In its 84th Annual Report released last June, the Bank for International Settlements departed from usual central bankish conventions and decried the growing departure from market discipline and even reality. The BIS even used the loaded term “euphoric” to describe what it saw as risk market prices no longer affected by fundamental economic conditions. As the Financial Times noted then,

The BIS, the bank for central banks, has been a longstanding sceptic about the benefits of ultra-stimulative monetary and fiscal policies and its latest intervention reflects mounting concern that the rebound in capital markets and real estate is built on fragile foundations.

That does seem to be the case as credit and funding markets in “dollars” are bearing out over time. Dating back to November 2013, these more basic markets are as disenthralled with the monetary state of affairs as the BIS. That leaves the question as to who, exactly, is so “euphoric?” Typically, bubble thoughts uncover biases against the standard idea of “dumb money.” It is believed to be the retail herd that causes both the bubble and its dastardly end. It is difficult to disprove that alone, especially recognizing the overabundance most recently of retail trading and imbalance there:

A broad look at the 6.5 million customer accounts at TD Ameritrade indicates that retail investors are “pretty fully invested” in stocks, the online brokerage’s CEO said Thursday.

Fred Tomczyk cited several signs of this: margin loans at high levels, client cash at low levels and account holders at the firm logging in frequently.

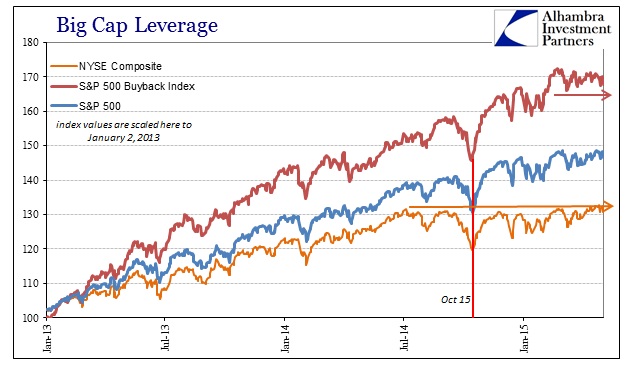

While Mr. Tomczyk indicated that such behavior was “a good indication”, recent history isn’t as charitable. Even if we set aside any doubts about dumb money/retail, it surely isn’t the case that that was where the stock imbalance was built. Retail investors really did not reengage until around QE3, and their influence is somewhat detectable in the straight-line advance throughout 2013 and the first months of 2014. But even there, it is clear that another powerful force was at work, and thus indicates that the premise of euphoria is institutional after all.

U.S. companies announced $141 billion of new stock buyback programs last month, the highest level ever for new buyback programs during a single month and an increase of 121% from April 2014, according to a count by Birinyi Associates Inc.

The rise now puts 2015 on pace to reach $1.2 trillion worth of announced buyback programs, shattering the 2007 record of $863 billion in authorized buybacks, Birinyi said Thursday.

The difference in performance between the top share repurchasers and the rest of the “market” is so drastic that it largely answers the BIS’s formulation almost perfectly. If the pattern of share buybacks wasn’t enough of its own in that regard, repeat the words one point two trillion worth of announced buyback programs aloud, and then realize that is just for the calendar year of 2015. There is no precedence anymore, just as there is no real way to grasp such immensity intuitively.

The basis for that rationality is always given as corporations (and their CFO’s) identifying undervalued shares on behalf of their shareholders. Circumstances in now two cycles totally dismiss that as nothing but urban, Wall Street legend. Companies always purchase far more shares when values are high, especially at cycle peaks, and almost no shares when they are (or were, as in 2009) obscenely low. The basis for this massive herd of buybacks is not valuation but debt.

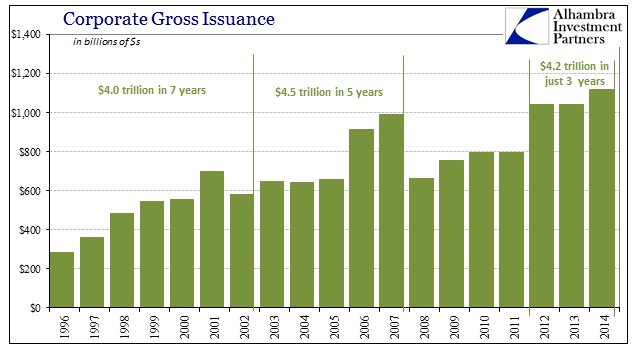

If we are to identify the bubble more properly, it belongs in that category almost exclusively. The increasing fortitude of corporate debt markets may be cast in a growing economy, but again circumstances dictate a far different interpretation. The trends in corporate issuance, which isn’t always a perfect proxy for total debt carried, argue rather decisively in the Fed’s direction, just as the BIS charged.

More corporate debt has been floated, according to SIFMA, in the past three years than in the seven years between 1996 and 2002. The past three also resemble quite well the last two full years of the last debt cycle, which coincidentally was the last time share repurchases were so ungodly imbalanced.

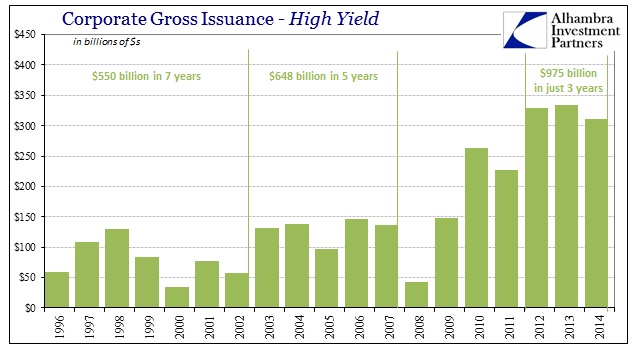

But the full extent of this corporate bubble isn’t revealed under the bland “corporate” category alone, it is in the worst forms for it.

