The juxtaposition of the official unemployment rate in Japan against wage gains (losses, more precisely) raises an interesting and potentially debilitating conundrum. More workers are being employed inside Japan, but the average pay rate clearly is falling for new jobs. This, of course, sounds very familiar to Americans that have seen exactly that process play out in our versions of QE-recovery, but that means the unemployment rate itself in Japan, like the US, isn’t descriptive enough, or hold the correlations that were once assumed to be valid and durable.

The unemployment rate has been declining steadily in Japan since last summer – in August 2013 it was 4.1%; in May 2014 it is now estimated at a low of 3.5%. May’s figure is being used as evidence of Abenomics’ success, attaining what is believed to be full employment. If that is actually the case, then it would seem to indicate that perhaps wages might finally be “forced” upward as slack has disappeared.

While that is a possibility, I suppose, I don’t believe there is much difference between 4.1% and 3.5%, particularly when viewing the Japanese economy as it gets wretched by the consumer price increases the Bank of Japan claims it wants. The primary mover of prices has been imports, which is not exactly following the orthodox script to full economic restart. In fact, that is the opposite of what was supposed to happen, regardless of the unemployment rate.

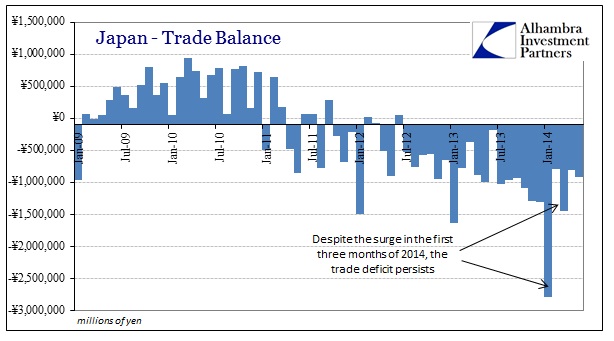

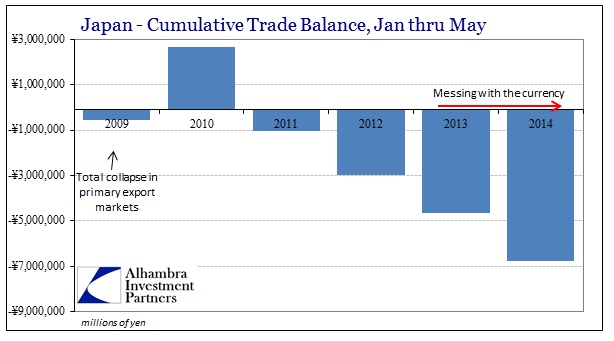

The trade deficit so far this year has been monstrous, with only a small abatement in April and May rather than the sharp snapback expected after January and March.

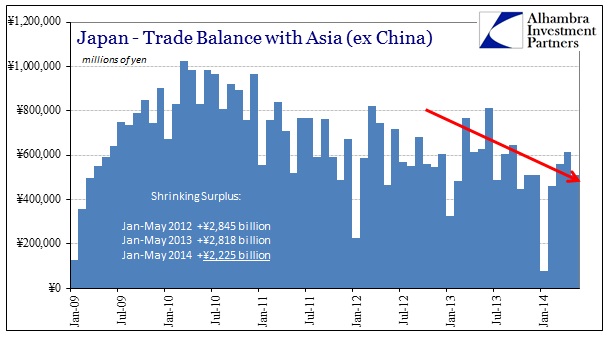

The movement of production to China and elsewhere in Asia has to be the largest and most damning counterforce to yen-manipulation plans. Japanese businesses were expected to increase exports of goods, not to offshore production and then import merchandise back to Japan. But that is clearly what has happened.

That leaves unanswered exactly what kind of jobs are being “created” in Japan to bring the unemployment rate down. They are certainly not the manufacturing jobs that were counted as being the primary “pump priming” of the currency adventure, which more than suggests a bartender and temp economy once again much like the US (at the margins). Maybe that is better than nothing at all, but that is the wrong counterfactual, I believe, to be used a standard.

The gutter of currency intervention has boosted price increases to a level not seen since the early 1990’s. Without the coincident gain in what can fairly be called “breadwinner” jobs, that leaves Japan far worse off, a fact that I think was fairly evident in the spending surge just prior to the tax hike. Spending data in the months since have confirmed as much, as households were undoubtedly draining savings at an incredible pace in order to save just 3% in tax.

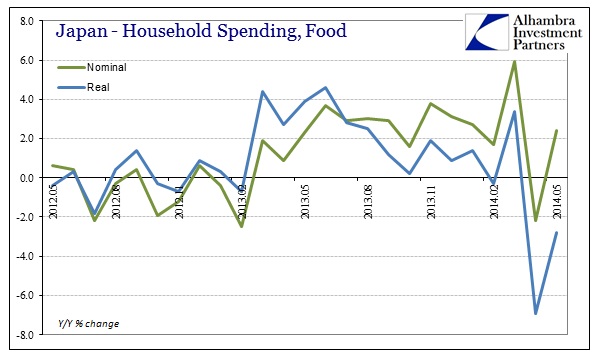

It is clear from the chart above just how much of an impact the new price pressures are having, and not in a positive direction. The poor inundated Japanese are paying more and getting less, which belies the idea of “full employment” and a new healthy economic regime. What it instead suggests is growing bifurcation, one more time like the US, where those with access to asset inflation and Bank of Japan beneficence are doing well enough to redistribute job growth into the lowest paying service sector jobs.

Such concentration is exasperatingly unhealthy, and, more important, unstable (thus the spending data). This is even clearer in terms of sector breakouts, where food spending indicates significant problems. And housing, which has been one of the primary factors driving GDP, finally relented in a big way as the tax “benefit” to consumption is now past.

Maybe it is just me, but I don’t see how producing fewer goods domestically and redistributing those jobs to low-wage retail, while at the same time dramatically increasing the cost of living, is going to foster a durable and healthy recovery. It sounds instead exactly like impoverishment, particularly as the degree to which the Japanese people have to spend a lot more to get less without any proportional offset in systemic wages. Inflation should be measured not as prices compared to past prices, but prices compared to income, particularly earned income.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@alhambrapartners.com