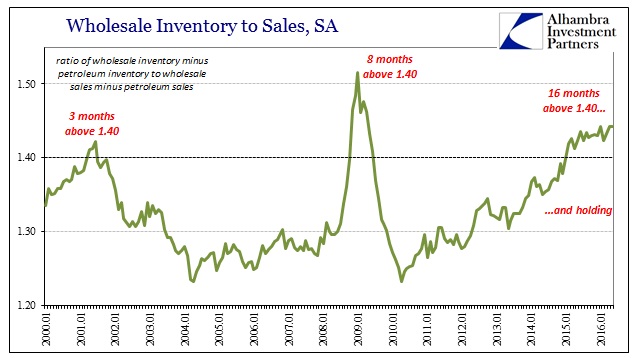

Wholesale inventories have ground to a halt, but since wholesale sales have also the inventory imbalance only continues midway already through its second year. Excluding petroleum, the wholesale inventory to sales ratio surged upward starting in November 2014. By the middle of last year, inventory growth had slowed but that only locked the current imbalance into seeming perpetuity. For the third time this year in May, the ratio was above 1.44 and comparable only to the Great Recession. The highest achieved during the dot-com recession was 1.422 in June 2001 because inventory declined sharply as sales did.

Similarly, though the ratio topped out much higher, during the Great Recession the inventory imbalance (a ratio 1.40 or above) only lasted eight months starting November 2008. Dating back to early 2015, the inventory-to-sales ratio (again, non-petroleum) has been above 1.40 in each of the past sixteen months; already twice as long as 2008 and 2009 with no end yet in sight.

