Near the start of her tenure, Janet Yellen in a speech given on April 16, 2014, at the Economic Club of New York declared monetary policy concerned with three big factors. The first was inflation and whether or not it was moving back to the 2% target, even though by then it had been almost two years since that was the case. The second was what are called “unforeseen headwinds.” Early in the recovery estimates for the track of labor improvement and normalization of monetary policy went hand-in-hand; as the former gained, the latter receded. That never happened, as the unemployment rate had to that point largely met expectations but normalization was only then being discussed years behind original forecasts.

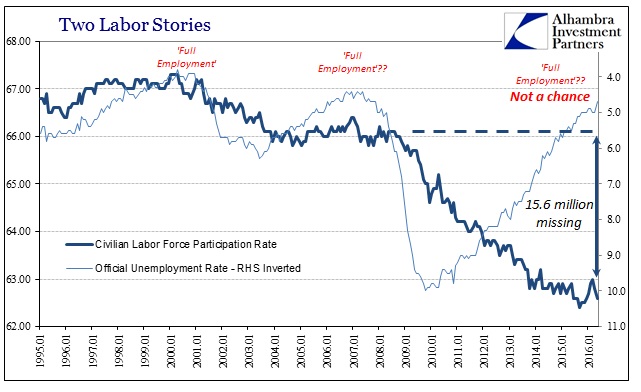

Yellen’s third factor was really her and the economy’s first – the labor market itself. She framed it under terms of “slack”, which the central bank uses to judge the appropriateness of any policy setting. Slack is the theoretical buffer between labor improvement and inflation, meaning that it is the very intersection between the Fed’s later two legal mandates (currency elasticity being its first task, having already failed badly at that, too). Because the Great Recession was so large and deep, it was expected that payroll normalization would take longer than usual. In April 2014, FOMC models predicted a further two years before “full employment.”

I will refer to the shortfall in employment relative to its mandate-consistent level as labor market slack, and there are a number of different indicators of this slack. Probably the best single indicator is the unemployment rate. At 6.7 percent, it is now slightly more than 1 percentage point above the 5.2 to 5.6 percent central tendency of the Committee’s projections for the longer-run normal unemployment rate. This shortfall remains significant, and in our baseline outlook, it will take more than two years to close.

Here the forecasts had it all wrong. It didn’t take two years to achieve the upper boundary of the central tendency, it only took ten months. To blast all the way through the lower boundary, and reach 5.1%, the “best jobs market in decades” needed just eighteen. With the unemployment rate far lower than they expected, policymakers had painted themselves into a corner where the most visible economic statistic in America suggested a much different economy than anyone outside the media actually experienced.

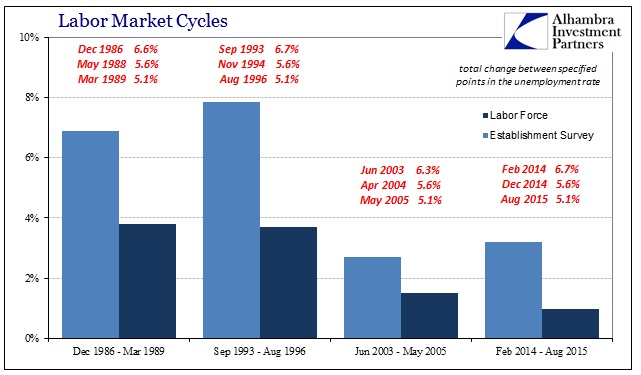

The manner in which the unemployment rate dropped, however, was entirely different than in any other similar appraisal. Between February 2014 and August 2015, the Establishment Survey showed a gain of 4.4 million jobs, a rate that was a statistical improvement upon the earlier “recovery” period (and sounds impressive in a vacuum) but nowhere near what was exhibited in past cycles at the same levels of official unemployment. Further, the labor force itself, the unemployment rate’s denominator, grew by just 1.5 million, with more than half of that total from January 2015 alone.

In percentage terms, the Establishment Survey registered a 3.2% increase while the labor force managed just 1.0%, which combined was enough to send the unemployment rate careening to “full employment” in about half the time the Fed’s models predicted. In the recovery after the 1990-91 recession, the unemployment rate needed 35 months to complete the same journey, only then the Establishment Survey increased at more than double the rate while the labor force jumped by nearly four times what was estimated for the current “cycle.”

The numbers are similar in the later 1980’s, as well. The only comparable “recovery” to the current run in the unemployment rate is, of course, the upswing after the dot-com bust. In these four cycles we see a vast difference in labor market conditions that show very well the unemployment rate’s flaws.

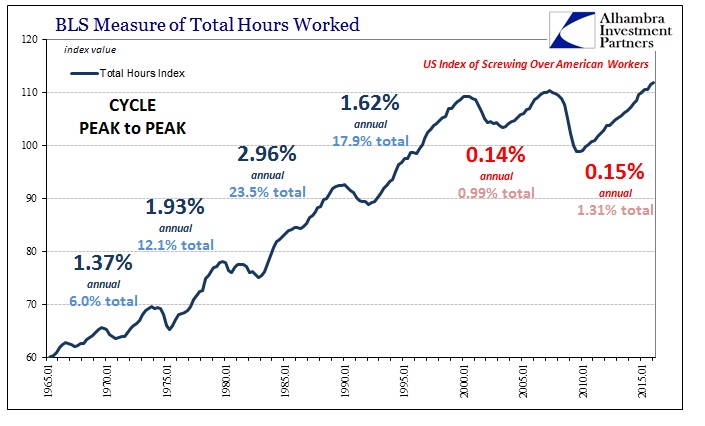

It is clear that the very idea of “full employment” as given by the unemployment rate has changed in the 2000’s to something far, far less than it once was. This result is perfectly consistent with other labor statistics, such as the BLS’s Index of Total Hours Worked.

