Janet Yellen is a chatterbox of numbers, but most of them are “noise”. And that’s her term.

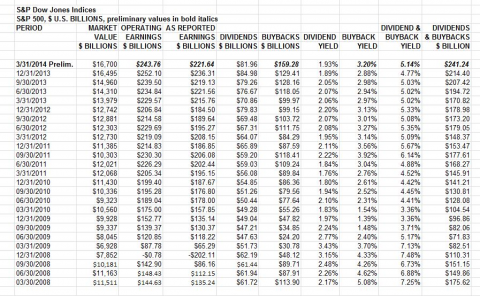

Yet here is a profoundly important set of numbers that you haven’t heard boo about from Yellen and her mad money printers. To wit, during the “difficult” economic times since the financial crisis began gathering force in Q1 2008, the S&P 500 companies have distributed $3.8 trillion in stock buybacks and dividends out of just $4 trillion in cumulative net income. That’s right, 95 cents of every dollar they earned—including the huge gains from restructurings, downsizings and job terminations—was flushed right back into the Wall Street casino.

Self-evidently, the corporate form of business organization is designed such that some considerable portion of net earnings should be returned to their owners each year. But a 95% rate of distribution is a giant aberration. Were this outcome to occur on the undisturbed free market, for example, it would signal an economy that is dead in the water and that participating companies face a dearth of opportunities to reinvest profits in future growth.

Needless to say, that is the opposite of the “growth” and “escape velocity” story that currently excites stock market punters, and is wildly inconsistent with present capitalization rates in the stock market. That is, in a world of permanent zero growth and nearly 100% earnings distribution, the S&P 500’s current 19X PE on reported earnings would be wildly too high. The more appropriate PE would be in high single digits.

So the $3.8 trillion of dividends and buybacks since Q1 2008 reflects not the natural economics of the market at work, but the artificial regime of monetary central planning and the tax-advantaged treatment of corporate debt. Corporations are eating their seed corn because boards and CEO’s function in a Fed-created financial casino where they are massively incentivized to feed the fast money beast with ever larger share buyback programs in order to shrink the float and goose per share earnings. Doing so generates plump stock option gains, and failure to do so will bring on the black plague of shareholder “activists” agitating for big stock buybacks with borrowed money, and a new CEO and board, too.

Moreover, this pattern is owing to the fact that the Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen “put” under the stock indices has destroyed two-way markets and the natural short interest that arises in any honest securities market. Accordingly, “downside insurance” against a decline in the broad market has become dirt cheap—as currently reflected in rock bottom VIX levels—-and has therefore enabled Wall Street gamblers to chase momentum plays at will. Stated differently, the momentum chasing hedge funds which drive the corporate buyback mania would not be nearly as profitable—-or massively sized—- if the Fed were not effectively subsidizing their downside hedges.

By now this syndrome has become so completely entrenched that the big cap corporate universe functions as an integral component of the Fed’s serial bubble finance cycle. As shown below, the pattern is wildly pro-cyclical, meaning that corporate cash increasingly fuels the bubble as stock prices reach their peak. Just prior to the financial crisis in Q1 2008, for example, share buybacks and dividends among the S&P 500 companies amounted to 130% of net income—-a distribution rate which plunged to just 65% during the dark days of Q1 2009.

But now we are off the races once again. The distribution rate reached 88% in CY 2013 and came in at nearly 110% in Q1 2014. In short, as financial markets reach their Fed induced bubble peaks, companies spend all they earn and all they can borrow chasing their stock prices ever higher. Indeed, during the most recent quarters, share repurchase programs have been the marginal bid which has propelled the stock indices to their current nosebleed heights.