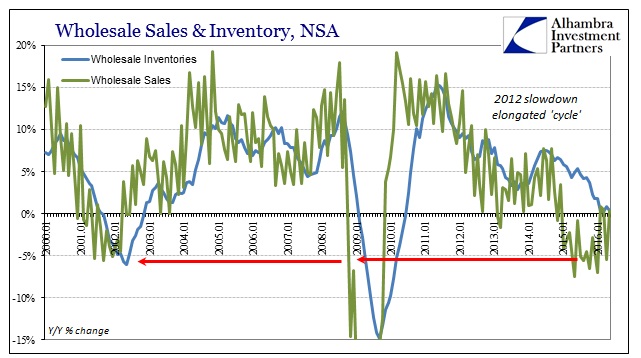

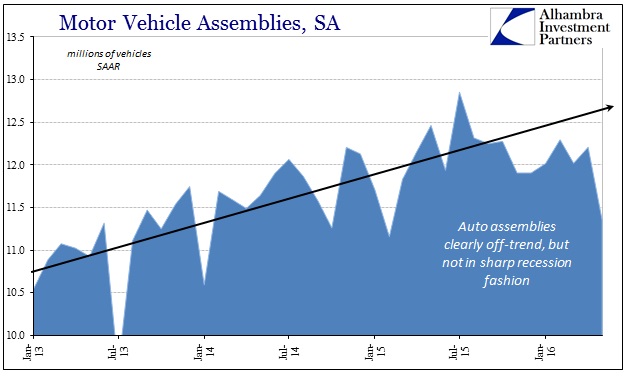

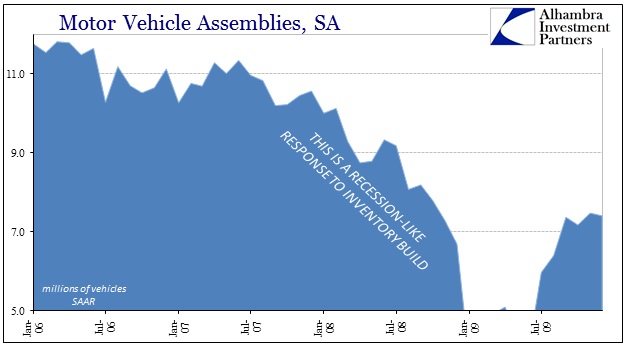

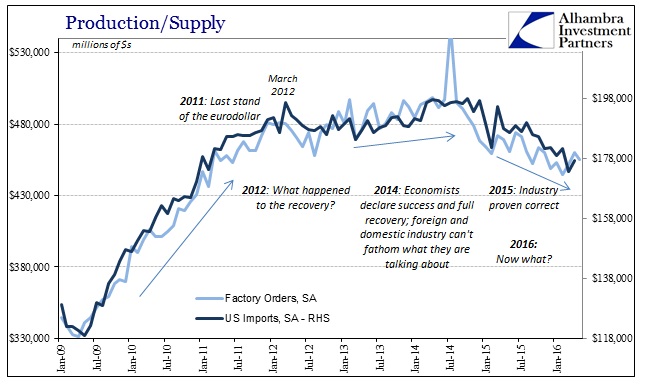

From this single data point we can appreciate both the occurrence of the “manufacturing recession” here and overseas and also its shallower slope. Production levels are undoubtedly responding to the buildup of inventory, but are not reacting in recessionary fashion meaning all at once. In both 2001 and 2008, responses to inventory were direct and immediate; the typical “V” of the recession portion of the business cycle. In 2014, by contrast, the buildup was somewhat less alarming in nature even if similar in ultimate level and scope. Further, businesses were constantly reassured that any such weakness at that time was “transitory”, making it more difficult to separate signal from noise.

In the nearly two years since, the economy has only further slowed rather than having experienced a direct, full-blown recession. As noted in many other places with so many other accounts, this is unprecedented and does not conform to the typical business cycle pattern. That may account for the more gentle reduction in production and manufacturing, general confusion really, though that comes with a greater cost in terms of time. In other words, a typical recession would very likely have been done and over with by now, with the US and global economy already well into a recovery (even if once more stunted). Instead, the global economy is stuck in a mild contractionary phase that nobody seems to know what to do about or even how to interpret.

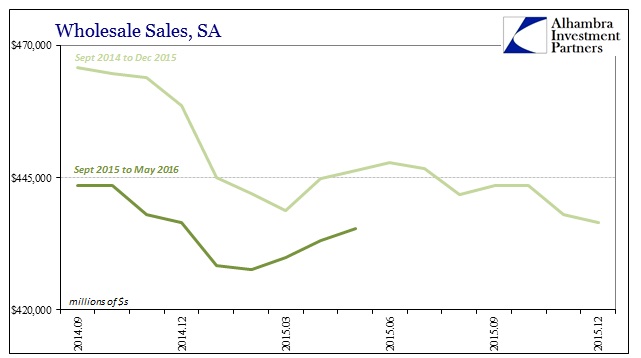

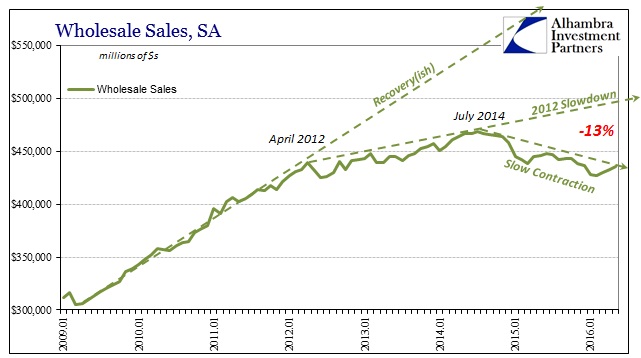

The topline environment shows at best stagnation and more often in the form of uneven contraction. Wholesale sales (including petroleum) were up in seasonally-adjusted terms in May 2016 for the third straight month but are 2.5% lower than May 2015 (wholesale sales were actually flat unadjusted). And wholesale sales in the spring of last year were also up for three straight months (April to June) before giving way to uneven contraction yet again. As discussed earlier, even in seasonally-adjusted figures wholesale sales exhibit this repeating monetary seasonality (with oil playing a prominent role in it).