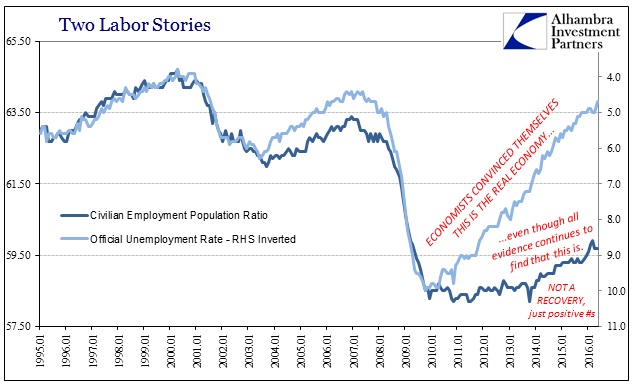

It is more confirmation that full employment only applies to the smaller subset of what the unemployment rate actually measures – not the full economy but the shriveled portion that still shows up in the official statistics. In raw terms, there is no comparison of the “best jobs market in decades” in 2014 and 2015, inferior in every single way and to a stunning degree, yet it is treated as if consistent with a healthy economy solely because it fits the preferred narrative. The real economy, however, cannot escape what is far more than a mathematical inequality.

This has left policymakers and economists in a tough position, to try to explain the participation problem in terms that don’t consider the economy radically reduced. In her Jackson Hole speech in August 2014, Janet Yellen laid out these factors first with those that appear benign:

As an accounting matter, the drop in the participation rate since 2008 can be attributed to increases in four factors: retirement, disability, school enrollment, and other reasons, including worker discouragement. Of these, greater worker discouragement is most directly the result of a weak labor market, so we could reasonably expect further increases in labor demand to pull a sizable share of discouraged workers back into the workforce.

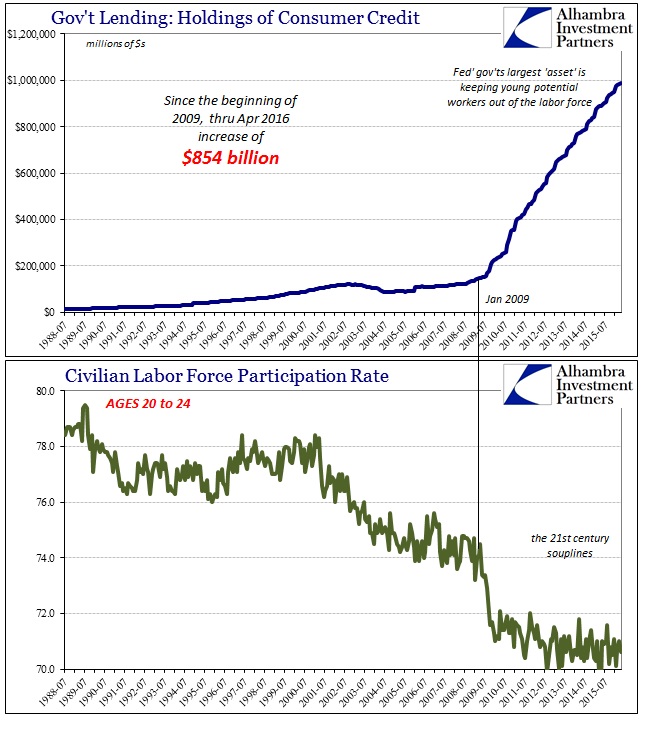

In reality, we know reasonably well that all of those are just as likely caused by this economy as natural, organic progression. The Great Recession’s aftermath was a great many nasty things, but neither a sharp, sudden rise in dangerous work environments or a palpable decline in worker health were among them. In other words, the disability excuse is in some good (full) part an economic factor, too – as is the lower participation rate among college-age adults, who clearly have been using the true fiscal “stimulus” of student debt to avoid having to face the contracted labor market.

So it is really no surprise to find economic weakness in the past two years over and above what has become criminally normal. At last July’s semi-annual Congressional testimony, Yellen explained that despite these obvious challenges they would not linger long largely because of what she saw in the unemployment rate:

Low oil prices and ongoing employment gains should continue to bolster consumer spending, financial conditions generally remain supportive of growth, and the highly accommodative monetary policies abroad should work to strengthen global growth.

There isn’t any part of that assessment that remains true, especially now that the labor market has fallen into question. Indeed, in her testimony before Congress yesterday and today, Yellen’s prepared remarks admit, “the pace of improvement in the labor market appears to have slowed more recently.” With no tinge of self-awareness, Yellen now instead claims the reverse:

The recent pickup in household spending, together with underlying conditions that are favorable for growth, lead me to be optimistic that we will see further improvements in the labor market and the economy more broadly over the next few years.

This shriveled, contracted economic base in labor utilization has left the Fed Chair once again to talk in circles. Last year, overall economic weakness was of little concern because of “ongoing employment gains.” This year, the slow labor market will pick up because of underlying economic conditions. So when the overall economy is weak it is the labor market that will see it through, and when the labor market is weak the overall economy will return the favor; as if these are concepts entirely divorced from each other.

That is the real point of the multi-cycle context and these shattering comparisons from different eras. If labor utilization has been so greatly reduced, and it certainly has been, we should expect to find an economy that only struggles no matter how the unemployment rate trends; while also a great deal of confusion among those that refer to the unemployment rate and slack as if they were the same as during the 20th century. Being unable to explain this discrepancy, Yellen and policymakers are left with retirement (which is refuted by the employment-population ratio of Americans over 54), disability, and college students as if the post-GR change in each were consistent with a healthy economy. Even the verdict of the unemployment is damning when viewed properly as true slack.