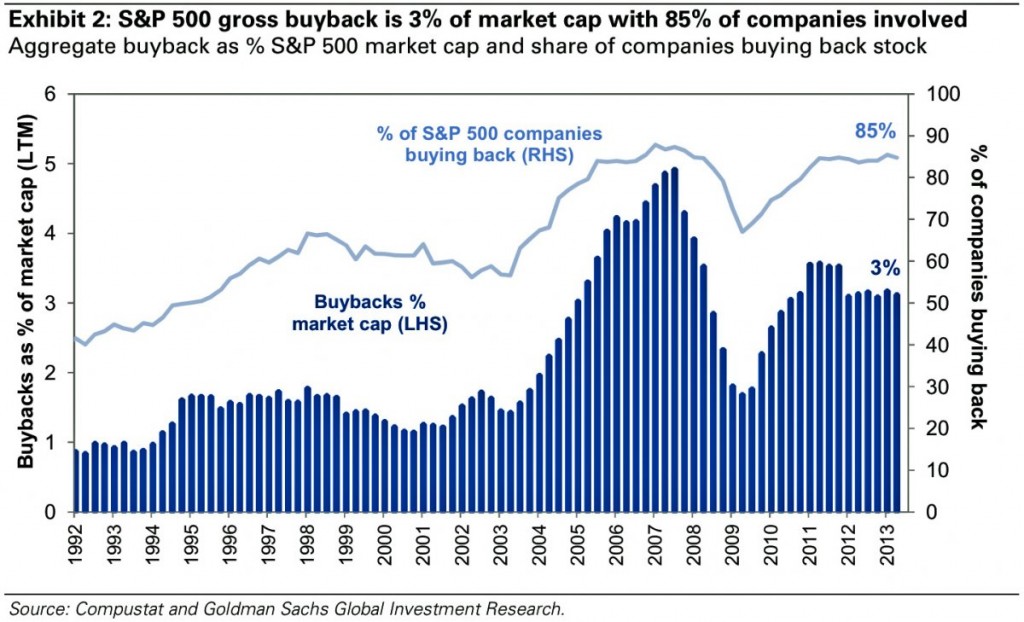

Corporate stock buybacks thus function as a bubble cycle accelerator, meaning that they are making each new Fed reflation cycle more extreme and unstable. Prior to Greenspan’s irrational exuberance moment in December 1996 share buybacks amounted to about 1% of the S&P 500’s aggregate market cap. By the 2007 peak, they exceeded 5% and are heading in that direction once again—this time accompanied by a rising rate of regular dividend payouts, as well (not shown).

It does not take much analysis to see that this kind of financial engineering results in the inflation of existing financial assets, not the creation of new productive capacity. The graph below on net investment in fixed business assets is the smoking gun. The annual nominal level of net investment has not increased since 1997, meaning that after about 2% average annual inflation—real investment in new capacity in the US economy has shrunk by nearly 30% in the 16 years since the first Greenspan bubble began its final ascent. Stated differently, as the Fed’s money printing has ballooned and amplified the financial bubble cycles, the trend in real capacity growth has steadily worsened.

Needless to say, no Fed minutes ever even hint at the corporate seed corn that is being consumed or the perverse behavior in the C suites that has been induced by monetary central planning. Instead, its all about the “noise” emanating from the high frequency in-coming data.

Also unremarked is the fact that the share buyback mania leaves competitively challenged businesses in a precarious position and unable to weather downturns in the general business cycle or in their own sector. Radio Shack is a prime example. It is now tottering on the edge of bankruptcy, and there is no doubt whatsoever that this is owing to a giant strategic error by its management and board. To wit, during the past 13 years it repurchased $3 billion of stock on the back of only $2.1 billion in cumulative net income. Indeed, in seven of those years it flushed back into the market more than 100% of its earnings—including $400 million of buybacks in 2010 on only $200 million of net income.

Today it is in a liquidity crisis, with barely $60 million of available cash. The article below fills in the grisly details about how this case of corporate hara-kiri unfolded. But the essential point is that it is not a unique case—just a leading edge illustration of the manner in which the Fed’s destruction of honest financial markets is impairing and gutting the nation’s business economy.