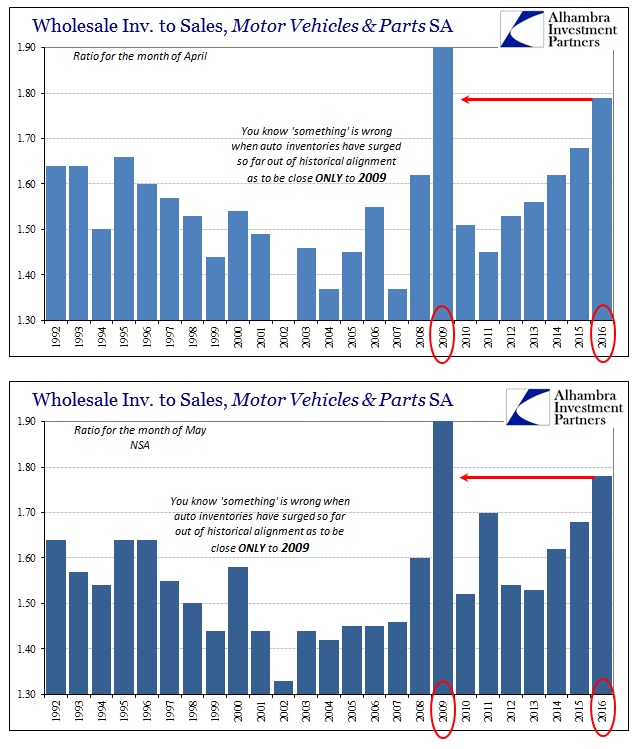

Because it is not the typical business cycle, production adjustments aren’t being made in typical cyclical fashion. Even in autos, wholesale inventories have risen precipitously to compare only to the worst parts of 2009, yet on the production side there has been no sharp curtailment in assemblies or overall production. We find (in other data such as industrial production) only continued probing lower as if fine-tuning for stagnation rather than growth. It is, again, a very unwelcome scenario far worse than any single recession.

Because the manufacturing economy remains stuck in this stagnation/contraction state, it is difficult to figure what comes next. By reasonable count of the inventory imbalance, despite almost two years of mild declines already there are still recessionary pressures that will have to be cleared up at some point. Unfortunately, we also can’t rule out a disastrous continuation of this zombie-like state of “growth.” All we can reasonably conclude is that the “rising dollar” period pushed the US and global economy into an even lower state from an already low state – smaller and slower still. Slow and steady growth has become slow and steady contraction, though to this point only on the sales side.

These statistics also understate the degree of economic pain already undertaken. Though wholesale sales are up for three straight months, they remain in the downward trend at a pace nothing like what would be necessary to rebuild economic strength. By simple arithmetic, wholesale sales in May 2016 “should” be somewhere close to $500 billion just to keep pace with the slow and steady baseline of the 2012-2014 slowdown period; let alone the +$600 billion in sales that would have been consistent with actual recovery(ish) from the Great Recession. At just $435 billion, sales in May were an enormous 13% off even the lower 2012 trend (and more than a quarter less than the weak recovery trend from before 2012). That is the compounding of lost time, the hidden but highly destructive cost of what might be by the end much, much worse than recession especially spread across two years or more of overall if uneven contraction – all following a further two years before that of unusual and suspiciously slow growth.

Because it hasn’t been recession, economists and policymakers have no idea what to make of it. They continue to act as if the economy is growing if deviating “temporarily” due to “anomalous” weakness (like snow) even as these aberrations have become routine. But, as is clear from this wide context, weakness is no anomaly at all, it just isn’t and hasn’t been recession; it’s much worse than that. While those that propose “secular stagnation” basically assign blame to an economy that somehow forgot how to grow, the answers are much more basic, simple and uniformly indicated across all these production and sales figures. Everything points back to 2011 and the “dollar.”

Because there is no fix even being considered for the eurodollar system, it seems quite reasonable to assume that the economy will only continue in this state – even if we have no idea what that really means. All we can suggest is that it will be skewed negative (maybe highly and even cyclically so) and nothing like the euphoria created by the intermittent payroll reports that have for years looked nothing like this rest of the economy.