative and close terms, of course there isn’t in that both means allow the same ends. However, it all gets fuzzy the moment you peer behind the curtain and look at how each functions beyond the surface of just basic economic purpose; indeed, economic vitality is as much linked today to the financial “plumbing” as it is money as money.

It probably makes sense to define terms here, in that money ceased to exist in the United States at least by 1933 and in some ways even before then. Money, properly defined, is personal property subject to property laws. That puts the emphasis on ownership, and thus banks are merely bailees (with you as the bailor) entrusted with the safekeeping of chattel. The important distinction, and the crack into which all of this modernity in banking flowed, was that in the bailment of money banks were afforded the opportunity of fractionalizing claims.

At that point enters currency which functions as a means of a now-derivative claim on property. The governance of currency is entirely financial, a factor which seems tangential at best but is everything.

The main transformation from money to currency is that the power of money is local, whereas the power over currency is remote. In the 19th century, currency took the form of bank notes, which were exactly that – a liability of the bank as a promise to “pay” actual money upon conversion (the idea of convertibility in currency was literal and essential). This is not meant to be diatribe against fractional reserve lending nor a backdoor emotional appeal to the gold standard, only a summation of what I think are the important evolutionary aspects that led to the current wholesale system.

We still see these distinctions even in current practices today. If you deposit your gold bullion at a bullion bank you actually have a choice to make. They will offer you an allocated custodial account or an unallocated pooled account, with the latter being (often) much cheaper in terms of bank fees. However, the former is the primary relationship as described in actual money as you have made essentially a bailment with the bank. In the unallocated account, you are given not a direct claim on your gold as property but rather a liability of the bank which, if it were tradable, is essentially currency-like.

That again doesn’t seem like much until the bank fails. As custodian, the bank’s abilities and responsibilities are very clear – they cannot touch your gold for their own purposes, and must surrender it upon any attempt. In an unallocated gold account, your gold is gone as a liability pledged to the balance sheet structure of the bank. To see it returned to your possession is to navigate the financial laws of whatever jurisdiction.

This is not just a theoretical point, as it became fact in the bankruptcy of MF Global. There are, as you might expect, complications surrounding each individual relationship with the “bank”, but in the main there were expectations of a money-like relationship with MF Global as an agent trading commodities; physical possession rather than a liability of the bank. The fact of the futures trading format actually changes little about this arrangement.

But MF Global was a bank too, trading proprietarily alongside its activities as a custodial and trading agent for its clients. When all was said and done, the bankruptcy fled property jurisdiction under the CFTC and obtained SIPC standing as a fact of collateral in the bank liability structure (using other’s property as a means to obtain strictly bank funding); that meant what was believed to be more like bailment and property law was turned into a financial quagmire. The bank had thus claimed client “property” as its own liabilities, and financial law treated them exactly in that fashion (though most customers were returned their accounts, but it took a protracted legal and court process to get them).

So the great distinction in money vs. currency is really the emphasis placed upon the bank rather than the individual. In MF Global under property law, the bank doesn’t really much matter as its responsibilities are clearly defined to return all property in a timely fashion. In MF Global under financial law, everything is entangled in the bank’s own business and thus the bank is paramount over everything else.

This distinction gathers more than just bankruptcy, as it has taken on actual function; and it is there that the wholesale system became viable. Under a true gold standard, foreign trade is conducted mostly as a physical exchange of money – foreign partners contract with a London bank to physically move bullion from one account to the next. It gained more complexity when gold was required to move from London to New York or Paris, opening the door to the first gold derivatives in the form of swaps (where the Bank of England would instead of transferring gold in good London delivery form simply re-allocate some of its holdings at a corresponding central bank to their good delivery form), but the practical arrangement was the same – the bank’s role is custodial of simply accounting and safeguarding. If the bank holding gold fails, it is, again, of little practical importance as possession overrides.

The development of eurodollars muddied that arrangement exponentially. Under the Bretton Woods “gold standard”, foreign trade was conducted largely under convertibility of the dollar and pound. Again, trade was moved from property to finance, as even under that “gold exchange” standard what moved from account to account was not physical gold nor even physical currency but a notation on a ledger. Now, the account holder had the right to claim currency (physical dollars and pounds) and then even convert that into money (gold), a right denied Americans in 1933, but by and large it was a more remote financial arrangement of ledger “money.”

Such a framework holds massive advantages in terms of cost and efficiency. A ledger system is much easier to operate, in its simplest iterations, which is why eurodollars gained favor in the 1960’s (that and capital controls of the Kennedy and then Johnson administrations as they completely misunderstood what they called “Triffen’s Paradox”). By 1967, the Bretton Woods standard was essentially finished as even the Bank of England was engaging in dollar swaps to maintain its end of convertibility – leading in short order to a two-tiered gold price and then, in 1971, the end of convertibility entirely.

That meant for all practical purposes, there was no more money anywhere in the global system, as it had evolved into a creature of purely finance. To that end, the eurodollar standard that replaced it was again a ledger system rather than even a physical currency system. In terms of efficiency that meant ultimate pliability.

