So much of the basis for monetary policy was put in place in the 1960’s study of the 1930’s. It has become commonplace simply to assume 21st century tactics as being directly lifted from the start of the Great Depression. One of the causes of that calamity was certainly restrictive money supply, but any dereliction on the part of the Federal Reserve under that condition should not be judged by the current paradigm.

Ben Bernanke has claimed that he “had” to act lest the panic in 2008 turned into something worse (it did anyway, so the mainstream imagines an even worse counterfactual to make it seem that monetary policy achieved at least something). In 1929 and really 1930, that wasn’t the Fed’s job. At the outset of the Great Depression, the Fed had only one job to do and that was currency elasticity. The economic implications of that task, or in that case not doing it well, were tacked on later. Economic management wasn’t something envisioned until 1935 under the reorganization of Marriner Eccles and really Lauchlin Currie.

Currie re-imagined a Federal Reserve System empowered to do much more than the mechanical; the typical god-complex that you see today in economists who task only themselves to save the world (and end up making it worse). In Currie’s case, it was almost explicit, as he advocated a private banking system backed by only government monopolized money. But it must not be forgotten that one of the primary reasons its supporters used to justify the Fed’s own existence in the first place was a very real and very large cyclical swing in the semi-annual money supply. Owing to the agrarian nature of the US economy even in the early 20th century, there were vast changes in money supply distribution as crops flowed one way and money the opposite.

It is a myth that the private banking system did not efficiently handle such direct monetary needs of seasonality. The problem was instead the natural bottlenecks of just these kinds of patterns and associations; which is why financial panics all seem to have occurred in the autumn, particularly October when money in the money centers was at its lowest ebb (as cash and gold flowed away from NYC to the interior). Conventional wisdom surrounding the Panic of 1907 was that the “people” no longer wished to be beholden to the ultra-rich like JP Morgan as any one of those natural bottlenecks was sure to trigger the next bank panic. Instead of the profit motive of a few on Wall Street, the Fed was inserted with its bureaucratic rigidity to really manage and safeguard not the predictable seasonal variation but rather the unpredictable (something bureaucracies are not well-known for).

We don’t see much of such heavy seasonality any more, partially because economists have worked in the decades since to erase it even in the smaller economic statistics. In other words, there is no longer an agrarian swing in money supply, but that doesn’t mean there is none in the economy. The Christmas shopping season remains an anchor on the monetary calendar, but one that is perhaps less defined as money moved from a tangible concept to its current wholesale incarnation.

And yet, especially in the past few years, there are more and more signs of seasonality and bottlenecks appearing all over again. The most contentious of recent times is the “residual seasonality” associated with Q1 GDP particularly of the past few years. Even adjusting its “seasonal” factors, the BEA has been unable to dismantle what is a clear pattern in the data; Q1’s have been noticeably and consistently weak. In the context of the Christmas shopping season, as each one has only become weaker in recent years under this slowdown economy, the overhang of especially a weak holiday trade environment only makes sense (if US consumers knock themselves out only to create a weak economic Christmas, it follows that the months thereafter would be especially weak).

It has led in the past three years to weakness at the ends with relatively better conditions in the middle. The uneven nature of the slowdown is undoubtedly related to this unappreciated seasonality; thinking in straight lines can only lead to trouble.

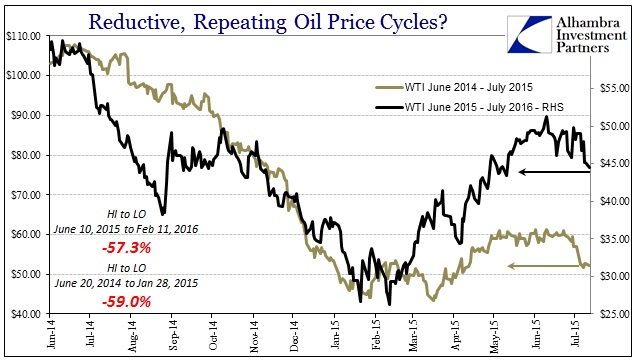

The same might said of financial markets and indications and what might be at heart monetary causation. Early last July, the world seemed to be in a much better place than when the year had begun. Though there were dark indications gathering underneath, economic stats seemed better as did market prices. In the first half of July 2015, the S&P 500 soared to as high as 2,128 buoyed in no small part to the oil rally that was “sure” to mean all weakness had been isolated only in the start of the year. Having dropped as low as $43 in March 2015, WTI had robustly retraced through spring to more than $60 per barrel. There were also new injections of “stimulus” (European QE) as well as further talk of more in other places (China, Japan).

