Some legitimate scientists are legitimately worried about the spread of information. The lack of boundaries afforded by an open internet has left the world awash in it, and with no shortage of opinion. This is a good thing. However, there is a downside in that unfiltered and unrefined information as it can be used to mislead both the person wielding it and those that choose to be swayed by it.

There is certainly an immense amount of noise on the internet, and it is the job of any scientist in any field to be a trained engine of filtering. Science itself achieved a level of reverence, however, that isn’t wholly healthy. It has become a barrier which is exposed the more it becomes closed off. Thus, the information available in the internet age can be a check upon the immutable fact that scientists, while deserving respect, are still human and thus should be comfortable with some level of public skepticism.

Some accept this proposition more so than others:

What does the evolving frontier of knowledge mean for society’s relationship with science? Long borders are difficult to patrol. Professional gatekeepers of scientific knowledge can no longer control the flow of information as they used to. In an age of the “University of Google,” people no longer rely on established, peer-reviewed literature but rather seek out manifold sources on the Internet. Fragments of scientific knowledge get absorbed into society this way, as do some scientific values and thinking—which by itself is good. But many of these fragmented bits of knowledge are also invalidated, politicized, and of dubious quality.

This self-driven accumulation of “knowledge” has created a healthy dose of skepticism among the public toward facts and arguments, as well as a more intense public engagement. Some speak of the modern citizen as a “proto-scientist,” emulating, no doubt incompletely, some of the well-established practices of academia. It is no longer enough for experts to argue by means of what mathematicians fondly call “proof by intimidation.” The authority of science has been eroded by these public debates, a subject that deserves a separate discussion. One of the immediate consequences is that the scientific community will have to spend much more time engaging with policy makers and the public, not only communicating the products of research, but also the scientific method itself.

This applies to all scientific disciplines including the so-called hard sciences, but more so to others like economics. The idea of “peer review” rather than act as an arbiter of “good science” has become a barrier to it. It has closed off the discussion into an echo chamber of only one set of ideas. Perusing any mainstream economic journal, one must marvel at the inanity and uniformity of the content. Those inside the bubble find themselves arguing triviality as if they were important debates of huge consequence – such as the “right” size of “stimulus” rather than whether “stimulus” is actually stimulative of anything other than the number of words (and regressions) printed in these journals.

Skepticism, then, is not due to the public’s unprofessional approach, rather it is invited because of economics’ closed circuit. The very fact that you are reading this right now is testament to that, as is the very reason that I write it. As noted last week, I never held any intention to become a serious student of how the Census Bureau actually makes its estimates for durable goods, but I have been forced to by the mainstream that refuses any summons to address the narrative shortfall that approaches a decade in length.

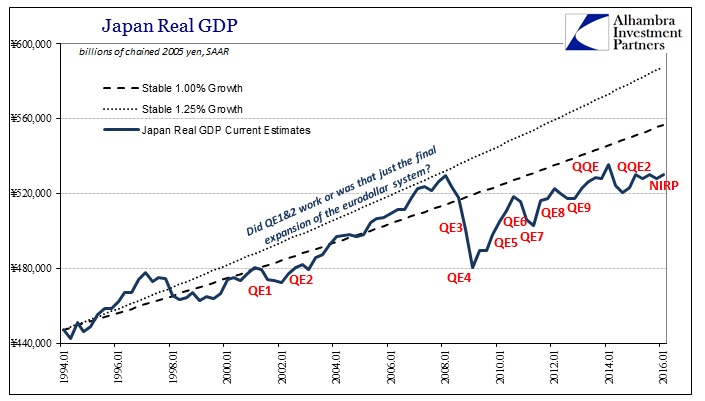

As is so often the case, Japanese officials provided this week the perfect example. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced that the scheduled tax hike would, in fact, be delayed by two and a half years. Everyone knew that this was coming; and everyone really knows why. But rather than admit to established observation as any devotee of true science would, the government of Japan ran through the most absurd little charade in a last ditch hope that the rest of the developed world would spark an opportunity to save Abenomics from the embarrassment.

We live in a world where the established class of economists tell us repeatedly that everything is good and grand but then for “some” reason cannot actually act as if it were; blaming instead some mysterious and unexplained “global turmoil” that prevents them from fulfilling their proclamations. They claim that any such weakness here in the US is due to “overseas” problems, when in fact US imports have declined right alongside US exports and all at the same time.

