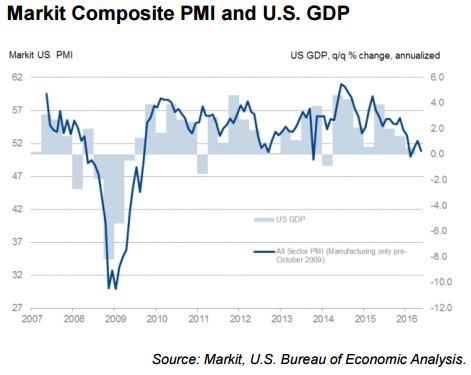

Markit’s Services PMI fell to just 51.2 in May, dropping a rather large 1.6 points from 52.8 in April. That meant the combined US Composite PMI, which puts together both manufacturing and services, was barely above 50, registering just 50.8. As with all PMI’s the distinction around 50 is unimportant, what matters is the direction and for more than a single month. On that count, services reflect what we have seen in manufacturing: that the “rebound” in March and April was nothing more than a small relative improvement after the liquidation-driven start to the year. The economy didn’t get better, it for a few months just failed to get worse.

In terms of the Services survey, Markit reports several distressing indications including respondents’ views for the immediate future:

May data highlighted a renewed fall in business optimism across the service economy. Reflecting this, the balance of service sector firms forecasting a rise in business activity over the year-ahead eased to its lowest since the survey began in October 2009. Anecdotal evidence suggested that uncertainty related to the presidential election and concerns about the general economic outlook had continued to weigh on business confidence. [emphasis added]

While I don’t want to overemphasize individual parts of individual sentiment surveys, it is quite a contrasting summation with the apparent self-delivered economic approval of the FOMC to execute the next policy communication (rate hike in name only). And this is not manufacturing, it is the services component that is supposed to steer the economy far away from the “manufacturing recession.” That was always a dubious proposition, particularly when so much of the supposed “services economy” itself relates to the transportation, management, and then sale of goods.

On that count, Markit’s Chief Economist Chris Williamson noted that May’s update reflected very poorly on measurement expectations for Q2:

Service sector growth has slowed in May to one of the weakest rates seen since 2009, and manufacturing is already in its steepest downturn since the recession.

Having correctly forewarned of the near-stalling of the economy in the first quarter, the surveys are now pointing to just 0.7% annualised GDP growth in the second quarter, notwithstanding any sudden change in June.

This is all a dramatic change condensed tellingly into a rather short economic window. The manufacturing sector has been shrinking for almost two years, but in the service sector indications (such as these PMI’s) had only pointed to a slowing from 2014’s supposedly upbeat pace. Even just six months ago, in the flash Markit US Services PMI for November, the mood was entirely different:

Looking ahead, service sector companies were upbeat overall about their prospects for growth over the next 12 months. However, the degree of positive sentiment remained subdued in comparison to the post-crisis average. Some panel members noted that signs of weaker global economic conditions were a factor leading to caution about the outlook for business activity at their units.

Williamson added:

The US economy is showing further robust economic growth in the fourth quarter, with the pace of expansion picking up in November.

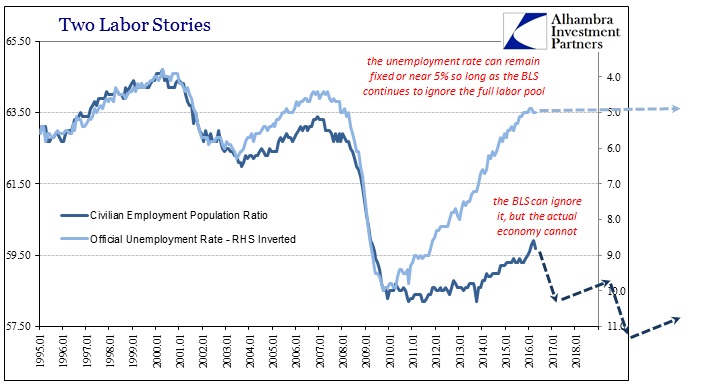

Again, it’s another indication that “something” changed toward the end of last year. In November 2015, service businesses were suggesting only “signs of weaker global economic conditions” but now in May 2016 that has been transformed into “concerns about the general economic outlook” such that forward economic optimism is like 2009 and nothing at all like what is in Janet Yellen’s world. We don’t have to wonder why that would be, as even the FOMC has provided all the necessary indications about “global turmoil” as shorthand for the “dollar.”

