By Paul Hannon at The Wall Street Journal

As various central banks loosened monetary policy this year, some economists predicted another cycle of beggar-thy-neighbor currency wars, in which countries race each other to become the cheapest exporter.

But it hasn’t panned out that way, and now a growing body of evidence suggests why: A shift in trade dynamics is blunting the impact of a weak local currency.

This could be all the more relevant now, when the monetary policies of the world’s most powerful central banks—the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank—are heading in very divergent directions, possibly taking the value of their currencies along with them.

When a country loosens its monetary policy, interest rates fall and investors tend to pull their money out in search of higher yields elsewhere, pushing down the currency’s value.

That is still happening. But the dynamic isn’t affecting trade flows as much as expected. What has changed is where businesses source the things they need to make the products they export. Manufacturers once found most components needed to make their goods at home. Now they increasingly look abroad for such inputs. As a result, exports now incorporate a lot more imports.

It is still the case that when a currency such as the euro weakens, it reduces the price of goods sold by German manufacturers in the U.S. But it also increases the price of the things that German manufacturers import to make those exported goods.

Measuring the impact of global supply chains on trade flows is the task of a project undertaken by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Trade Organization.

Using detailed figures from economies around the world, economists at the two bodies have measured how much foreign content there is in each nation’s exports, confirming a significant increase since the mid-1990s. The foreign content of Switzerland’s exports, for instance, increased to 21.7% in 2011 from 17.5% in 1995, while the imported content of South Korea’s exports almost doubled, to 41.6% in 2011 from 22.3% in 1995.

Economists at the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have used those measures to assess whether currency movements have the same impact they once did on exports and imports. They found that the effect has in fact reduced over time, by as much as 30% in some countries.

Policy makers are beginning to take note. “As countries become more vertically integrated via global value chains, exchange-rate variations will have a diminishing impact on the terms of trade,” said Benoît Coeuré, a member of the European Central Bank’s executive board and one of its thought leaders, speaking in California last month. He concluded the process will reduce the role of currency moves as “shock absorbers” that direct global demand toward weaker economies from stronger ones.

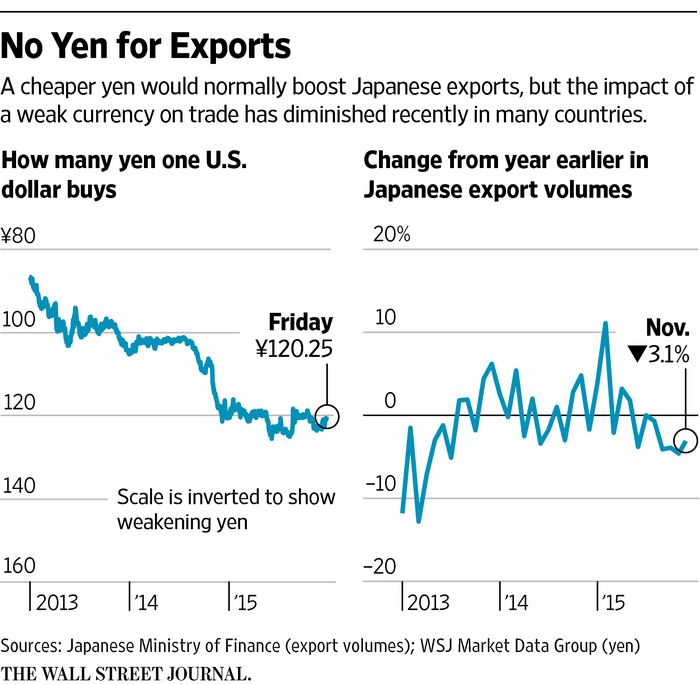

Japan offers the clearest indication that big currency depreciations don’t deliver the export boost they once did. In early 2013, the Bank of Japan launched a massive stimulus program that increased the supply of yen and led to the currency’s sharp depreciation against the dollar and the euro.

That strategy was a key element of Japan’s package of measures designed to lift the economy out of a long period of stagnant growth. But what followed was something of an anticlimax. The yen’s weakening had little impact on Japanese exports, and failed to restart economic growth. Puzzled policy makers pointed to the weak state of demand in the global economy, but even if that were the case, Japanese exporters should have gained market share.

A similar pattern has emerged in the wake of the ECB’s January decision to launch its own program of quantitative easing. Like the yen, the euro weakened, continuing a decline against the dollar that started in early 2014 and now amounts to roughly 20%.

In early 2015, the launch of QE was expected to boost eurozone growth by aiding exports. But once again, the impact of a weakened currency has been modest. Indeed, in the three months to September, eurozone growth was held back by a more rapid growth of imports over exports, while industrial output flatlined.

Experts believe it takes about 12 to 18 months for foreign-exchange moves to have their full impact on trade flows, so the effect would have been felt by now in both the eurozone and Japan. The euro started weakening against the dollar in early 2014, while Japan is about three years into its currency depreciation.

Those disappointments don’t mean currency movements caused by the great divergence between the Fed and the ECB won’t have any impact. That is a key concern for U.S. businesses in the wake of the Fed’s decision this month to raise interest rates for the first time in almost a decade—just weeks after the ECB moved its policy in the opposite direction. Many economists still expect the U.S. to suffer some slowdown in exports, while the eurozone enjoys some pickup. Already in the first 10 months of 2015, the U.S. trade deficit widened by 5.3% from a year earlier, reflecting a decline in exports.

And as the economists from the IMF and World bank have noted, the degree to which a currency movement boosts or reduces exports depends on how large their foreign content is. For the economy as a whole, the foreign share of U.S. exports is at the lower end of the global range, at around 15%, compared with more than 25% in Germany.

“It’s more complicated as a story for the U.S. because of the low foreign content,” said Sebastian Miroudot, a trade economist at the OECD.

Source: Why Weak Currencies Have a Smaller Effect on Exports – The Wall Street Journal