By Eric Englund

“The omnipresence of uncertainty introduces the ever-present possibility of error in human action. The actor may find, after he has completed his action, that the means have been inappropriate to the attainment of his end.” ~ Murray N. Rothbard

RadioShack is in the business headlines again; and not in a good way. For instance: “RadioShack’s weak first quarter results underscore the material challenges in its core business segments with few options left to stem the declines given a tightening liquidity situation, according to Fitch Ratings.” The same day, June, 11, 2014, a Wall Street analyst fretted about how quickly RadioShack is burning through cash. This analyst went on to assert RadioShack had a greater than 50% chance of filing for bankruptcy and, accordingly, his target price for RadioShack’s shares is $0—which isn’t far off of the present per-share price of 97 cents. So how did RadioShack, which had been a stock-buyback machine from 2000 to 2011, manage to eviscerate shareholder value so thoroughly that its stock has declined by nearly 99% from its December 6, 1999 high of $78.50 per share? RadioShack’s directors and officers, to answer this question, gutted the company through a reckless stock-buyback program that burned through cash as if it was trash. With the ongoing share-repurchase mania, other companies will likely follow RadioShack into insolvency.

Wall Street’s conventional wisdom contends that stock buybacks enhance shareholder value by “investing” excess cash in company shares, through share repurchases, thus improving earnings per share which should translate to higher share prices. Here are some basics:

► Earnings are split amongst fewer outstanding shares; resulting in higher earnings per share

► Excess cash, which is a low-yielding asset, may be better used to repurchase shares if management does not see opportunities to grow the business through capital investments on property, plant, and equipment

► Extra cash can be directed to shareholders without raising a company’s dividend

► Management is signaling to the market that the company’s stock is undervalued so it is investing in its own business

What you will not hear from Wall Street shills is that stock buybacks do have negative financial consequences. Let’s say a publicly-traded company, with $10 billion of cash, announces it will deploy “excess cash” to repurchase $5 billion of its common stock over the course of a year. This company, undoubtedly, will capture the uncritical and fawning attention of the talking heads on CNBC and Bloomberg TV. If the CEO of this hypothetical company grants a TV interview, I rather doubt he will have to answer any of the following questions:

► What will be the benefit of weakening your company’s balance sheet by reducing its cash, working capital, and equity positions by $5 billion?

► How does a weaker balance sheet enhance shareholder value?

► What is “excess cash”? How do you know when you have too much?

► In a world of uncertainty, how does management have the ability to accurately foresee the company’s future cash needs?

► Would it make sense to possess a cash war chest should management, in the future, see capital investment opportunities which would lead to greater profitability for the company?

► After completing the stock repurchase do you intend to re-issue shares, at a profit, should your company’s shares attain a higher price after the buyback?

► Does this buyback program have anything to do with financial engineering to help boost executive compensation to the detriment of the company’s financial strength?

Such an interview would be great fun to watch. Sure this CEO would gloss over such questions and then would pontificate as to why this share-repurchase program will be wonderful for shareholders. Yet the truth of the matter is stock buybacks generally are not effective at enhancing shareholder value. Moreover, after a buyback is completed, shares typically are not re-issued at a meaningful level to replenish cash.

In RadioShack’s latest quarterly report, management implies the company’s financial woes are attributable to the losses experienced over the past two fiscal-years; with losses continuing into the current fiscal-year. Here is what management stated in the latest 10-Q:

We have experienced losses for the past two years that continued into the first quarter of fiscal 2015, primarily attributed to a prolonged downturn in our business, which continues to impact our overall liquidity. In response to our liquidity needs and to continue execution of our strategic turnaround plan, we entered into the 2018 Credit Agreement in December 2013. We believe that this will provide the financial flexibility to improve operating results and provide sufficient liquidity to meet our obligations for the next 12 months.