If under the gold standard foreign trade required the physical exchange of actual money, the eurodollar standard meant debt at the center of everything. If Brazil wanted petroleum from Saudi Arabia, instead of moving physical gold on account in London to an account of Saudi Arabia, a bank operating in the eurodollar market would lend “dollars” to Brazil and present a ledger balance to Saudi Arabia. However, the greater distinction still is that the transaction is, as it would be under physical and property domain, no longer self-extinguishing. Just as the eurodollar bank presents a positive balance, denominated in dollars, to Saudi Arabia, it will be offset by a credit balance to Brazil that must be, at some point, repaid or rolled; financed!

Thus banks are now at the center of global trade in what is really a debt standard. But whose liabilities are at the center of these ledger creatures? That is where I take the world from a dollar to a “dollar.”

Rather than viewing the evolution of eurodollars chronologically and trying to find the Patient Zero of the eurodollar market, something that even contemporary observers struggled mightily with as the eurodollar market “somehow” exploded into the 1970’s, it may make better sense to use a recent example.

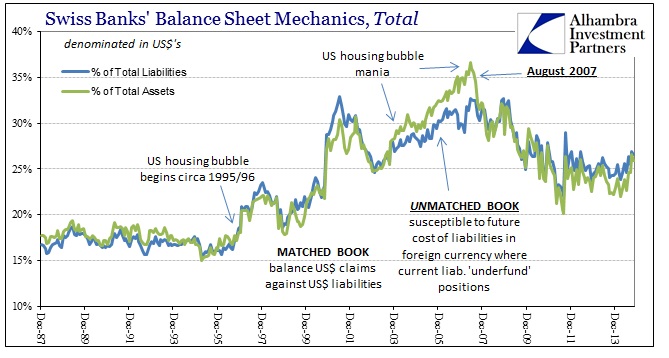

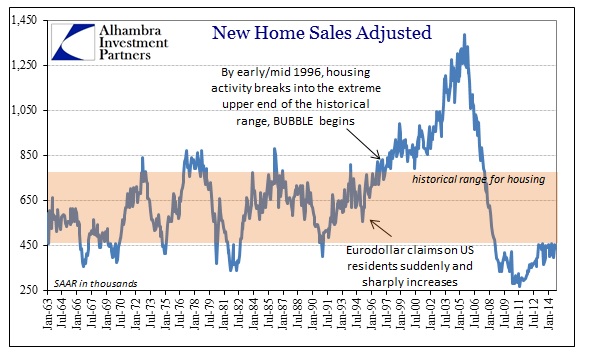

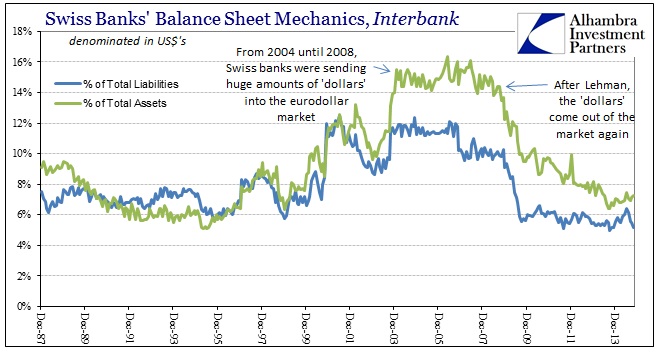

The housing bubble (and the dot-com bubble) are easily visible in the mechanics of the Swiss banking system, a fact that should create a great deal of pause from all those who profess monetarism and its characteristics in more local understanding. In the mania phase of the US housing bubble, a great deal of “dollars” were being supplied into the eurodollar market by Swiss banks. A very heavy proportion, quite possibly not just a majority but a large majority, of further financial institutions buying up the ultimate lending “products” of that bubble, the MBS tranches of various constructions, were also European in origin and operation.

So what we ended up with was Swiss banks supplying “dollar” liquidity so that European banks could create “short” “dollar” positions in order to finance a real estate imbalance of historically immense proportions inside a country on the other side of the Atlantic. What is a dollar in that arrangement?

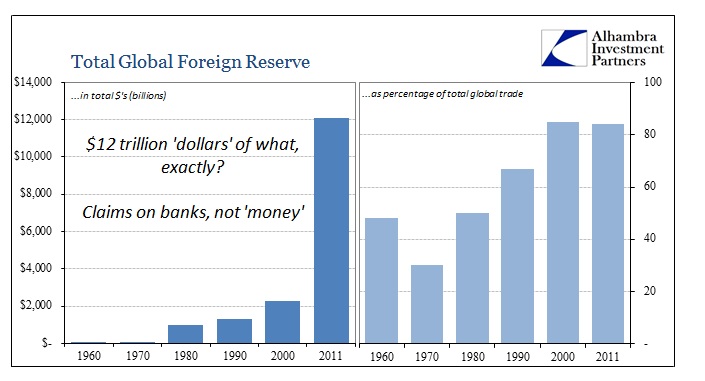

And that is the central point I try to make by referring to wholesale finance as “dollars” rather than dollars. The fact of the matter is that we have become so remote from money and finance as to not even be able to define it.