Even from a purely psychological standpoint, two successive, massive global financial disruptions (which weren’t really about the stock market, though it shows you just how deep they were that they would so interrupt the third equity bubble this century) both of which were declared “impossible” would wear down a wide margin of those still waiting on Yellen’s recovery to occur. That has been the story throughout the slowdown back to 2012, as markets and economic agents alike have given the orthodoxy wide berth to continue to claim “it is coming” even though evidence for that view remained powerfully scarce. The belief may have been more emotional than rational (even “recession fatigue” after the Great Recession had seemed to linger in the air for year after year) as people beaten down by continued disappointment will latch onto even the most fantastical hope. That was QE3.

What was left of the “recovery”, then, was little more than that faith. Once the plausibility of the happy ending was sufficiently challenged, there was little left to offer actual economic support. The successive “dollar” events of the past year certainly erased a good deal of that plausibility; the first one in August was just enough to entertain doubts no matter how many times Yellen said the words “transitory” and “unemployment rate”, and then the bigger one in January clinched them. I think that is why we have seen this shift in apparent economic condition and outlook, and why it happened when it did.

When Citigroup’s economics team proposed in December that the “outlook for the global economy next year is darkening” I wrote that it represented, apologies to Winston Churchill, the end of the beginning. It was a starkly different view from what they had forecast the prior December (2014) or even in individual statements made by members of the team just months before.

What has changed since? For one, Citi seems to have sensed that the Fed’s role is only to make matters worse, thus their citation of yield curve inversion. More than that, the “manufacturing recession”, for whatever proportion of the economy it might directly effect, has become real not just in more indisputable fact but more so in what it suggests about the direction of the economy, services and all. Citigroup may still be lagging financial indications, especially the “dollar”, that were suggesting this fate long ago and projecting it into commodity and fixed income markets, but at least they appear to be approaching it with a refreshing accountability to something other than Yellen’s models and “next year’s” certainty.

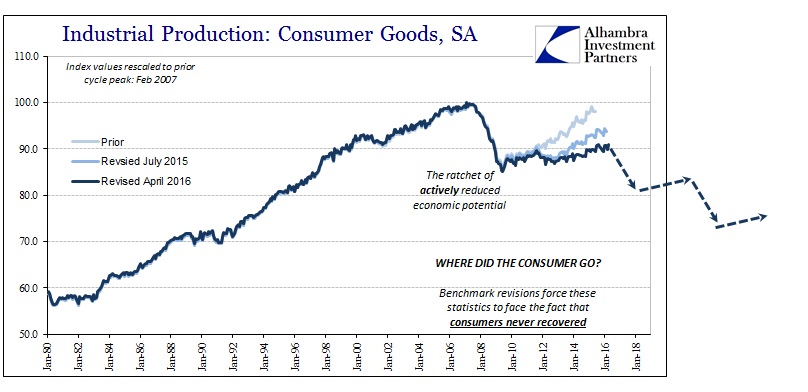

Five months later, having gone through the second liquidation with no traction of a real economic rebound from it, phase shift does appear to be the growing prognosis. Whether or not that adds up to the historically conforming recession cycle isn’t clear, and may not truly matter in the end. As noted here, the more important factor is whether any recession would be a true cycle or just another ratchet down toward further and lengthy abyss. The PMI’s of late are in agreement that the slowdown is moving past the “manufacturing recession” phase to whatever it is that might await the economy next.