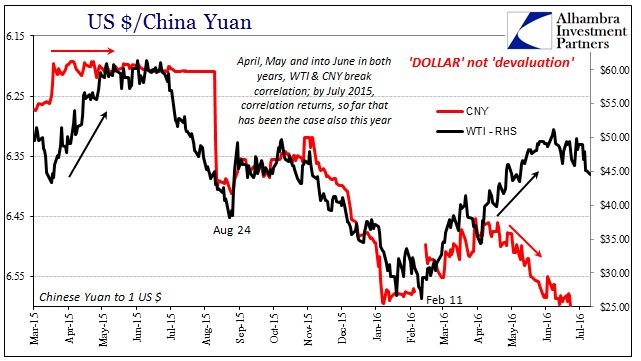

In many ways, that was a similar pattern to 2014; and it is so far shaping up again as the template for 2016. Though the S&P hit a new high today at almost 2,140, once again oil is already treading lower in seeming sympathy with outward “dollar” (read: CNY) irregularity. Oil prices likewise turned lower in late June 2015. Even today, where near-euphoria reigns in stocks, oil is conspicuously lower in direct sympathy with CNY.

At around 10:30 am ET, CNY moved sharply lower after having traded close to unchanged for the Asian session (positive for liquidity and risk). WTI futures (front month) at 9:30 am CT were at the day’s high near $45.80. As CNY broke lower from 6.689 to near 6.6975, WTI futures (front month) fell more than $1.25 despite the huge “risk on” sentiment everywhere else. Worse, most of that decline in the futures curve was contained at the front end – the tell-tale sign of negative “dollar” influence (a/o 3:35 CT, the front month contract was down $0.90 from yesterday’s close and $1.25 from the intraday high; the May 2017 contract, less than a year out, was down only $0.10 from yesterday’s close and $0.30 from the intraday high).

Since early June 2016, WTI is down almost 15%, with a majority of that decline being booked after June 29. The general direction seems locked in no matter the vacillating moods in other risk assets. It is, again, an eerie seasonality stretching now into its third consecutive midyear (When did oil prices peak in 2014? June 20, also up rather sharply from weakness that January). From CNY to repo to eurodollar futures, there were signs each year preceding each inflection that suggested building “tightness.”

In far too many places to be coincidence, we find the same all over again. Nominal treasury rates in spring 2015 that had been rising so much that the 10-year UST was talked about as if 3% was a foregone conclusion, suddenly turned sharply lower around June 26; falling from just under 2.50% to less than 2.00% by the August liquidations. The nominal 10s yield this year was about 1.85% on June 1, less than 1.60% two weeks later, and under 1.50% by the start of July. What is it about midyear that seems to bring, at least under the “rising dollar”, hardened seasonal “tightness”?

Each of the past three years have been defined in exactly the same general pattern, all cleaved in seeming anticipation of the calendar’s center.

Maybe it shouldn’t be surprising or even controversial. Since the economy has exhibited seasonal variation over and above statistical attempts to address it, it seems at least plausible to define it in monetary terms even to the point of causation. The agrarian base to the US economy has been erased by the evolution of technology, but on some level seasonality still clings to some vital parts of the whole operation. And we should not forget or discount the global nature of the “dollar”, meaning that any search for cause in repetition must not be entirely domestic. There is perhaps a much greater and wider global seasonality in the whole “dollar” than might be represented by only the visible geographic parts – all of which might be more easily bared by, to paraphrase Warren Buffet, the receding systemic tide of “dollar” liquidity.

In other words, seasonality has always been present just unnoticeable because monetary conditions were normal or at least sufficient until the more recent eurodollar breakdown; we should also not forget that the Great Recession itself followed just this same pattern, both 2007 and 2008. The Fed, true to its own version of mandates, rejects elasticity altogether as it only cares about economic management based in full part on misreading this unevenness, regular as it may be. Whatever might be at the center of this seasonality exposes the entire global system as being increasingly naked as “dollar” insufficiency becomes more the operative condition. It’s just that nobody seems to notice this regularity because the rising “liquidity” of each spring is mistaken for what everyone really wants. Midyear is here again and for the third year in a row it already indicates what everyone would rather not revisit, including stocks.