This is something that has been somehow ignored at the “highest” levels for some time. When the Federal Reserve stopped accumulating and publishing the M3 statistic, what it meant was the Fed no longer cared to even attempt a definition:

The discontinuation of M3 was met with conspiracy theory, that the Federal Reserve was engaged in a cover-up over the ballooning housing bubble, actively trying to suppress its own fingerprints in the over-financialization of the global economy. Since M3 tracked so much of the edges of the known financial world, there should have been a more determined effort to quantify and understand financial innovation of that period. The lack of such effort was taken as an implicit acceptance of bubblenomics.

In some ways it was that, but in more practical terms what it meant was that even M3 no longer conveyed a realistic assessment about what could fairly be called a “dollar.” These wholesale “dollars” exist as ledger creations of banks that may not have any relationship whatsoever to the Federal Reserve (supposedly the monetary steward) or even the United States. Indeed, under the eurodollar standard prior to 1985 most of those “dollars” in the form of debt were dedicated to trade exclusively among foreign partners – those trade “dollars” in that situation never touched the US or even US banking (this is not to say that US banks were absent, only that they weren’t and aren’t actually necessary).

However, they are made “real” in only one legal sense, that US banks are able to account for London eurodollar liabilities in their own operations (the bank holding structure). That created a form, and a weak one as we found out in August 2007, of legal acceptance of the eurodollars as dollars.

We know that the Fed was on to something about the difficulty in quantifying repos and eurodollars because we still have no idea today how much “money” appears out of nowhere due to repos and eurodollars. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) essentially corroborated that in one of its attempts at analyzing the 2008 crash in an October 2009 Working Paper, The US Dollar Shortage in Global Banking and the International Policy Response. Independently, the BIS was interested in figuring out how many eurodollars there were at the time to gauge what was essentially the “crowded trade” of the century (to date, anyway) – the shortage of US dollars in the eurodollar market created largely by European banks engaged in multi-national shadow banking.

The arrival and exponential growth of derivatives, especially, counterintuitively, interest rate swaps and eurodollar futures, are what allowed the proliferation of “dollar” liabilities to almost any form. The “Japanese housewife” of trading lore could fairly be added to some measure of “dollar” supply as they are notorious for buying US$ assets through Japanese banks and derivative “convertibility.” In other words, the “dollar” is Bigfoot.

When you appreciate and accept that the traditional idea of a dollar is long, long gone, you start to see the possibilities for financial complexity whereby the bank is at not just the center of it all, but in many respects all that matters – to the very high detriment to the real economy, as this lack of recovery has proved to anyone not blinded to anachronistic monetarism that still holds dear the easily disproved assumptions of monetary neutrality and closed systems. None of these would even be possible under a physical standard of actual money.

The downside of a “dollar” as a opposed to a dollar is that so much is now unobservable in the form of bank activities that never see the light of day (again, the bank at the center). Since we cannot even define a wholesale “dollar” we cannot think to even attempt its measure as it amounts to chasing a phantom. All that is left is secondhand (if you’re lucky, like 2007) or worse indications of what may be taking place somewhere. Worse than that, this is a dynamic system that is constantly re-allocated and re-adjusting in ways that cannot really be fully appreciated in anything even approaching realtime. And since a “dollar” can be almost any financial connection, that often means searching incessantly for the who, what and where.

The most frustrating aspect of the wholesale “dollar” is that there is a great deal of beauty and elegance in it. If operated as designed and intended (mostly) it would be a fantastic mode of modern convenience. But, like Milton Friedman’s eagerness to unleash floating currencies, the theory never matches reality. Bastardization of great ideas is more of a standard than an exception, and the “dollar” is certainly that. Like securitization and even gold swaps of old, these were good ideas that found serious financial favor, and like festering infections waited only for the right conditions to bring out the worst aspects in all of them.

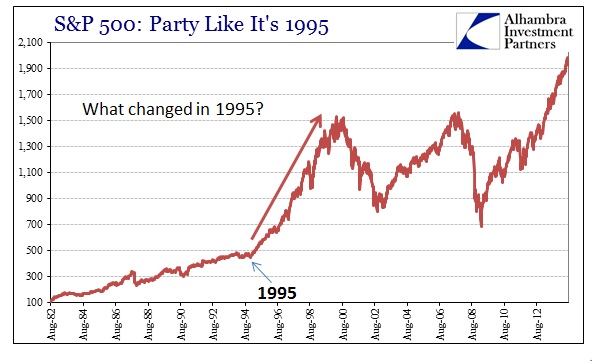

For the wholesale “dollar”, that was the 1980’s and really the 1990’s. Technology and regulatory changes, especially the move to interest rate targeting in the attempt at “filling in the troughs without shaving off the peaks”, unleashed the torrent. By the mid-2000’s, the entire global banking system had re-oriented to this fashion. We are left in the wake of that misguided bank-centric focus to simply appreciate as best we can what a “dollar” might be tomorrow; an opportunity perhaps to redefine toward more possessive, and thus individual-focused, constructs, or another curse to just watch where banks go with it all bubble after bubble.

That is the legacy and distinction of the “dollar.”