Economists and policymakers also fail to note, ever, that right now all those foreign economists and officials are blaming their problems also on “overseas.” As Prime Minister Abe said this week, “Faced with global risks, we must fully reignite the engine of Abenomics and speed up efforts to escape deflation.” It’s like trying to trace gossip back to its source; everyone who has heard it always hears it from someone else. Abe may try to ignore it, but even in Japan there is a great deal of skepticism as to that intention; why after three years of QQE is inflation still at zero and less?

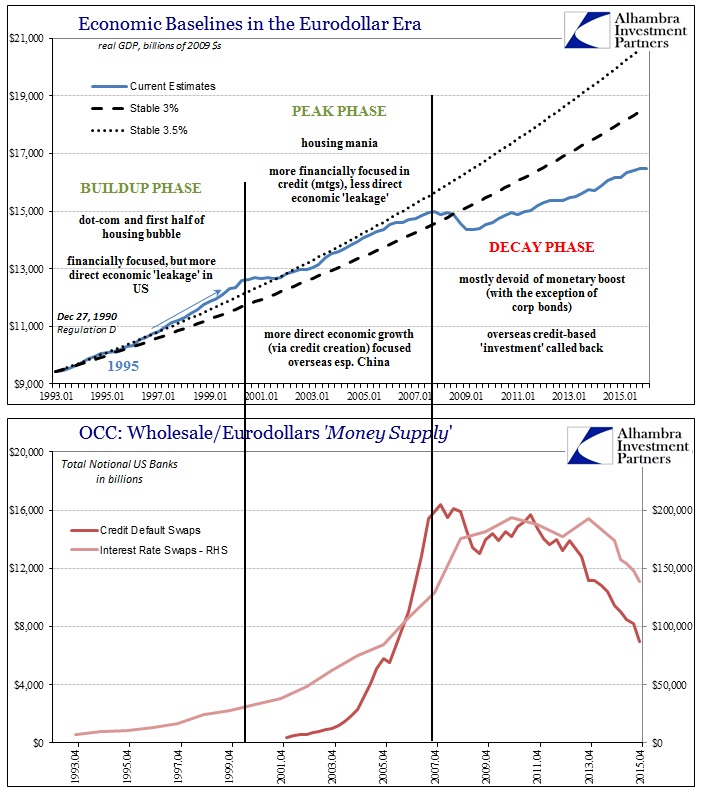

That was always the greatest danger of QE in all its forms and places. The “Greenspan put” functioned in trading lore only so long as it was never actually tested; it worked as myth but failed spectacularly in practice as early as April 2000. Essentially, global markets have been afraid of central banks actually being able to do what they said they could do. Up to August 9, 2007, that was never a problem (outside the dot-com crash in stocks) because there was no serious challenge. After that date, however, there has been no potency no matter the source or quantity of the “money printing.” In other words, economist policymakers were invited with some varying degrees of desperation to prove themselves and their assumed power.

It was something like madness of the crowd, where one person simply assumed that some positive benefit was attributed to monetary policy and it wasn’t long before everyone just assumed the same thing; nobody bothered to check. Not long after that, or maybe even before it (rational expectations theory, after all), central bankers themselves began to believe their own magic and influence, as if the mere shifting of whatever hand Alan Greenspan held his briefcase was actually significant. It was functional superstition and nothing more. They faced that reality in June 2003, but only for the briefest of moments.

Alan Greenspan’s warning at that meeting could easily be distilled as “make sure you can actually do what you say you can do before you actually have to do it.” Unfortunately, that would require honest assessment, which is something the Fed has demonstrated itself (over and over) never quite capable of producing.

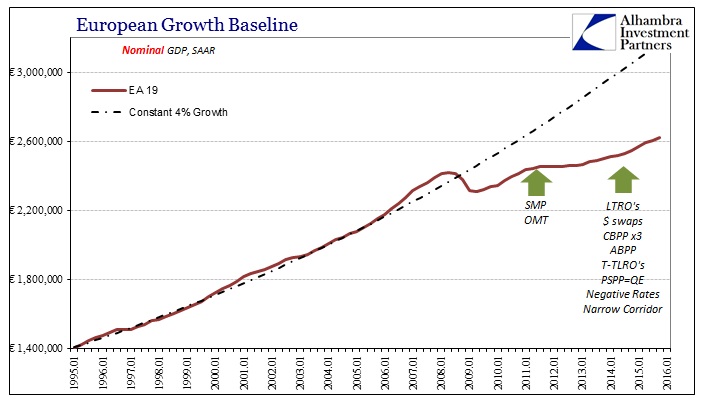

And so that was the task starting in August 2007; to prove that they could do what they said they could because leaving it as superstition was no longer operable. It was time to put up or shut up. They charged in believing in themselves and their magic, but rather than making the myth real they instead revealed to the whole world that the emperor not only had no clothes but that the guy walking around naked claiming to be the emperor was just some guy; and a crazy dude at that. Abe, the Bank of Japan, Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi, etc., etc., have proven themselves incapable of fulfilling their own promises by established empirical fact. They react not as scientists, however, seeking to first define and understand their failure but continue on as if they are still the fully-clothed regal monetary leader decked out in the world’s finest quantitatively-determined sartorial splendor.