There was $550 billion, total gross, in junk bonds floated in the seven years between 1996 and 2002; almost $650 billion in the five years immediately thereafter, coincident to the housing bubble. In the past three years alone, junk bond grosses have been just under $1 trillion! Jeremy Stein noted all the way back in early 2013 that QE’s and “reach for yield” might themselves coincide, but there is little doubt about that now. Perhaps that is why even Janet Yellen has seemingly swung back toward financial sanity despite growing economic worries.

The problem of the junk sector (which does not above, unfortunately, include the tally of leveraged loans; syndicated interbank “products” of equally dubious parameters that remain largely on the insides of the banking system and its institutional clients) is wholly different, in terms of economic insufficiency, than investment grade debt. Whereas investment grade debt is flowing into the stock market via repurchases, at the almost direct expense of capital expenditures, junk flows in two pathologies; one of stocks, the other of opportunity costs.

The former is in M&A’s and LBO’s, a rather modern, fiat currency invention that is most emblematic of the changing nature of finance and its now-domination on the marginal economic structure. Just yesterday, two marginal, struggling denizens of the semiconductor space announced their intentions to combine: Avago will “buy” Broadcom for $17 billion in “cash consideration” and $20 billion in stock, around 140 million shares at today’s inflated price. The Wall Street Journal, in looking at the transaction, describes the buyout target as:

Growth has been hard to come by for Broadcom, a 24-year-old company that makes communications chips for tablets and smartphones, and supplies the Internet links for cable-television and telecommunications devices. It earned $1.41 billion last year but has struggled to lift sales. Its revenue was up just 1.5%, to $8.4 billion.

“It’s really economically difficult to be a small semiconductor maker now,” Broadcom Chief Executive Scott McGregor said earlier this year. “The larger companies are going to look for consolidation.”

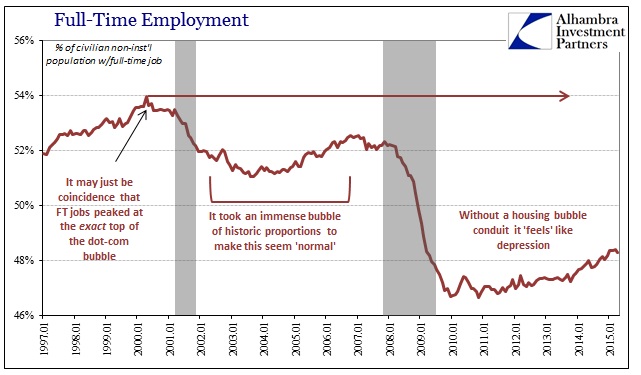

That is hardly a grand endorsement for great value, fortunately there is such a robust junk “market” acceptable for this kind of bailout. Under more true capitalist arrangements, the weaker firms failed outright, opening the door to smaller, more innovative challengers to rise up and reshape the industry – and even create new ones in the process. This financialism, which favors greatly the larger, more established firms, amounts to economic sclerosis. Most labor gains in our nation’s history up to the late 2000’s came from exactly these smaller firms that grew large, but in order for these gazelles to grow they need the space to do so. When given that, they bring their innovations to the forefront and cause all manner of beneficial disruption to the economic system.

That is healthy and sustainable economic growth where QE and its like are aimed directly at forestalling it and foregoing its benefits. The junk bond market and leveraged loans, more than anything, are now tools of economic decay because their abundance allows weaker and more inefficient firms to stumble on where gazelles could be bounding over their carcasses. All of monetary policy is dedicated to stasis, an artificial appeal of stability where true economic growth is marked by dynamic change and often rapid and disruptive evolution. The more monetarism holds everything in place, the less economy results.

Central Banks ca. 2008: We need financial recovery or we get no economic recovery.

Central Banks ca. 2015: We got financial recovery but no economic recovery. Economy is to blame.

The cumulative impact of a debt-or-nothing strategy is plain; only the discombobulations of regression equations prevents that from being recognized inside the small and getting smaller parameters of monetary theory. Monetary policy, especially at its greatest imbalances, strangles economic growth by placing emphasis on what amounts to great and detestable inertia. Artificial stability sounds nice until it lasts nearly a decade, or, frighteningly, even longer. If there is dumb money in that, it is only at the contours where resignation becomes the fullest expression of apathy, economic and otherwise. Central bankers talk about controlling and commanding “animal spirits” but they do no such thing at all; instead they strip animal spirits right out to the point that even the little guys, including in business, simply give up and just buy some stock. It’s so much easier after all especially since central bank “puts” take out all the risk.

The permeation of euphoria is in the institutional base, which is almost fitting in how all these measures have been arranged since 2007. It wasn’t, after all, the little people that panicked in 2008 it was the banking institutions, and only those that were full party to the wholesale system. Now that the wholesale system has been bailed out, they think, institutional rapture rekindles and the economy suffers for it. This is, by far, the most deleterious part of “too big to fail” as it transcends just specific financial firms or even a class of firms. It is, instead, a dangerous ideology that takes its full shot in denying any other way forward. None of this is capitalism no matter how much Milton Friedman’s name is invoked. It wasn’t in 1963 when he postulated really nothing more than a better central banking paradigm, and it surely isn’t now. At least in 1963 Friedman was talking about actual money and currency; the modern form of his “branch” is obsessed with nothing but debt and always more of it.