Liquidity isn’t the only issue for RadioShack. Since fiscal year-end 2000, RadioShack’s net worth has declined by nearly 92%; declining from $880.3 million, at 12/31/00, down to $72.6 million as of 5/3/14—RadioShack, as a side note, changed its fiscal year-end in 2014. Precarious leverage is also a huge problem for this retailer. As of fiscal year-end 2000, RadioShack’s total-liabilities-to-equity ratio was 1.9 to 1; which was well under the 3 to 1 ratio where investors should start to get nervous. At the close of the most recent quarter, this ratio was over 17 to 1; and part of the aforementioned turnaround plan entails piling more debt onto a highly-leveraged balance sheet. Ouch! The bottom line is RadioShack’s balance sheet is a train wreck.

The following table disproves the claim that RadioShack’s recent losses are the proximate cause of its current financial difficulties. This retailer, since 2000, has turned a profit in twelve of the past fourteen years. From 2000 through 2011, RadioShack generated total profits of nearly $2.7 billion. In 2012 and 2013, RadioShack lost almost $540 million. Losses over the past couple of years, therefore, do not explain RadioShack’s present financial woes. Hence, in order to understand why this company is teetering on insolvency, it is critical to focus on the fact RadioShack has engaged in stupefying stock buybacks in ten of the past fourteen years. Perhaps massive stock market bull runs and miniscule interest rates, over the past fourteen years, have played into management’s decision to aggressively repurchase shares.

Year Net Profit Stock Buybacks

2000 $368.0 $400.6

2001 $166.7 $308.3

2002 $263.4 $329.9

2003 $298.5 $286.2

2004 $337.2 $251.1

2005 $267.0 $625.8

2006 $ 73.4 $0

2007 $236.8 $208.5

2008 $189.4 $111.3

2009 $205.0 $0

2010 $206.1 $398.8

2011 $ 72.2 $113.3

2012 ($139.4) $0

2013 ($400.2) $0

Totals $2,144.1 $3,033.8

To be sure, this table should be embarrassing to RadioShack’s directors and officers. Share repurchases, since 2000, have exceeded net profits by an astonishing $889.7 million. It’s no wonder why this company’s net worth is approaching $0; and, I believe, will soon go negative. Wouldn’t these directors and officers love to have the $3 billion, they spent on stock repurchases, back in the company’s bank account? Wouldn’t an extra $3 billion, of cash, buy management the time it needs to execute its turnaround plan? RadioShack, once again, had been profitable for twelve of the past fourteen years; meaning it did a lot of things right and pleased countless customers. Alas, with a paltry cash position of $61.8 million, as of May 3, 2014, it appears unlikely RadioShack has the liquidity to execute its turnaround plan—even with a credit facility available, I believe its balance sheet is too far gone to avoid bankruptcy. Remind me again of what defines excess cash? How did share repurchases enhance shareholder value?

With the stock market returning to bubble territory, stock buybacks for the Russell 3000 amounted to $567.6 billion in 2013. Share repurchases, in the previous bubble, hit an all-time high of $728.9 billion in 2007; right before the financial crisis of 2008 unfolded. It seems, indeed, as if corporate executives become intoxicated by bull markets in stocks. Can you say “buyback fever”?

For followers of Austrian economics, it is understood that stock market bubbles are fueled by the Federal Reserve’s monetary pumping; which goes hand-in-glove with artificially low interest rates engendered by the Federal Reserve. Consequently, misleading interest rate and price signals can cause businessmen to make costly errors in judgment. Since stock buybacks, misguidedly, are considered investments in one’s own business, are we not witnessing a massive clustering of errors with innumerable executive management teams authorizing malinvestment on a grand scale? Instead of businessmen misreading market signals and malinvesting in capital and producers goods, many are malinvesting in shares of their own companies via stock buybacks. Like RadioShack, over time, will other companies strip-mine equity until their balance sheets become depleted? Once the current Federal Reserve induced bubbles implode, I’m confident RadioShack will not stand alone as to having gone bonkers, and broke, with buybacks.