Peer review and orthodox credentials are the palace guard of their pseudo-science, but the moat and the castle for it all is the media. The grand, expensive failure of the grandest myth ever invented isn’t even a topic for discussion. They still write it up as a recovery even as it withers under the slightest scrutiny; they won’t even report on the withering. It is the greatest story never told, how the world’s economy shrunk and all the monetary policy “power” in the world could do absolutely nothing about it – let alone start to investigate how and why the economy shrunk in the first place. Instead, as the day draws closer to the next possible RHINO (rate hike in name only) we’ll be flooded with endless stories of “full employment”, “the labor market is improving”, and “we have to act before inflation heats up” even though it has been four years since this all-powerful money printing agency last hit its inflation target despite trillions in additional “money printing.”

The downside of QE is the only practical effect; it proved central bankers as the frauds they always were. The trappings of institutional government were the same thing as Bernie Madoff’s accounting system. So long as the eurodollar system kept expanding the economy kept growing and the myth would perpetuate especially as Greenspan et alia kept acting like they were steering the whole time. Know eurodollar, know economy; no eurodollar, no economy.

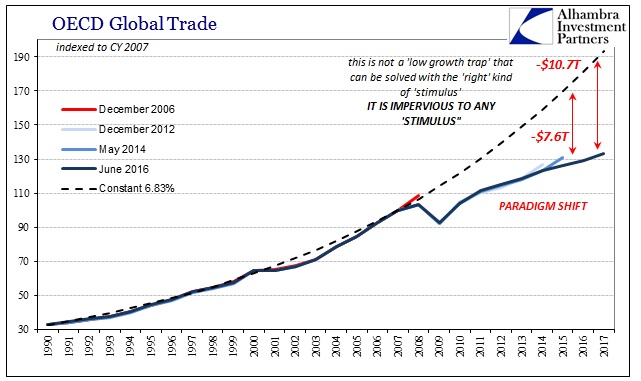

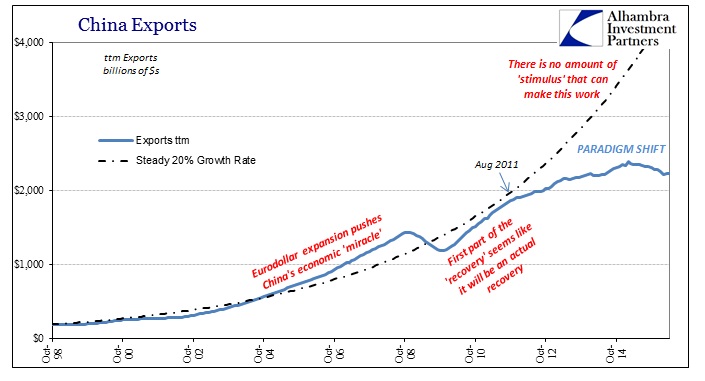

Maybe the illusion is “more real” to economists because the real economy only draws further and further from health and function; a kind of material delusion of disbelief. The costs in lost opportunity are now literally unimaginable. As noted yesterday, you cannot conceive of $10 trillion in “missing” global trade; the best you can do is understand how much disruption and turmoil such a calculation would easily explain. The people are skeptical of economics because economists have given them every reason to be. We can no longer live in their naked world of implied central bank ability; we now have to contend with an economy where the lie is the only revealed truth that matters. It’s a decidedly ugly place no matter how many times Abe, Yellen, Draghi, and the rest remark of its beauty and majesty. The more they do so, the more democratized, hopefully, this “science” of economics will become. Skepticism should always be welcome, but in these times it is truly indispensable.

The barbarians are not pounding at the gates of economic science; the barbarians are those already inside them. It is the knock of civilization and knowledge that now pushes their considerable defenses. We can only hope that the siege will not go on much longer, before $10 trillion in lost (forever) economy turns to $15 trillion and then $20 trillion. There is a very different world waiting for us at -$20 trillion, a projection that -$10 trillion already establishes.

Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence, and the evidence is nothing short of extraordinary: